By Lokendra Malik

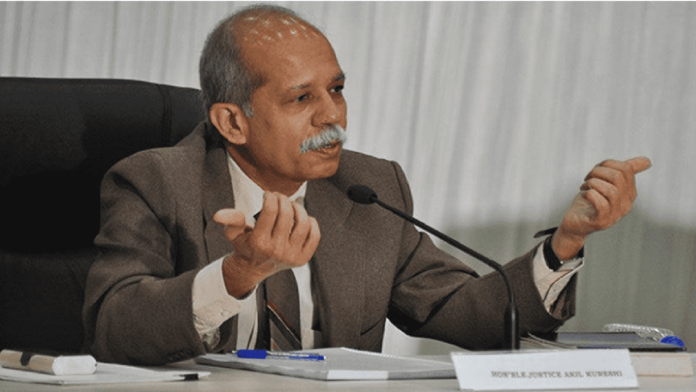

Justice Akil Kureshi, the Chief Justice of Rajasthan High Court, retired on Sunday (March 6) from his office after serving the judiciary for 18 years. He was the senior-most High Court judge in the All-India seniority list of High Court judges. But unfortunately, he was not considered for elevation to the Supreme Court due to reasons best known to the Government and the Supreme Court Collegium.

The legal fraternity knows very well why political elements stopped his appointment to the Supreme Court. He is an honest, brilliant, and thoroughly independent judge who never thought about the repercussions of his judgments and administered justice to the people without fear, favour, affection, or ill-will, as per the letter and spirit of his oath of office.

Speaking on the occasion of his farewell on Saturday, Justice Kureshi spoke of his transfer to Tripura High Court from whence he was transferred to Rajasthan: “Recently, a former Chief Justice of India has written his autobiography. I have not read it, but going by the media reports, he has made certain disclosures. Regarding changing my recommendation for Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court to Tripura High Court, it is stated that the government had some negative perceptions about me based on my judicial opinions. As a judge of the constitutional court whose most primary duty is to fundamental and human rights of citizens, I consider it a certificate of independence.” Further, he said: “What is of greater significance to me is what was the perception of the judiciary which I have not been officially communicated.”

It appears that the Supreme Court Collegium has failed to take a stand against the Government’s perception and withdrew its recommendation appointing Justice Kureshi as Chief Justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court. Though Justice Kureshi did not name the Chief Justice of India, he was referring to former CJI Ranjan Gogoi’s memoirs Justice for the Judge released in December last year, wherein he had said something about this issue.

Also Read: Supreme Court seeks Bihar’s response in plea challenging appointment of DGP Sanjeev Kumar Singhal

Justice Kureshi started his judicial career in 2004 when he was appointed as an additional judge in the Gujarat High Court and became a permanent judge in 2005. He served there for 14 years. During his tenure in the Gujarat High Court, he delivered several significant judgments and earned the reputation of an honest and fearless judge. But he did not get justice from the judge-makers. As senior-most judge of the Gujarat High Court, he had a legitimate expectation of becoming the Acting Chief Justice of Gujarat High Court in 2018, when the Chief Justice retired. Still, his junior colleague was made the Acting Chief Justice.

The bar had protested against this decision, and after that, the Collegium recommended his transfer to the Bombay High Court, where he became the fifth senior-most judge. During his time in Gujarat High Court, he had passed some unfavourable orders against the Government of Gujarat and some powerful ministers of the state government in the Sohrabuddin Sheikh encounter case in 2010. Several constitutional scholars, political pundits, and legal commentators believe that some of his judgments have come in his way to the Supreme Court elevation.

Not only this, but he was also not allowed to join the Madhya Pradesh High Court as Chief Justice and was transferred to a smaller High Court.

Notably, on May 10, 2019, the Supreme Court Collegium headed by then CJI Ranjan Gogoi recommended him for the office of the Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court after considering all relevant factors and being found suitable in all respects. But the Central Government sat on the file and did not clear his name for several months. The Law Ministry sent two communications to the CJI on August 23 and 27 along with some “material” against Justice Kureshi. After that, the Supreme Court Collegium modified its earlier recommendation and recommended his name for the Chief Justice of Tripura High Court on September 5, 2019. The President of India accepted this recommendation and appointed Justice Kureshi to this office. He joined the Tripura High Court in November 2019. But the “material” sent by the Union Government never came out in the public domain.

