The 60-page note of the former Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister has created a sensation in legal and political circles. But does it offer enough evidence to pass the legal litmus test?

~By Ajith Pillai with Bureau Reports

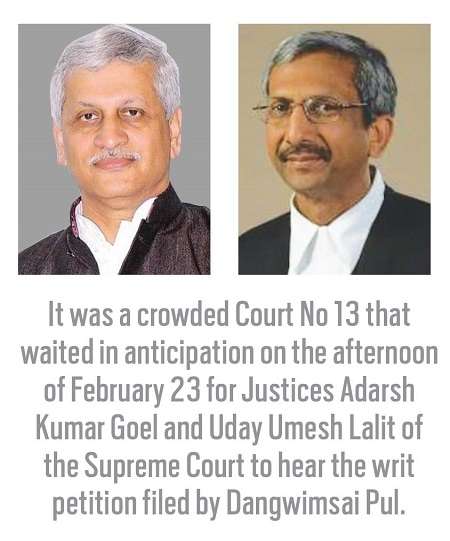

Anti-climax! That succinctly sums up the tame end of Part I of the “Kalikho Pul Suicide Note” saga. It was a crowded Court No 13 that waited in anticipation on the afternoon of February 23 for Justices Adarsh Kumar Goel and Uday Umesh Lalit of the Supreme Court to take up Item No 61 on the cause list. The matter before the two judges dealt with a letter addressed to the Chief Justice of India (CJI), Justice JS Khehar, by Dangwimsai Pul, the widow of former Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Kalikho Pul, who committed suicide on August 9 last year.

