A WHO group has dropped the word “counterfeit” and replaced it with “substandard and falsified” with regard to drugs. This is more in keeping with public health concerns than intellectual property rights

By Nayantara Roy

What’s the difference between substandard, spurious, falsely labeled, falsified, counterfeit (SSFC)—all terms relating to medicine? The World Health Organization (WHO) Member State Mechanism recently decided to simplify this terminology on the basis of recommendations by an informal working group. This included representatives from India, China, Brazil, the US, Argentina, Ireland, Indonesia, Tanzania, Nigeria and Spain. Instead of “counterfeit”, the terms used henceforth will be “substandard and falsified”. This will be placed before the World Health Assembly when it meets in May 2017.

So what’s in a name, one might ask? India is a large manufacturer and exporter of generic medicines. In 2008 and 2009, almost 20 shipments of generic medicines from India to developing countries were detained at customs by European Union authorities while in transit through Europe. They were stopped on the grounds that they may be “counterfeit” medicines, ie medicines that infringe trademark.

CONFUSING TERM

Michael Deats, group leader for the SSFFC Surveillance and Monitoring, Safely and Vigilance, Essential Medicines and Health Products at the WHO told Intellectual Property Watch: “[T]he term ‘counterfeit’ is now usually used in the context of protection of intellectual property rights. Substandard and falsified products are a public health issue and the focus should be firmly on protecting public health.” He also reportedly informed the website that the terms spurious, and falsely labeled were dropped as “falsified includes all variations of deliberate and fraudulent misrepresentation”.

Dr Unni Karunakara, formerly International President of Medicine Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) and currently Senior Fellow, Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, Yale University, explained to India Legal: “The term ‘counterfeit medicine’ is overly broad and creates confusion because it conflates intellectual property issues with public health problems. Different organizations and countries use different definitions of the word, making it hard to know exactly which problem is being referred to when this term is used. Some definitions focus on broad intellectual property terms and so confuse legitimate generic medicines with dangerous fakes. For this reason, MSF believes the term counterfeit should not be used in relation to medicine and instead more accurate and precise terms such as ‘fake’ or ‘substandard’ should be used.”

Dr Unni Karunakara, formerly International President of Medicine Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) and currently Senior Fellow, Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, Yale University, explained to India Legal: “The term ‘counterfeit medicine’ is overly broad and creates confusion because it conflates intellectual property issues with public health problems. Different organizations and countries use different definitions of the word, making it hard to know exactly which problem is being referred to when this term is used. Some definitions focus on broad intellectual property terms and so confuse legitimate generic medicines with dangerous fakes. For this reason, MSF believes the term counterfeit should not be used in relation to medicine and instead more accurate and precise terms such as ‘fake’ or ‘substandard’ should be used.”

He also explained that “a generic medicine is a legitimately produced medicine that is an exact copy of the originator product and performs in exactly the same way. Generic medicines used in donor-funded treatment programs and by MSF must meet quality standards to prove they are just as effective as the originator product. Health programs around the world rely on these affordable copycat medicines.

“A substandard medicine is a drug that does not meet quality standards—it may contain too much or too little of the active ingredient, may be contaminated, may be poorly packaged or fail to meet quality standards in other ways. These medicines may be legitimately produced mistakes or may have been knowingly produced to a substandard level. Both originator and generic medicines can be found to be substandard, and the issue of substandard medicines is a neglected one that needs far more attention.

“A fake medicine is deliberately and fraudulently mislabeled, giving false information on where it was made or by whom so that people will think it is a legitimate medicine. Fake medicines are dangerous as they are unlikely to contain the active pharmaceutical ingredient needed to make the medicine effective, and may even contain harmful substances. They present a serious threat to public health that needs to be appropriately addressed.”

NEFARIOUS MEANS

In addition to “counterfeit” meaning deliberately fraudulent products being passed off as the real thing, Karunakara said it could also be applicable when a company repackages and sells expired medicine with a fresh expiry date printed on the new packaging. This was recently done in Kenya.