Also Read: NGT imposes Rs 25 crore fine on bottlers of Coca-Cola, Pepsi for excessive groundwater exploitation

The sanctioned strength of judges in Madhya Pradesh Court is 53, while the Tripura High Court has only 5 judges, including the Chief Justice. Was it a justified modification of the recommendation? I do not think so.

Former CJI Ranjan Gogoi, in his memoirs, justifies the non-disclosure of the material in these words: “It would have done nobody any good if the objection of the government had come into the public domain. The learned judge, at that time, still had several years of service left. I, therefore, requested a senior member of the Collegium to take up the matter with the government. It is to the credit of all concerned that we could avoid a confrontation between the two constitutional bodies (government and judiciary” (Nalini Sharma, India Today, Ranjan Gogoi reveals reasons behind controversial Collegium decisions during his tenure as CJI, December 8, 2021). It is tough to digest this explanation and justification given by Justice Gogoi after his retirement.

Even being the senior-most High Court judge, the Supreme Court Collegium could not consider Justice Kureshi’s name for elevation to the Apex Court even once. Media reports indicate that Justice Rohinton F. Nariman insisted on his elevation to the Apex Court given his all-India seniority. But some other Collegium members, including the then CJI S. A. Bobde, reportedly had a different view about his elevation. Because of this difference of opinion among the Collegium members, a deadlock occurred, and no judge could be appointed to the Supreme Court for around 22 months during former CJI Bobde’s tenure.

After Justice Bobde’s retirement, CJI Ramana-led Collegium recommended the names of nine Supreme Court judges, and the Central Government appointed them quickly. All these appointments were made when Justice Nariman had also retired. During this phase also, Justice Kureshi was bypassed.

Nobody knows why didn’t the Supreme Court Collegium recommend his name even once when the Supreme Court had only one Muslim judge. The constitutional pundits are raising concerns about this practice of the Collegium. Does not the largest minority community not need adequate representation in the Apex Court? There has always been a practice to have at least two or three Muslim judges in the Supreme Court ever since its establishment.

The judge-makers are duty-bound to maintain a balance in the composition of the Bench. There is a lack of transparency in the decision-making process of the Collegium. Nobody knows how the Collegium selects judges and what criterion it adopts to choose judges from different High Courts. Sometimes it takes two or three judges from one High Court and gets none from other High Courts, which remain unrepresented in the Apex Court for a long time.

Under the existing constitutional scheme, practice, and procedure relating to judicial appointments, the Supreme Court Collegium, headed by the Chief Justice of India, has the final say in appointing judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts. The Central Government also plays a significant role in the process, but it cannot override the Collegium. Along with power, comes responsibility. Had the Supreme Court Collegium recommended the name of Justice Kureshi for the Apex Court even once, the Centre had not many options but to clear his appointment after a few months. But the Collegium did not support his case and just recommended his transfer from Tripura High Court to Rajasthan High Court last year.

Justice Kureshi joined the Rajasthan High Court in October last year. The Supreme Court Collegium has to protect honest and independent judges like Justice Kureshi and should not hesitate to recommend their names for the judgeship of the Supreme Court. No government likes independent and fair judges. It is the collective duty of the Supreme Court Collegium to protect such judges. Sadly, the Collegium has failed to safeguard honest and fearless judges who deliver judgments without fear or favour and stand boldly to protect the rule of law, constitutionalism, and independence of the judiciary in all circumstances.

Let me conclude this piece with these thought-provoking words of Justice Kureshi: “So far, there have been 48 Chief Justices of India, but when we talk of courage, sacrifice to uphold the rights of citizens, we remember one who should have but never did become the Chief Justice of India. Justice H.R. Khanna will always be remembered for his shining lone dissenting voice in ADM Jabalpur case.”

The writer is Advocate, Supreme Court of India