The real story is about a bold experiment to see how we can be manipulated and how much disruption people are willing to tolerate.

By Peggy Mohan

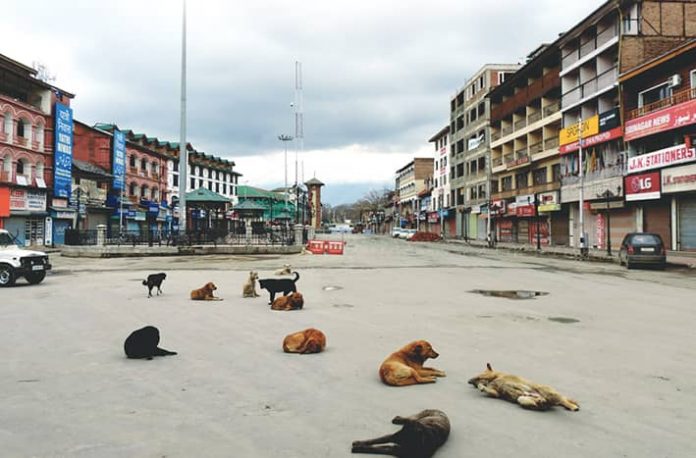

The first and most striking thing we have learnt during this time-outside-of-time is how truly easy it has been to shut down almost all the activity that was heating up this planet, and in the wink of an eye. We were “just a few minutes to midnight” on the clock that marked our transit into irreversible climate change, with no sign of anyone at the top listening, when a massive time-out was called, and the mighty fossil fuel industry sat by meekly watching their ships unable to move, unable to unload, stuck in place on the high seas, with the price of petrol in many countries slipping below zero: they would pay you for relieving them of their petrol. Skies turned blue, rivers ran clear, and animals came out to occupy the spaces that humans had vacated.

The mechanisms of social control also took a step-jump forward in this period. It has always been possible to control people’s behaviour by stoking their fears while depriving them of a basic need. For centuries people’s fear of hell fire in the hereafter kept most of them “chaste”, with the rest of society ready to punish anyone who didn’t buy into the restriction and simply followed their sexual urges. Then in the 1960s with reliable contraception that myth began to crumble, and in its place came a restriction on something even more essential than sex: food. After all, there were too many people who could do without sex, especially people who were older and no longer in the mating game, and timid youngsters with no biological reason not to “be good”. The ideal body type became thinner and thinner, and food became a thing to be suspicious of. The control this brought, particularly over women, was neatly illustrated by a photograph of an anxious female executive with the caption: “$100,000 a year but 1,000 calories a day”: a starvation diet. Large numbers of people lived most of their lives on a diet, in a world where for the first time food was plentiful and easy to buy, unable to let go and simply “eat”.

But there was always something more vital than sex, more vital than food: air. This lockdown saw the start of deep suspicion seeded about the very air we breathe, with people going out into the cleanest air many have seen in their entire lives wearing masks, preferring to breathe in their own exhaled carbon dioxide for fear of inhaling a virus. One saw motorcycle riders going without helmets, but with masks over their noses and mouths, suddenly more alert to the threat from a virus that had a .5 percent chance of being fatal than to the more immediate danger of head injury and death from a traffic accident. There were even reports of runners dying of cardiac arrest because their masks deprived them of the oxygen they needed.

Panic works. People seem to be divided into those who are compliant but sanguine, taking the mandated precautions but going on with their lives, and those who live in a frisson of fear, ready to attack anyone who suggests that our lives are not in dire danger, and showing an almost ghoulish excitement at the thought that if deaths haven’t been happening fast enough in India, that is sure to change soon. It might, but there is no evidence to support that belief, not as yet. Like people with a phobia of spiders, they are glued in place staring at the wall.

Long before herd immunity comes herd behaviour. Those of us who see people as individuals capable of thinking for themselves are, once again, dismayed to see most people falling into predictable roles, like lemmings, or like migratory geese. If the man at the top calls for a lockdown, not only will the police enforce it, as their job demands, but so will the RWAs, the Resident Welfare Associations, who pick up the new gestalt and pass it on, often using their imaginations to take it further. They lock down their localities keeping food deliveries out, keeping people over the age of 60 confined to their homes, looking out of their windows to see who is going out without a mask, and stigmatising patients and even medical workers. There is a point at which a system becomes self-sustaining, because a section of the community is hard-wired to enforce whatever seems to be the “right” thing to do.

Another thing we knew without having to see it so starkly is that it would be the poor who would pay the price for this shutdown. It always is. And that is something that we need to keep in mind if we ever choose to repeat this exercise, either to “save the planet” or for some other reason linked to the further concentration of wealth and power. Much as we knew that the only antidote to an economic model based on relentless extraction and consumption was poverty, where reducing consumption was no longer a matter of choice or of being kind to the planet, we always knew that this poverty would not be distributed evenly. That we were not going to see any sort of levelling, with the billionaires cut down to size so that human society might survive, but a brutal triage where many of the world’s gentler voices would go silent.

There is also an important takeaway, here, about new viruses, and about how best to stay far from them. Viruses have a nasty way of turning up when we disturb the environments they have settled into. When our eternal greed for resources takes us into the bush, where we feed ourselves on bush meat which incorporates viruses to which we are still unadapted. Or when we allow the permafrost, with all its frozen locked in viruses, to melt. We do not need to go ourselves into the bush to release these viruses: even as I sit here typing I am endorsing the spread of these bits of RNA, because the coltan needed to make my cellphone is extracted from deep in the Congo where miners go, and where they must eat to live. The one thing that did not see any shutdown during this period was the internet, making this not a step backward to a more sustainable world, but forward to a strange dystopia where some things have gone missing while others are doing better than ever.

The real story of this lockdown is not about a virus. It is about a bold experiment to see how we can be manipulated, how much disruption people are willing to tolerate, and how much fear it will take to achieve a consensus that it is all for the best. If we have any doubts, all we need to do, in India, is look at how it all started, suddenly, at a time when the virus was just a distant glimmer, and how it is being ended when it is up and running, though mercifully not as lethally as in the West. At a guess, I would say that this period is a sign of a phase change, a shakeout, if you like, where we are set to be more connected than ever even as we sit alone with our phones and computers. And it is this mix of the desirable nested in the undesirable that makes it a time when we must pause, and ponder.

—The writer is a best selling author and lecturer

Lead Picture: UNI