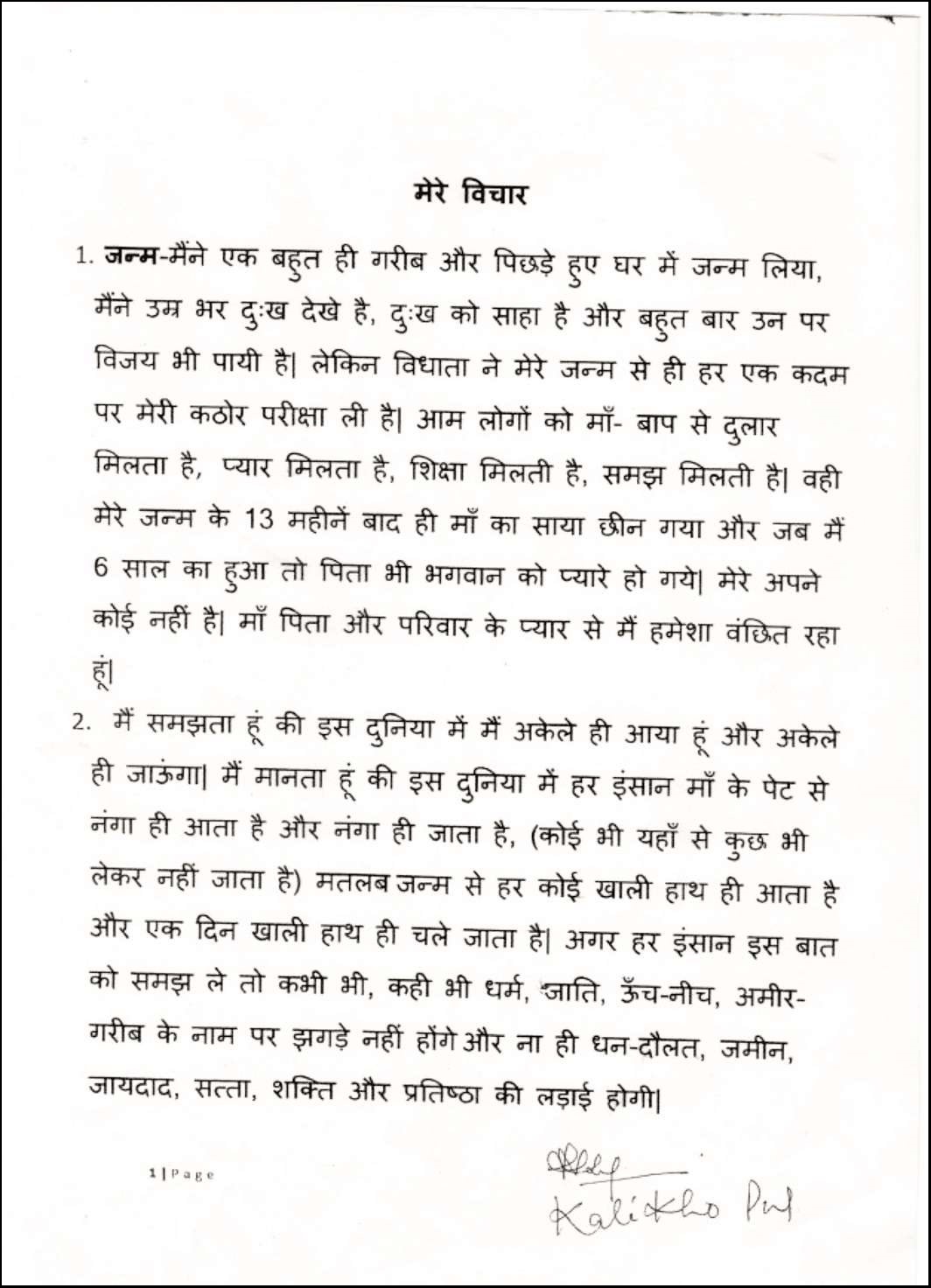

Before he ended his life, Pul left behind a sensational 60-page diary strangely titled Mere Vichar (My Thoughts), in which he levelled serious charges of corruption and bribery against ministers from his state, senior politicians in Delhi and relatives of sitting and former judges of the Supreme Court. It spared no one, including the highest levels of the judiciary, and the President.

Pul lost his chief ministership when his five-month old government was dismissed by the Supreme Court in July 2016. The following month he committed suicide.

The deceased chief minister’s widow had written to the CJI on February 17, seeking directions to register an FIR based on the allegations in the suicide note. The case was suddenly listed for hearing and Dangwimsai Pul’s letter was taken up as a writ petition. Dangwimsai expected the Supreme Court to either hand over the case to the CBI or set up an SIT to probe the allegations.

But that was not to be. Her counsel, Dushyant Dave, concluded proceedings rather quickly by withdrawing her prayer before the court. It was subsequently “dismissed as withdrawn.” Dave cited reasons why his client was forced to make such a move (see box). Dangwimsai Pul will have to take her fight elsewhere. She told India Legal that she will “soon be petitioning the Vice-President” since the suicide note also alludes to the President.

While Dangwimsai’s plea in its present form is a closed chapter, the focus still remains on the curious “suicide note” that surfaced almost six months after Kalikho Pul’s death. Several question marks hover over the note. Were the allegations all true? Was it backed by an evidence? Was Pul actually approached by middlemen (in some instances the kith and kin of apex court judges) who were acting on behalf of the honourable judges? When did he write the 60-page suicide note? Was it handwritten or had he got it typed and then signed it? (The copies doing the rounds of the media are typed in Hindi and have his signature at the bottom of every page.)

Plea Withdrawn

Why did lawyer Dushyant Dave counsel his client Dangwimsai Pul, the wife of former Arunachal Pradesh chief minister Kalikho Pul, to withdraw the letter she had written to the Chief Justice of India JS Khehar?

She had sought the CJI’s instructions to file an FIR based on the allegations of corruption against several sitting judges of the apex court made in a suicide note left behind by her deceased husband.

Dave’s reasoning was this:

- The plea should have come up only on the administrative side and not taken up before a judicial bench in an open court as a writ petition. He felt that if the bench heard the petition and dismissed it, then all alternate options would be closed for the petitioner. He had therefore advised his client to withdraw her letter.

- Dave cited that there was conflict of interest involved vis-à-vis a judge on the bench. Justice Goel was a colleague of a judge in a state HC, whose name also figures in the allegations made in Pul’s suicide note.

- He quoted the K Veerasamy judgment to point out that the matter should have been heard by five judges, not two.

The apex court registry’s explanation for listing the case before a judicial bench was that a registration of an FIR could not be facilitated by an administrative order and could be done only through a judicial order.

When contacted by India Legal, Dangwimsai was measured in her words: “This is a legal matter on which I cannot speak much. But I withdrew my petition because I sought intervention on the adminis-trative side but the matter came up before a bench.”

However, sources say she may have decided to withdraw her petition lest she and a middleman, Shyam Arora, who allegedly had regular financial dealings with Kalikho Pul, be exposed for these shady deals running into thousands of crores. Arora, a Delhi businessman, is untraceable, though Dangwimsai has been trying to get in touch with him.

India Legal tried to make some sense of the curious case of Pul’s “suicide note”. Here are some pointers:

- The so-called “suicide note” was written much before Pul’s eventual death. India Legal has learnt from those who knew the former chief minister that he maintained a diary and had been planning a book even before he became CM. He had two diaries—one in which he wrote his “good thoughts” and one in which he penned his selected exposes about corruption and bribery both in Arunachal Pradesh and in the corridors of power in Delhi. So, it was not a “suicide note” written just before he ended his life. It was a preplanned exercise.

