The turf war between the judiciary and the executive over appointment of judges reaches another cul-de-sac. There are no signs of a modified Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) heralding transparency seeing the light of day

~By Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

There is a constitutional battle being fought between the BJP-led NDA government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Supreme Court with regard to the appointment of judges to the higher judiciary, namely the high courts and the Supreme Court. The Modi government brought in the 99th Constitution Amendment Act and the National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC) Act in 2014. The idea of the NJAC did not originate with the NDA. It was mooted during the second term of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government and a parliamentary standing committee made a detailed recommendation. But UPA2 could not push through the legislation for setting up the NJAC.

The NJAC was meant to take away the exclusive privilege enjoyed by the Supreme Court to nominate judges through what has become the collegium, comprising the Chief Justice of India (CJI) and four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court. The NJAC, on the other hand, would have included the law minister, two eminent jurists apart from the CJI and two other senior judges of the apex court.

The NJAC Act and the Constitution Amendment that went with it were challenged by the Advocates-on-Record. And the Supreme Court had in its judgment of October 15, 2015 struck both of them down, holding them null and void, and unconstitutional. When the five-judge constitutional bench headed by then Justice JS Khehar was hearing the case, it was argued by the government as well as those who opposed the NJAC, that there is need for improving the collegium system, and that there is need for greater transparency. In the judgment quashing the NJAC, the court had agreed to hear separately suggestions for improving the working of the collegium.

NEW CRITERIA DRAWN UP

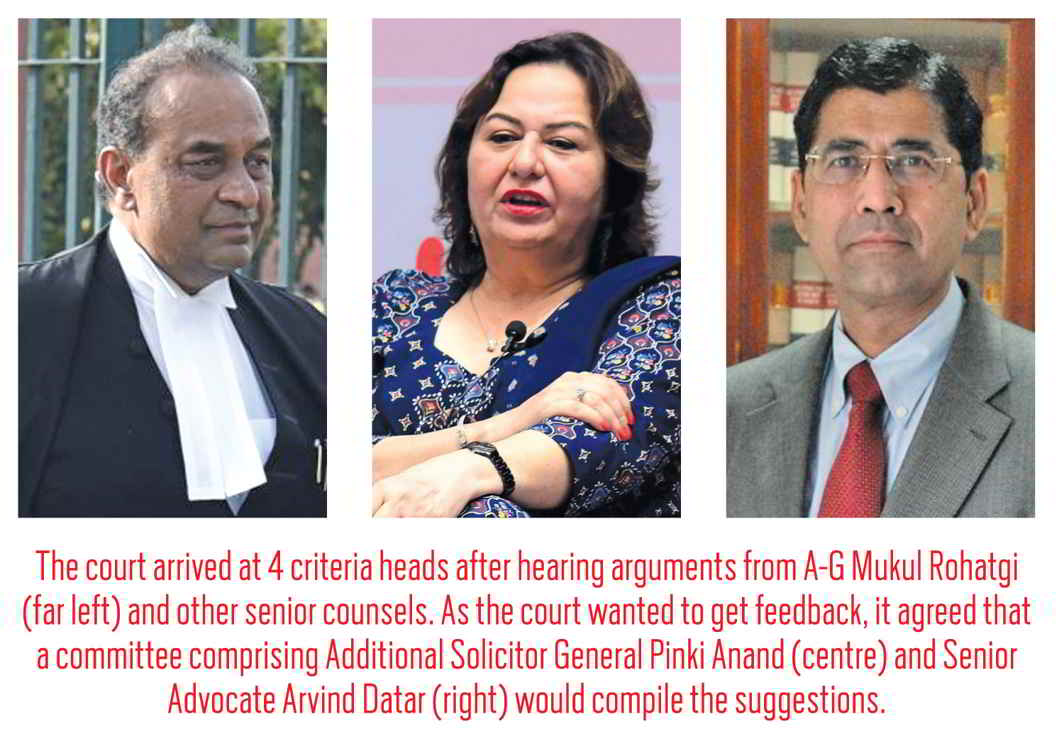

It was in response to this demand that the same constitutional bench heard arguments in November 2015, and it issued an order on December 16, 2015 setting out some of the criteria that could be included in the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP). The order mentioned four of them: Eligibility criteria; Transparency; Secretariat; Complaints; and Miscellany.

The court arrived at these four heads after hearing arguments from Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi and other senior counsels including those from other high courts, and from the Supreme Court Bar Association. As the court wanted to get a wider feedback, it had agreed that a committee comprising Additional Solicitor General Pinki Anand and Senior Advocate Arvind Datar would compile all the suggestions. Most of the suggestions were sent to the website of the Department of Justice, and Anand and Datar brought them under 32 broad heads after sifting through 11,500 pages of them.

