~By Inderjit Badhwar

There was once an India in which people on different sides of issues—no matter how deep or broad the chasm—could disagree without being disagreeable or spewing venom. They could compromise or reach a consensus because what mattered were issues like economic, domestic or foreign policies. Today, debate and discussion has been sacrificed at the altar of identity warfare: if you don’t conform to my idea of India, you are guilty of treason or waging war against the state which I have cast in my own image.

The choice of Ram Nath Kovind as BJP’s presidential candidate illustrates this trend. I am sure Kovind is a good, kind, man, well-heeled, educated and honest who would help bolster his party’s standing with the Dalit community. But what about other communities inextricably interwoven into this rich coat of many colours we call India? Kovind has often been quoted as saying that Islam and Christianity are alien to India. He is entitled to his opinion. But does a right to your opinion endow you with the right to your own facts? Kovind’s being the prevailing orthodoxy of the day, any vehement denunciation of this attitude would invite cries of “anti-national” and “go home to Pakistan”.

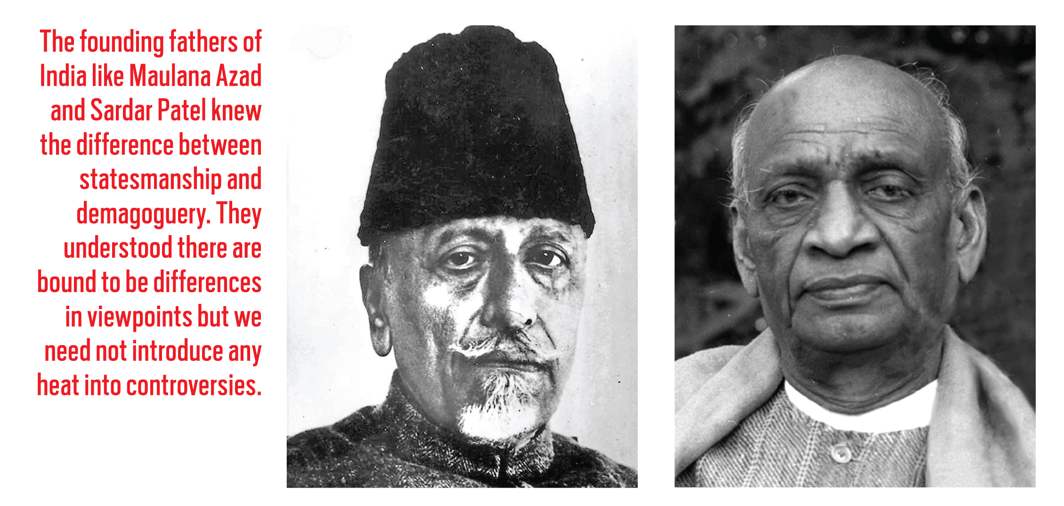

But in the once-upon-a-time India, we listened to one another and even came to terms. Leaders knew the difference between statesmanship and demagoguery. I harken, as I often do, to the debates on sensitive issues by the founding fathers when they were giving us our constitution. Nothing contentious was spared, least of all questions of religion, which brings me to the status of Christians in India who form a little over 2 percent of the population.

The right to practice and convert was one of the touchiest issues which boiled over in April 1947 when Congress leader KM Munshi sought to introduce a provision (Clause 17 in the interim report on Fundamental Rights) prohibiting the religious conversion of a minor under age 18.

In the once-upon-a-time India, we listened to one another and even came to terms. Justice, fair play, reason and compassion ruled public discourse

Indian Christians protested. Member Frank Anthony congratulated Congress members of the Assembly for including the “right to propagate religion” as a fundamental right, but argued: “If you have this particular provision, or if you place an absolute embargo on the conversion of a minor, you will place an embargo absolutely on the right of conversion. You will virtually take away the right to convert. Because, what will happen? Not a single adult who is a parent, however deeply he may feel, however deeply he may be convinced, will ever adopt Christianity, because, by this clause you will be cutting off that parent from his children. By this clause you will say, although the parents may be converted to Christianity, the children shall not be brought up by these parents in the faith of the parents. You will be cutting at the root of family life. I say it is contrary to the ordinary concepts of natural law and justice. You may have your prejudices against conversion; you may have your prejudices against propagation. But once having allowed it, I plead with you not to cut at the root of family life.”

Founding father and pilot of the Assembly BR Ambedkar concurred. He said: “I have no objection to a provision being made that children who have legal and lawful guardians should not be converted without the knowledge and notice of the parents. That, I think, ought to suffice in the case.”