A lawyer who knew him closely had this to say. “He often told me about the diaries. He said he was writing things that would create a sensation. He also talked several times about committing suicide but I dismissed it as loose talk. The diaries were handwritten and written over many months. He never typed himself so he has obviously got it typed by someone.” According to him the original handwritten diaries are with his first wife Dangwimsai. (Pul, who was 47 when he ended his life had married three times. Entering into multiple marriages is not unusual in several tribal communities in the North-east).

- Though he denies having seen any handwritten suicide note, Jyoti Prasad Rajkhowa, who was Governor of Arunachal Pradesh when Pul committed suicide, was aware of the typed version of the diary (see interview).

In fact, he was the first to bring the suicide note to light in September last year. It is alleged that he may have done so to rattle the higher judiciary which had come down sharply on his gubernatorial interventions into Arunachal politics which led to Pul, a Congress rebel, becoming CM with the support of BJP MLAs. His actions were dismissed by the court as “unconstitutional” and the Pul government was dismissed.

In fact, he was the first to bring the suicide note to light in September last year. It is alleged that he may have done so to rattle the higher judiciary which had come down sharply on his gubernatorial interventions into Arunachal politics which led to Pul, a Congress rebel, becoming CM with the support of BJP MLAs. His actions were dismissed by the court as “unconstitutional” and the Pul government was dismissed.

- Pul’s interactions with middlemen and those who claimed to peddle influence in Delhi were after he was sworn in as CM on February 19 2016. His appointment was first challenged in the Gauhati High Court by the ousted chief minister Nabam Tuki and the Congress party. The case later moved to the SC.

- It is reliably learnt that Pul operated through several point persons in Delhi-—a senior Congress leader, now largely out of active politics, and a former law minister, and Shyam Arora and Prashant Tewari, both businessmen, once said to be linked to Congress leaders.

- According to a source, Pul may well have paid money to some fixers as he has claimed in his “suicide note.” But the key question is whether those who took crores from him actually paid money to SC judges and constitutional functionaries as they promised.

- So far there is no evidence to prove any financial transactions did take place. But one thing is clear—the fixers failed to get any judgements in favour of Pul. Which brings us to another crucial point. Was Pul taken down the garden path by influence peddlers who milked him of his money? A lawyer in the know had this to say to India Legal: “One is not saying that there is no corruption in the higher judiciary. But there are enough people around who claim they can fix judgements when they actually can’t. Their logic is that if someone is willing to part with money why not take it.”

- Most politicians will tell you in private that politics in the North-east is run on corruption money like nowhere else in the country. Money has to be pumped in to ensure the support of MLAs, to get tickets and votes. Pul won five consecutive assembly elections—in 1995, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014—on a Congress ticket. According to sources, after the 2014 elections he was unhappy with the low-profile health and family welfare portfolio allocated to him when he had already served as the finance minister. That was when he started toying with the idea of toppling CM Nabam Tuki. He sent feelers to BJP organisational leaders willing to support him. But to seal the support of rebel Congressmen and BJP MLAs, money had to be invested. It is believed that hundreds of crores were spent on the CM project and a chunk of it was paid to a BJP functionary in Delhi with strong RSS links.

Complex Procedures Involved

Can a suicide note be an evidence and can allegations in it against sitting apex court judges be investigated? To proceed against a judge isn’t easy because judges are left to decide their own case

Suicide notes, and their content, are different from dying declarations. Dying declarations enjoy a unique status. It is based on the maxim Nemo moriturus praesumitur mentire, i.e. a man will not meet his maker with a lie in his mouth. Since the situation when a man is on his death bed is so solemn and serene, that is the reason in law to accept in veracity his statement, even dispensing with the requirements of oath and cross-examination. As such, dying declaration is taken a lot more seriously than suicide notes. Suicide notes can be taken as evidence in Court, but not as conclusive evidence.

One issue with suicide notes is that they need to be authenticated. Courts need proof that the note was not written by someone else—the handwriting must be authenticated.

The question which arises is, can a suicide note be termed to be a valid dying declaration for the police/investigating authorities to act upon. The element of admissibility of such a dying declaration was considered by the Supreme Court of India in Sharad Birdhi Chand Sarda vs. State Of Maharashtra.