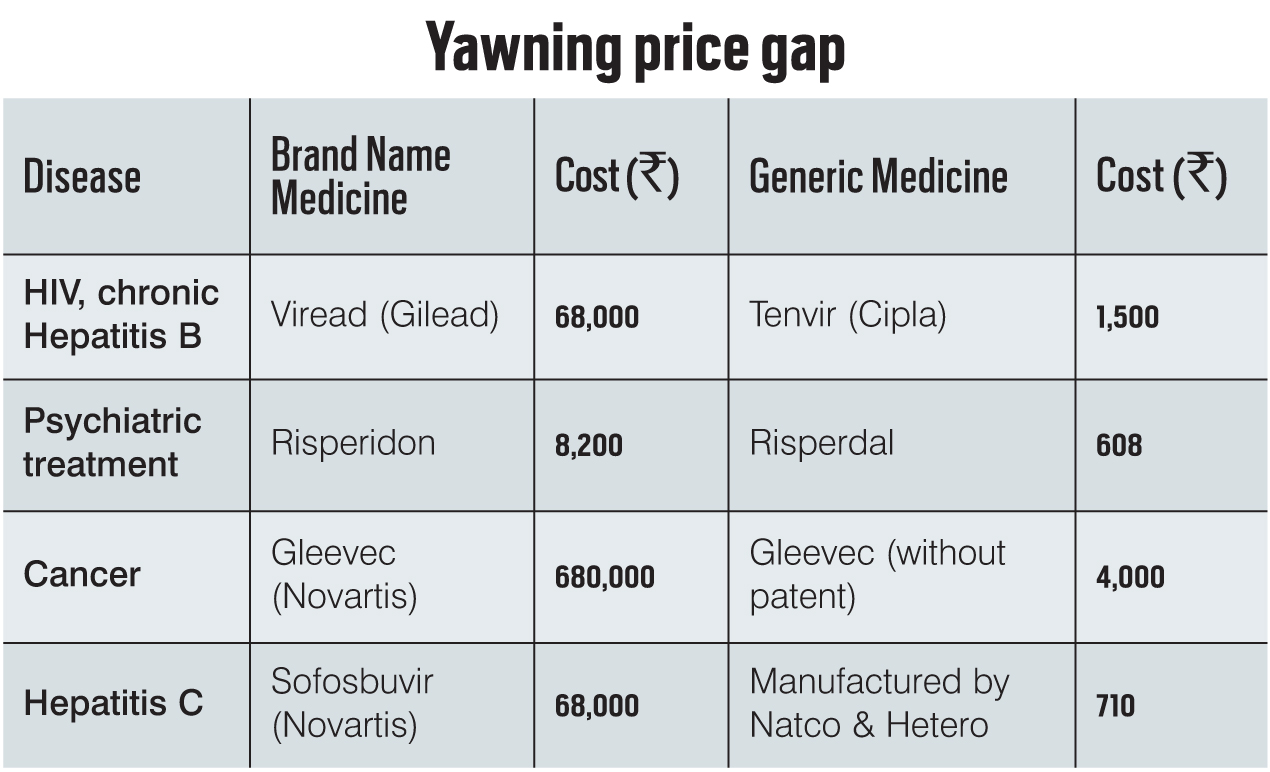

Generic medicines, on the other hand, are legal copies of an original product and for a variety of reasons, are usually much cheaper to produce. Karunakara gives the example of how the cost of retroviral medicines for AIDS in 1999-2000 was about $10,500 per year per patient. Cipla’s Yusuf Hamied said that he would make medicine costing $1 per day, around $360 per year per AIDS patient.

While “counterfeit” means deliberately fraudulent products being passed off as the real thing, generic medicines are legal copies of an original product and for a variety of reasons, are much cheaper to produce. India is a large manufacturer of generic medicines.

Generics also help in keeping the prices of medicines down, which can be inflated by patent holders in a practice termed “price gouging”. This was illustrated vividly in the case of Martin Shkreli, CEO and founder of Turing Pharmaceuticals, who acquired a license to manufacture the anti-parasitic medicine, Daraprim. He reportedly raised its price from $13.50 to $750. Daraprim is used for treatment of people with “compromised” immune systems. Shkreli reportedly defended his action by citing the high cost of marketing and distribution.

This also brings to mind the case of a group of pharmaceutical companies (many of them multinationals) which attempted to sue the South African government in 1998 for making changes to the law which would have helped people get access to cheaper AIDS and other medication. The companies alleged that South Africa’s amended Section 15C of the Medicines and Related Substances Control Act (allowing parallel imports of patented medicines) was in violation of both the South African constitution and the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). The amendments also contained provisions for generic substitutions of “off-patent” (i.e. where the patent has expired so the formula is now in the public domain) medicines and transparent pricing of medicines.

The government argued that the amendments were neither in violation of the South African constitution nor of TRIPS. In fact, some of the changes had been drafted with help from the World Intellectual Property Organization.

The flexibilities within TRIPS were further clarified later in the Doha Declaration (the Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, WTO Ministerial 2001). But in the interim, the US had withheld trade benefits and had even laid out the threat of sanctions against South Africa. However, there were large-scale public demonstrations in the US as well as in Europe against the action of the pharmaceutical manufacturers, which forced the US government to reconsider its actions. Due to the strong public reaction, the case was withdrawn.

SUBSTANDARD DRUG

In India, the case of Novartis vs Union of India made a bit of stir when the Supreme Court upheld the denial of patent to Novartis for its anti-cancer drug Gleevec. Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970 has stringent requirements for patenting and it was found that Gleevec did not fit the standards required to be given a patent in India.

Generic medicines can be manufactured legally in three ways. One is when the patent term expires and the process and product come into the public domain. Another is to get a license from the patent owner who then gets royalties and the third is “compulsory licensing”, i.e., when a government adjudges that there is a public health crisis in the country and it gets a compulsory license to manufacture the patented medicine. In the past, the US and Brazil have had issues over compulsory licensing policies followed by Brazil.

When Rahul Chadha, CEO and Whole-time Director at RWL Healthworld Ltd. (which operates businesses and retail products under the brand names Fortis Healthworld, Wellness Tree and Medsource) was asked about the possible effect that removal of the term “counterfeit” would have on the Indian generics industry, he said: “WHO’s stand on dropping the usage of the term counterfeit in lieu of falsified is a matter of semantics…it does not address the issue of big pharma fighting to save its turf from generic manufactures… till such time as medicine is big business such commercial tussles between corporates, countries and trade blocs will continue…”

The change in nomenclature is, therefore, more to do with making sure that “bad” medicine does not get into the market and that agencies do not waste their time stopping the sales of perfectly usable medicine. As Karunakara said, governments (including India) need to develop the capacity to stop “bad” medicine from reaching people.

Access to medicine is an issue that is fraught. The contentious point is whether it should be viewed from a largely commercial point of view or by balancing commerce with need. In the meanwhile, governments need to improve their capacity to fight criminals who have no compunction about selling spurious or substandard material to the sick.

Lead Illustration: Amitava Sen