A landmark law alone cannot bring about a shift in attitude towards women employees, but it can ensure that the guilty don’t enjoy impunity, provided the victim doggedly pursues the case

~By Venkatasubramanian

Three recent reports in the media brought into the focus the potential of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, and how it ensures that perpetrators do not enjoy any impunity. But ironically enough, the three instances have also raised questions about the effectiveness of the law in preventing harassment in the first place. Perhaps its deterrent effect may kick in after many others who commit such crimes are booked under the law.

At the moment, only high-profile cases have come to light, although sexual harassment at the work place is known to involve a large number of lower-rung employees as well. Studies in the West have found evidence that supervisors use harassment as an equaliser against women in power. Therefore, whether laws alone are enough to mitigate a social menace like sexual harassment will continue to be debated.

WEBS OF HARASSMENT

Last fortnight, Suparn Pandey, co-founder of news portal ScoopWhoop, was accused by a former employee of sexually harassing her. The website’s other co-founders, Sattvik Mishra and Sriparna Tikekar, were accused of abetting the harassment. The company was also accused of leaking the identity of the complainant in its internal emails, thus violating Section 228A of the IPC.

Under this provision, whoever prints or publishes the name or any matter which may reveal the identity of any person subjected to sexual harassment or violence shall be punished. This could be imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years; the culprit shall also be liable to a fine.

The provision, however, exempts cases where the victim has given her consent to make her identity public—in writing—or cases where the victim is dead, a minor or of unsound mind when her next of kin could give such authorisation. It is alleged that the management of ScoopWhoop was guilty of violating this law.

In March, the CEO of entertainment website The Viral Fever (TVF), Arunabh Kumar, was arrested and later granted anticipatory bail by the Dindoshi Sessions Court, Mumbai. Cases of sexual harassment had been registered against him. As several former women employees of the portal complained of sexual intimidation by Kumar during their employment with the company, TVF denied the allegations, and vowed to bring the authors of the articles or blog posts insinuating such harassment, to justice.

Advocate Rizwan Siddiqui filed a third party complaint against Kumar because he claimed the women complainants are reluctant to set the law into motion for fear of inviting stigma, social isolation, loss of their reputation and procedural hassles.

STRINGENT PENALTY

In both cases, pressure is being brought upon the complainants to withdraw their cases. This is typical of most sexual harassment cases where powerful or influential persons are the guilty and the victim is not of equal status. The big question then is whether the complainant can doggedly fight the case despite having the backing of a very strong law. The jury is still out on that, although there have been cases where strong orders have been passed.

For example, in January, the labour department of the Karnataka government imposed a monthly penalty of Rs 50,000 for five years on a senior manager of a software company, who is facing charges of sexual harassment. The department also directed the company not to promote him or give him any increment for the next three years. The additional labour commissioner, who is the appellate authority, held the company also responsible for the violation, and asked it to pay monetary compensation to the woman.

The complainant, who was an employee of IP Infusion Software India Private Limited in Mahadevapura, a suburb of Bengaluru, alleged that Bharat Chandrashekhar, senior manager (HR) sexually harassed her while she was in service. She appealed to the labour department after the company’s internal complaints committee quashed her petition.

In his December 27, 2016, order, T Srinivas, additional labour commissioner, directed the company to hold back Chandrashekhar’s annual increment and other monetary benefits for three years from January 1, 2017. He directed the company to deduct Rs 50,000 from Chandrashekhar’s salary every month for 60 months, and pay the same to the complainant. He also ruled that in case Chandrashekhar leaves the company, then the amount should be deducted from the money payable to him by the company and the same should be paid to the complainant. And if the company failed to do so, then it would have to pay the amount to the petitioner from its own funds.

The appellate authority further ruled that under the provisions of Prevention of Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act 2013, the company management has to pay the complainant her monthly salary of Rs 30,000 for 16 months (between September 2015 when she was relieved of her duties and December 2016), which came to a total of Rs 4,80,000.

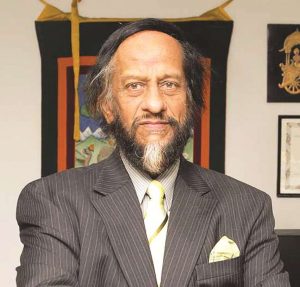

Another recent high-profile instance of sexual harassment involved RK Pachauri of The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2015, the Delhi Police filed an FIR against him on allegations of sexual harassment, stalking and criminal intimidation. The Delhi High Court granted him anticipatory bail. The internal complaints committee of TERI later found him guilty and the institute severed all connections with him. But the fact that prior to that he was allowed to continue holding a position of power in the organisation for a year even as investigations were on meant he was in a position to influence witnesses. Two years since the complaint was filed, the case is nowhere near closure.

LANDMARK LAW

The coming into effect of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, was a landmark. The Act retains the essence of the Vishaka Committee Guidelines laid down by the Supreme Court and expands on its provisions. It widens the definition of “aggrieved woman” to include all women, irrespective of age and employment status, and it covers clients, customers and domestic workers. It expands “workplace” beyond traditional offices to include all kinds of organisations across sectors, even non-traditional work places like telecommuting and places visited by employees for work.

The Act mandates the constitution of internal complaints committees (ICCs), and the filing of an audit report on the number of complaints and action taken at the end of the year. The employer is expected to organise regular workshops and awareness programmes to educate employees about the Act, and conduct orientation ones for the members of the ICC.

If the employer fails to constitute an ICC, or does not abide by any other provision, the Act envisages a fine of up to Rs 50,000. The fine is doubled for repeat offences. If the employer has been previously convicted of an offence under the Act, he shall be convicted for twice the punishment, and the second offence can also lead to cancellation or non-renewal of his licence.

The legal regime for combating sexual harassment at the work place is aimed at exploding the dichotomy between the private realm and public one as far as sexual behaviour is concerned. A law prohibiting sexual harassment is an effort to militate against a mindset that does not shun wrongful sexual behaviour, bias, prejudice and unequal treatment of women at the work place.

A paradigm shift in workplace culture, practices and gender attitudes will take time. Such a shift would require employers to be pro-active and prevent sexual harassment at the work place by pursuing sound principles of corporate governance.

The 2013 Act has certainly created awareness among victims of sexual harassment and explains why there has been a rise in such complaints getting public notice. But the fact that the recent complaints, which have drawn public attention, are high-profile cases, shows that there must be many other cases where complainants who are vulnerable do not pursue their grievances.