LEGAL POSITION

The relevant provision in law is Section 32(1) in The Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

It states:

“When it relates to cause of death—When the statement is made by a person as to the cause of his death, or as to any of the circumstances of the transaction which resulted in his death, in cases in which the cause of that person’s death comes into question. Such statements are relevant whether the person who made them was or was not, at the time when they were made, under expectation of death, and whatever may be the nature of the proceeding in which the cause of his death comes into question.”

From a review of the various authorities of the Courts and the clear language of Section 32(1) of the Evidence Act, the following propositions emerge:

Whether the cause of the death of the person making the statement comes into question in the case? The expression “any of the circumstances of the transaction which resulted in his death” is wider in scope than the expression “the cause of his death”; in other words, Clause (1) of Section 32 refers to two kinds of statements: (1) statement made by a person as to the cause of his death, and (2) the statement made by a person as to any of the circumstances of the transaction which resulted in his death. The words, “resulted in his death” do not mean “caused his death.”

Thus it is well settled that declarations are admissible only in so far as they point directly to the fact constituting the res gestae of the homicide; that is to say, to the act of killing and to the circumstances immediately attendant thereon, like threats and difficulties, acts, declarations and incidents, which constitute or accompany and explain the fact or transaction in issue.

Section 32 is an exception to the rule of hearsay and makes admissible the statement of a person who dies. Whether the death is a homicide or a suicide, provided the statement relates to the cause of death, or relates to circumstances leading to the death.

In this respect, Indian Evidence Act, in view of the peculiar conditions of our society and the diverse nature and character of our people, has thought it necessary to widen the sphere of Section 32 to avoid injustice.

The first step to resolving anything involving a suicide note requires someone to lodge a first information report (FIR). In the Kalikho Pul case, the allegations are on the Supreme Court’s judges and other prominent political and public figures.

ACTION AGAINST SITTING JUDGES

Can an FIR be lodged against incumbent judges and the procedure to be followed in case of serious allegations against the incumbent Judges? In K Veeraswami vs. UoI [1991SCC(3)655], the Supreme Court, while considering the question regarding the applicability of the provisions of the 1947 Act to judges of superior courts, has held that judges of superior courts fall within the purview of the said Act and that the President is the authority competent to grant sanction for their prosecution.

But keeping in view the need for preserving the independence of the judiciary and the fact that the Chief Justice of India, being the head of the judiciary, is primarily concerned with the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary, the Court has directed that the Chief Justice of India should be consulted at the stage of examining the question of granting sanction for prosecution.

The judgment further said that if the allegations are against the Chief Justice, then the permission required would be of other judges, which would obviously mean the next-most senior judge available.

In the administrative side, the Supreme Court, by a full Court meeting held on December 15 1999, adopted the Report of the Committee consisting of Justice SC Agrawal, Justice AS Anand, Justice SP Bharucha, Justice PS Mishra and Justice DP Mohapatra for the “In-House Pro-cedure” to be followed to take suitable remedial action against judges, who, by their acts or omission or commission, do not follow universally accepted values of judicial life. As per the report, if a complaint is received against a judge of the Supreme Court and the CJI, after examining it, finds the complaint is of a serious nature involving misconduct or impropriety, he shall ask for the response thereto of the judge concerned.

And after his response if he finds that the matter needs a deeper probe, he would constitute a committee consisting of three judges of the Supreme Court to hold an inquiry. If the committee finds that there is substance in the allegations then the CJI shall either advise the judge concerned to resign and if he refuses to resign, he may intimate the President of India and Prime Minister to initiate proceedings of removal.

The Constitution of India, under Article 124 (4), holds that “A Judge of the Supreme Court shall not be removed from his office except by an order of the President passed after an address by each House of Parliament supported by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two thirds of the members of that House present and voting has been presented to the President in the same session for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity.”

The procedure followed to proceed against incumbent judges is a complex one. And judges are left to decide their own case.

—By Mary Mitzy and Aditya Kr Singh

Where did Pul, who claimed he comes from a humble background, acquire all that wealth? Also, if he indeed paid crores to fixers and relatives of SC judges as he has alleged in his suicide note, where did he source all those funds from?

Perhaps some clarity will emerge if the middlemen mentioned in the suicide note are questioned. But will their testimonies, unless backed by incontrovertible evidence, prove anything? It remains to be seen if the suicide note will pass the legal litmus test.

The government, India Legal has learnt, is not inclined to move in the matter that could cause much institutional harm to the judiciary. Also, the home ministry is not convinced that the suicide note is a credible enough document. So as things stand, its curtains for now.