The Indian Army is facing an unprecedented shortage of manpower. In June 2019, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh informed the Rajya Sabha in a written reply that there were 45,634 vacancies in the Army as on January 1, 2019. This included 7,399 vacancies in the officer cadre. Would they be made up in the near future? Unlikely, if we go by past experience.

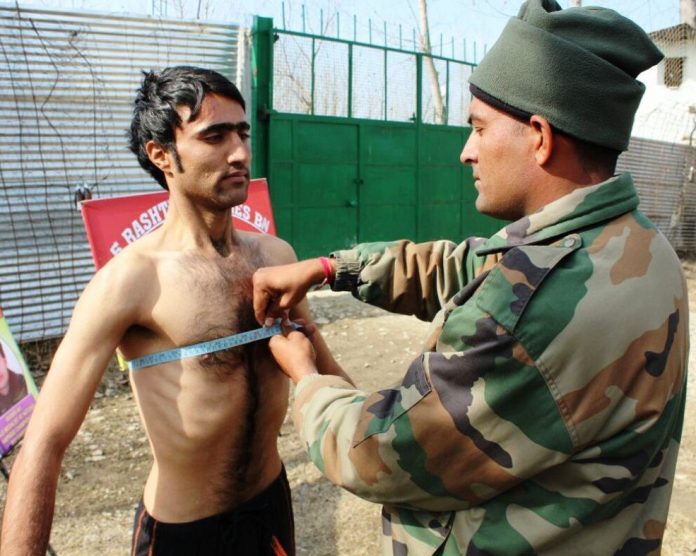

Of course, there has been no dearth of volunteers eager to join the Army at recruiting rallies because joining it is a way of life for many. In rural India, it is still considered an honourable profession. But invariably, most of the youths fail to clear the minimum physical fitness and literacy standards set for various branches of the Army.

There are many reasons for this. The Army has uncompromisingly tough physical fitness and medical standards for recruitment. In the case of officers, there are psychological and leadership aptitude tests in which many fail. Continuous deployment of troops in difficult terrain away from their families for prolonged periods makes it less attractive than a civilian job in an increasingly urbanised setting. Better opportunities for promotion and perks in private undertakings siphon off well-qualified youth from job markets. High achievers are attracted by civilian government jobs which offer better opportunities for quick promotion and perks than offered by the Army.

Manpower deficiencies in the Army are nothing new. It is a hardy, perennial experience in the entire career of many commanding officers. Manpower deficiency is only the tip of the iceberg of problems that the armed forces are trapped in, along with the tangle of political indifference, revamping the national security apparatus and military and civil red tape. Over the years, a number of committees have examined various issues affecting the armed forces. However, implementation of their recommendations had been tardy, subject to lack of the political leadership’s commitment, financial crunch, bureaucratic indifference and the military’s own internal rivalries.

In 2016, Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar constituted an 11-member committee of experts under Lt Gen DB Shekatkar (Retd.) to recommend measures to enhance combat capability while rebalancing defence expenditure of the armed forces. The Shekatkar Committee made 99 recommendations in its report submitted in December 2016. These ranged from optimising the defence budget to the need for a Chief of Defence Staff (CDS). These recommendations, if implemented, could result in saving up to Rs 25,000 crore in defence expenditure over the next five years.

A recent news report that the Army was considering a proposal titled “Tour of Duty” (ToD) to induct young men and women as officers and soldiers for three years on a “trial basis” has to be viewed in the overall context of the Army’s structural reforms undertaken to implement the Shekatkar Committee recommendations. The ToD concept was to tap “resurgence of nationalism and patriotism” among youth who wish to experience military life for a temporary duration rather than taking it up as a profession. The report added the “game changer” proposal was being examined by top commanders and its main aim was to bring people closer to the force by giving them an opportunity to experience military life. “If approved it will be a voluntary engagement and there will be no dilution in selection criteria. Initially, 100 officers and 1,000 men are being considered for recruitment as part of test bedding of the project,” said Col Aman Anand, PRO, Army.

Not unexpectedly, the ToD news report received both brickbats and bouquets from senior veterans. Lt General Raj Kadyan, Deputy Chief of the Army Staff, has been sharply critical of ToD. He said the ToD officer aspirant’s likely pre-commission training period was three to six months as against three and a half years of an NDA cadet or one and a half years’ training given to cadets through the Indian Military Academy (IMA). So ToD officers are “likely to end up at best as semi-trained leaders”. This is not wholly correct.

After the Army’s 1962 debacle, to meet the manpower needs of sudden expansion of the forces, the Army introduced emergency commission (EC). EC officers were given basic training for six months and inducted into the units. I, as an EC officer, was a witness to their stellar performance on the front lines as young officers in both the 1965 and 1971 wars. Many of them sacrificed their lives in these wars. It was no less than that of permanent commissioners.

