~By Vivian Fernandes

The rules which the environment ministry notified for regulation of animal markets on May 23 are absurd, impractical and devious. Its purpose is to stop the slaughter of cattle in the guise of preventing animal cruelty. With this rule, no cattle can be traded for slaughter in the animal markets. The definition of cattle has also been expanded to include buffaloes, which are not revered like cows, and whose slaughter is allowed in all states, barring a few, say, Madhya Pradesh.

The ministry’s heart seems to beat selectively: chicken, sheep, goats, pigs and rabbits have not been included.

Incidentally, this notification from the environment ministry was actually goaded by the Supreme Court. In 2009, Gauri Maulekhi, a trustee of women and child development minister Maneka Gandhi’s People for Animals, filed a writ in the Supreme Court against the illegal movement of buffaloes to Nepal for a big, traditional, five-yearly sacrifice. She said about five lakh animals were slaughtered over two days at the temple in Bariyarpur. (In 2014, she said in her petition, the number had come down to 35,000 because of better awareness and policing). In 2015, the Akhil Bharat Krishi Goseva Sangh, a Wardha-based NGO which wants to end animal slaughter, filed another writ in the Supreme Court against the smuggling of cattle to Bangladesh.

The Court set up a committee with the Director-General of Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB), the armed force guarding the Nepal border, to give suggestions. It had representatives from the Animal Welfare Board, the Animal Husbandry Department, the Border Security Force, the Director-General of Foreign Trade, the Central Board of Excise and Customs, and four states: West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

In his recommendations to the Supreme Court, the DG, SSB, sought restrictions on cattle slaughter, not a ban. Slaughter must be according to the 2006 Food Safety and Standards Act, he said. Rules must be framed to regulate the sale only of healthy animals for “legally authorised purposes”, his affidavit added. (This should include the licensed slaughter of buffaloes and unproductive cattle).

But he also said that the Uttarakhand government order of December 2010 should be the model for the country. That order requires owners to give an undertaking they are selling cattle in pashu melas only for agricultural purposes. Buyers also have to undertake not to sell the purchased cattle before six months (one crop season). But the Uttarakhand government order applies to gau vansh or cattle (that is cows, bulls and bullocks), not to buffaloes, unlike the environment ministry’s rules.

ANIMAL UPKEEP

The recommendations do not offer slaughter as an option for cattle seized from offenders. They have to be rehabilitated. Even farmers are to be “motivated” to give aged cattle to cooperatives, which will issue share certificates equal to the value of the animals and pay an annual dividend from profits earned by selling panchagaavya (plant nutrient made from cattle urine, dung, jaggery, etc), bio-pesticides, farm-yard manure and so on.

The rules prescribe that new animal markets must be covered, their flooring should be non-slippery and bedding must be provided to the animals.

Can this pay for the upkeep of animals which costs about Rupees 54,000 a year till they die? The committee merely says “the economic viability of such a project may be researched by the relevant department”.

Other uses for cattle past their prime, according to the recommendations, is for turning infertile government land fertile by parking aged and infirm animals on them for five years by rotation so that the land is nourished by their dung and urine.

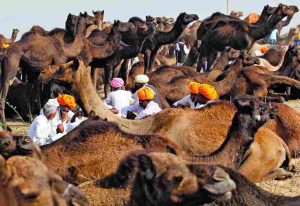

Most animal markets in the country are private and unorganised. They are open fields with troughs and taps. Sandeep Das, whose family operates a cattle bazaar in Mathura every Saturday (for 90 years), says about a thousand buffaloes are traded there every week. (He does not allow cattle). For his services, he charges Rupees 100 per animal. The platform is spread over 20 acres or 81,000 sqm. Of this, only about 2,500 sqm is covered area. No farmer stays overnight, he says. For those who do, there are tin sheds in the neighbourhood.

NEW ANIMAL MARKETS

Now the new rules also prescribe standards for animal markets that would be every farmer’s envy. New animal markets must be covered; it is not clear whether the standards apply to old ones. Their flooring should be non-slippery and bedding must be provided to the animals. There must be a ramp for them to climb down from vehicles. Separate enclosures must be provided for sick animals. There must be an onsite area for disposal of dead animals and facilities for evacuation of dung and urine. The animals must be provided “wholesome food” and “wholesome water”. There should be running water and enough taps and troughs.

Now the new rules also prescribe standards for animal markets that would be every farmer’s envy. New animal markets must be covered; it is not clear whether the standards apply to old ones. Their flooring should be non-slippery and bedding must be provided to the animals. There must be a ramp for them to climb down from vehicles. Separate enclosures must be provided for sick animals. There must be an onsite area for disposal of dead animals and facilities for evacuation of dung and urine. The animals must be provided “wholesome food” and “wholesome water”. There should be running water and enough taps and troughs.

Every owner and buyer will have to give an undertaking that traded cattle will not be given for slaughter. The buyer has to file the documents in quintuplicate, with four different authorities and retain one himself. He must furnish a revenue document attesting that he is an agriculturalist. These have to be retained for six months.

OBJECTIVE

Despite all this bureaucracy, what is the idea behind preventing trading in animals for slaughter at cattle markets? Nuggehalli Jayasimha, an animal activist and lawyer who represented Maulekhi, says it is to prevent unnecessary suffering. In his view, the more the number of transhipment points, the greater the animal’s suffering. He believes cattle markets cannot be made humane so long as suppliers to slaughterhouses control them, as now.

Abattoirs supplying to the domestic market and meat exporters can buy cattle directly through their agents from farmers. The cattle will need a “fitness to move certificate” from registered veterinarians. (Jayasimha says they can be bought for a fee). But the new rules extend the definition of animal markets to “lairages” where animals are kept before slaughter. Does it mean only just-in-time slaughter is permissible?

Jayasimha is only concerned about animal suffering. He is “completely opposed to the ban on beef (cattle) slaughter”. He believes culling is necessary to sustain the dairy and village economy. Eating large animals will also reduce suffering because many small animals will be spared the knife. There are intimations of the demonetisation exercise here. When the government cannot curb a slice of illegality, it proceeds to abolish the whole loaf.

The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, criminalises acts that cause needless pain and suffering to animals. It declares that the killing of animals for food is not an offense if done humanely. But the regulation of cattle slaughter is a state subject because dietary preferences, agricultural conditions and practices vary. By issuing the new rules, the government has exercised power not given by the Act. It has also stepped on the rights of the states.

The committee which made recommendations to the Supreme Court does not seem to have adequately and properly looked into the interests of farmers, meat eaters and those whose livelihood depends on it. The notification says the draft rules were published for one month and public comments were noted. But the meat industry says it was taken by surprise. The Supreme Court’s committee and the environment ministry should have solicited their views. They don’t seem to have done so.

Perhaps they took the cue from Home Minister Rajnath Singh who has vowed to choke smuggling of cattle to Bangladesh. Smuggling is the only way out when licensed exports are not allowed to meet the country’s demand. While addressing BSF jawans on the border in 2014, he congratulated them for driving up the price of beef by 30 percent, according to a news report. He wanted them to be intensely vigilant against smuggling and make beef unaffordable to Bangladeshis.

But in the process, the domestic market has taken a hit.

—The writer is editor of

www.smartindianagriculture.in