A Consultative Process

The working of the presidium as spelt out in what is called the Second Judges case of 1993:

- The process of appointment of Judges to the Supreme Court and the High Courts is an integrated “participatory consultative process” for selecting the most suitable persons available for appointment; and all the constitutional functionaries must perform this duty collectively with a view primarily to reach an agreed decision, subserving the constitutional purpose, so that the occasion of primacy does not arise.

- Initiation of the proposal for appointment in the case of the Supreme Court must be by the Chief Justice of India, and in the case of a High Court by the Chief Justice of that High Court; and for transfer of a Judge/Chief Justice of a High Court, the proposal has to be initiated by the Chief Justice of India. This is the manner in which proposals for appointments to the Supreme Court and the High Courts as well as for the transfers of Judges/Chief Justices of the High Courts must invariably be made.

- In the event of conflicting opinions by the constitutional functionaries, the opinion of the judiciary “symbolised by the view of the Chief Justice of India”, and formed in the manner indicated, has primacy.

- No appointment of any Judge to the Supreme Court or any High Court can be made, unless it is in conformity with the opinion of the Chief Justice of India.

- In exceptional cases alone, for stated strong cogent reasons, disclosed to the Chief Justice of India, indicating that the recommendee is not suitable for appointment, that appointment recommended by the Chief Justice of India may not be made. However, if the stated reasons are not accepted by the Chief Justice of India and the other Judges of the Supreme Court who have been consulted in the matter, on reiteration of the recommendation by the Chief Justice of India, the appointment should be made as a healthy convention.

- The opinion of the Chief Justice of India has not mere primacy, but is determinative in the matter of transfers of High Court judges/Chief Justices.

- In making all appointments and transfers, the norms indicated must be followed. However, the same do not confer any justiciable right in any one.

- Only limited judicial review on the grounds specified earlier is available in matters of appointments and transfers.

The five-judge bench headed by Khehar in its order of December 16, 2015 had asked the government to prepare the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP). While it listed the broad headings mentioned above which could be incorporated, it made it clear that the new MoP should be in conformity with the system of choosing the judges of the Supreme Court and the high courts as it had been spelt out in two of the earlier judgments of the court, known as the Second Judges case of 1993 and the Third Judges case of 1998.

The final version of the MoP puts the government in a tight spot because the court rejected all the major changes that were suggested.

These two judgments set out the process, where the CJI, in consultation with four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, will recommend names for appointment as judges of the Supreme Court, and the CJI in consultation with the Chief Justice of the particular High Court will recommend names for appointment as judges of that High Court. The Supreme Court grouping of the CJI and the four senior-most judges came to be known as the collegium. In the case of the high courts, the chief justice along with two senior-most judges constituted the collegium.

Following the court’s order, government prepared the draft MoP incorporating the new criteria and sent it to the CJI on March 22, 2016. The court sent back the draft MoP in the summer (May-July) of 2016. The government then sent a revised version of the MoP on August 3, 2016. The court returned the MoP in March, 2017 and let it be known that this was the final version in the eyes of the court.

The final version put the government in a tight spot because the court rejected all the major changes that were suggested with regard to wider consultation in choosing judges, transparency on the decisions of the collegium and the need for setting up a secretariat to look at the complaints that came up against those nominated to be judges.

GOVERNMENT DILEMMA

An official in the Ministry of Law and Justice succinctly expressed the dilemma of the government in the face of the MoP that has come back from the court: “The government is not in a mood to confront and it is not in a mood to yield.” Preparing a MoP which would not include major changes would mean that it is back to the old ways of the collegium deciding the appointment of judges of the Supreme Court and high courts through undisclosed consultations among brother-judges.

After having failed to get through its proposal of the NJAC, the government had hoped that it could change significantly the contours of the functioning of the collegium. What was considered a closed-door process was sought to be made more open. But the court is in no mood to oblige. The government is in the unenviable position of not being able to push through the modified MoP and unwilling to accept the status quo.

When the Supreme Court Collegium (SCC) recently cleared the names of 51 candidates to be appointed judges of high courts, it seemed that there was a thaw between the Supreme Court and the government, and the MoP issue has been sorted out. It was not. There is a deadlock over the MoP.