General Kadyan also said that because of the difference in training period, jawans are unlikely to respect a ToD officer the way they do a normal officer. Their faith and confidence in him and his judgement in times of crisis will be a lot less. It is difficult to accept this argument because ToDs will be exposed to a tough training regimen in their units, which is a unit commander’s responsibility. A modern jawan is smart enough not to be impressed by just labels or pedigree. Thirdly, he said that the attitude and commitment of the ToD officer, a “transient”, will not be the same as that of the normal officer. Of course, it will not be the same, but the ToD has a greater urge “to prove himself” as EC commissioned officers would vouch. This can motivate him to perform better.

Lastly, the General said that the impact of the ToD concept on the Army will be adverse, eroding its professional capabilities. Fortunately, the Army’s professional capabilities are not dependent upon the performance of a handful of ToD officers but on the units and formations as a whole. The Army has a culture of taking things in its stride and turning them into what it needs.

As against these arguments, exposure to the Army’s training, discipline and management skills under difficult conditions would help the ToDs who would later join civilian occupations. This would be a welcome addition to corporate culture and civil society. But yes, the Army has its own internal elitist crony system based on pedigree—military schools, NDA entries, IMA graduates and short service officers. ToD cadres are likely to end at the base of this pecking order. However, performance usually outweighs this system unlike the caste system we are accustomed to which forms an unenviable part of our socio-political culture.

Shorn of such lofty concept, the ToD seems to be yet another aspect of the current cost-cutting exercise that the armed forces has undertaken, while making up manpower deficiencies. According to an analysis in The Print, the cumulative cost for a three-year ToD service officer, including pre-commission training, pay and allowances, is expected to be Rs 80-85 lakh as against Rs 5.12 crore and Rs 6.83 crore, respectively, for an SSC officer after 10 and 14 years of service, respectively.

Already, General Bipin Rawat, CDS, has taken up a number of cost-cutting initiatives like extending the retiring age of armed forces personnel below the rank of officers to 58 and asking the forces to get rid of their overwhelming dependence on exorbitant foreign weapon systems and support “Make in India”. Commenting on the ToD concept, the CDS said it was at a nascent stage and under the Army chief’s consideration. According to the media report, he said, if it works out, it is good, but added that its viability needs to be studied. He reportedly said: “It will require a year of training. The ToD will be in Kashmir and the Northeast…. One year of training cost… equipping him and doing everything for him and then losing him after four years. Is it going to balance out? It will require a study.” This reflects the CDS’s reservations about this concept.

But the core issue in military manpower is only one: will the soldier be able to meet the emerging battlefield expectations of performance? President Abdul Kalam, during his maiden visit to J&K in June 2004, visualised the “future soldier” when he spoke to the troops: “When I see you, I visualise in a few decades that the configuration of the soldier in the planet will undergo a change, with the focus on him carrying a payload with lighter and high performance weapons, high calorie food and intelligent clothing to meet temperature variance and self-contained networked communication system. These features will assist mobility and survivability in the battlefield. Mobility, lethality and survivability will be provided through the integrated helmet, body protection and weapon instrumentation.”

Kalam saw the integrated helmet with a computer system, sensor display, night vision instruments, communication systems, video cameras and image intensifier. Body protection was achieved through smart clothing with ballistic protection, reduced weight, smart shoes and NBC suits with mine sensors. He told the soldiers: “I can imagine that a few years from now, you will have intelligence-gathering apparatus and computer and communication systems being made part of your apparel.”

Kalam’s futuristic vision is no fiction. The Indian Army conceptualised the

F-INSAS (Future Infantry Soldier As a System), a futuristic modernisation plan, between 2007 and 2012. In 2015, due to high costs, it decided to implement it in two components: one to arm the future infantry soldier with the best available assault rifle, carbines and personal equipment such as helmets and bulletproof vests and the second, battlefield management systems. The Indian soldier’s helmet will be made of a lighter-weight composite material so that it balances out the additions of visor, camera and internal communication system, but still protects him from 9mm carbine rounds and shrapnel. It is possible that armoured clothing could include a shear-thickening capability that not only disperses the impact of a gunshot or blast, but potentially harnesses and transfers that energy for its own internal energy system.

There is no end to modernisation as many countries have realised. It is an expensive process as technology and tactics keep it dynamic. Can the Indian Army upgrade the entry level of its soldier to absorb and deliver the requirements of fighting in the modern battlefield? Only the country, not merely the Army, can answer this question.

—The writer is a military intelligence specialist on South Asia, associated with the Chennai Centre for China Studies and the International Law and Strategic Studies Institute

Lead picture: Twitter