Role of the CJI

The Third Judges case of 1998 clarified the role of the Chief Justice in the functioning of the presidium, and emphasis was laid on the consultative process in the presidium:

- The expression “consultation with the Chief Justice of India” in Articles 217(1) of the Constitution of India requires consultation with a plurality of Judges in the formation of the opinion of the Chief Justice of India. The sole, individual opinion of the Chief Justice of India does not constitute “consultation” within the meaning of the said Articles.

- The Chief Justice of India is not entitled to act solely in his individual capacity, without consultation with other Judges of the Supreme Court, in respect of materials and information conveyed by the Government of India for non-appointment of a judge recommended for appointment.

- Strong “cogent reasons” do not have to be recorded as justification for a departure from the order of seniority, in respect of each senior Judge who has been passed over. What has to be recorded is the positive reason for recommendation.

- The views of the Judges consulted should be in writing and should be conveyed to the Government of India by the Chief Justice of India along with his views to the extent set out in the body of this opinion.

- The Chief Justice of India is obliged to comply with the norms and the requirement of the consultation process, as aforestated, in making his recommendations to the Government of India.

- Recommendations made by the Chief Justice of India without complying with the norms and requirements of the consultation process, as aforestated, are not binding upon the Government of India.

Though government sources deny it, there is no doubt that the deadlock over the MoP hangs like a shadow over the appointment of judges. The government source said that every year about 80 judges retire from the high courts, and the urgency grows for getting in new appointees to fill places vacated by the superannuated.

Says Additional Solicitor General Anand: “There is no consensus between the Supreme Court and the government on the issue of who would take the final call on the question of integrity.”

She said as corruption and merit were the two main concerns of the judiciary and the government, integrity implied that a person was incorruptible and that he or she is also deserving in terms of judicial competence.

TRANSPARENCY LACKING

The mode of appointing judges remains a moot issue. Senior advocate in the Supreme Court, Arvind Datar, told India Legal that the “collegium system” in the Supreme Court has worked well. There have been mistakes but their incidence is not alarming. He is more concerned about the modus operandi with regard to the choice of judges of high courts. He thinks that there is not enough of internal transparency.

He says: “If a high court collegium recommends 15 names to the Supreme Court for appointment as judges in the high court, 11 are accepted and four are rejected. No reasons are given as to why the four are rejected. When the chief justice of a high court has recommended names, he or she would have scrutinised the eligibility of the person before making the recommendation. The Supreme Court should share with the high court chief justice the reasons for rejecting the four persons. And the CJI should even meet the four persons before rejecting their candidacy.”

He says it is not necessary for the CJI to make public the reasons for rejecting candidates, but feels that the SCC’s reasoning for rejecting some should be shared with that high court’s collegium.

Though he was one of the two, along with Anand, of a committee that sifted through thousands of suggestions that poured in for changing the functioning of the collegium at the Supreme Court and make it more open and transparent, Datar is quite clear that there cannot be too much openness, or too much transparency in the process of selecting judges for the Supreme Court. “It is not like a Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) examination and interview, where the marks have to be made public. The choosing of a judge is different, and there is need for being discreet with regard to the processes. Everything with regard to choosing a judge cannot be made public.” What Datar demands is internal transparency. He is worried that the best people could be overlooked because of the peremptory rejection mode of the SCC.

“It is not like a UPSC examination and interview, where the marks have to be made public. The choosing of a judge is different, and there is need for being discreet with regard to the processes.”

—Arvind Datar, advocate

Ministry sources are worried on the same issue of getting the best people to be judges, but they approach the issue from the other end—that of widening the consultation process in order to tap a wider talent pool. One of the main reservations about the existing functioning of the collegium, both at the Supreme Court and high courts is that confining consultation to senior judges who are members of the collegium narrows the range of the talent scan. It is argued that the consultation should not be confined to the four senior-most judges in the Supreme Court and to two senior-most judges in high courts. It is said that in a high court, where there are 60 judges, it is possible that some of the lawyers who could make good judges may not appear before the senior judges who are members of the collegium. Unless suggestions are taken from a greater number of judges, it is quite likely some of the bright lawyers would go unnoticed. It is felt that by not accepting the need for open and wider consultation in looking out for potential judges, the collegium ends up looking at a limited talented pool.

Datar’s point that judges cannot be chosen through a public talent contest is a view that cannot be pushed aside. Choosing judges is not the same as choosing a member of the legislative assembly (MLA) or a member of parliament (MP). At the same time, choosing a judge cannot be fair and efficient if it is restricted to a very limited group of senior judges. Somewhere the balance has to be struck between being too open and being too closed. The Supreme Court and the Modi government would have to reach out to each other to reach the elusive consensus.