And look at how strongman Sardar Vallabhai Patel responded: “… we who have to live in this country and find a solution to build up a nation, – we need not introduce any heat into this controversy to find a solution. There are bound to be differences in the viewpoints of the different communities, but, as Dr Ambedkar has said, this question has been considered in three Committees and yet we have not been able to find a solution acceptable to all. Let us make one more effort and not carry on this discussion, which will not satisfy everybody. Let this be therefore referred to the Advisory Committee. We shall give one more chance.”

Christian reaction continued to bubble. The National Christian Council Review of June-July 1947 published an open letter by L Sen on the subject of religious liberty.

“All this talk,” said the writer, “about mass conversions being achieved by improper means is absolute balderdash… For several centuries Hindus have kept the so-called untouchables from their temples and still do so in most places. It is a curious mentality that excludes a homeless man from one’s own house and will not allow him to enter someone else’s…. Man has certain inalienable rights which not even a majority vote can take away. One of these rights is that he is free to choose his religion or society, without his motive being impugned by government, whether fascist, communist or democratic.”

The magazine’s August issue, in an angry tirade, advised the Congress members to shun the path of Nazi Germany: “The Congress members of the Constituent Assembly, who wish to make everything Hindu from top to bottom should take a lesson from history. Hitler created a kind of nationalism which brought about the ruin of the German nation. His nationalism created a narrow outlook, and a sense of racial superiority which produced hatred for other nationals, and racial stocks. He gave to the German people those things and ideas which made the Germans feel distinctly different from others, i.e. the Swastika and a special salutation.”

The famous British Methodist missionary, Rev. Stanley Jones, writing in the same issue, noted that there was widespread fear among Christians that in independent India, they would be persecuted, eliminated, or forced to return to the castes from which they had been converted.

He then provides this fascinating account of his own subsequent meeting with senior Congressmen even as the Constituent Assembly debate raged:

“So I went to Sardar Patel, the strong man of the Congress, and asked him what part the missionaries can play, if any, in this new India…. He very thoughtfully replied, ‘Let them go on as they have been going on—let them serve the suffering with their hospitals and dispensaries, educate the poor and give selfless service to the people. They can even carry on their propaganda in a peaceful manner. But let them not use mass conversions for political ends.’ ‘If they do this then there is a place for them in the new India?’ I asked. ‘Certainly,’ he replied, ‘we want them to throw themselves in with India, identify themselves with the people and make India their home.’ This was quite clear and straightforward and from the man who has to do with the question of who shall or shall not come into India, for he is the Home Member.

“I then saw C Rajgopalachari and asked him the same question. His reply was that ‘While I agree that you have the right of conversion, I would suggest that in this crisis when religion is dividing us it would be a better part of your strategy to dim conversions and serve the people in various ways until the situation returns to a more normal state. If you are not willing to do that then I would suggest that instead of ‘Profess, practise and propagate’ as suggested in the Committee, it should be ‘Belief, worship and preach’. Then I further asked, ‘Will the missionaries be tolerated or welcomed as partners in this new India?’ His reply was: ‘If they take some of the attitudes I suggest, then they will not only be welcomed, they will be welcomed with gratitude, for what they have done and will do.’

“The third man I saw was Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, the gracious head of Education in the Central Government. I asked him whether missionaries could be tolerated or welcomed as partners in the making of this new India. His reply was:

‘Do not use the word tolerate. You will be welcomed. There is no point at issue with the missionaries, except at one point: at the place of mass conversions where there is no real change of heart. We believe in the right of outer change where there is inner change, but when masses are brought over without any perceptible spiritual change then it arouses suspicions as to motives…. You will be welcomed gratefully for what you have done not only for India but for other parts of the world such as the Near East.’

Today, debate and discussion has been sacrificed at the altar of identity warfare: if you don’t conform to my idea of India, you are guilty of treason or waging war against the state

“The fourth man to whom I went was the man whom Gandhiji calls ‘the uncrowned king of India’, Jawaharlal Nehru, and when I asked him whether missionaries will be tolerated or welcomed as partners in the making of the new India his reply was: ‘I am not sure as to what is involved in being looked on as partners. But we will welcome anyone who throws himself into India and makes India his home.’

“The fact of the matter is that the greatest hour of Christian opportunity has come in India. I have never had such a hearing in forty years as I have had in these last six months in India. The tensions have been let down. The combativeness against the Christian faith has been eased into an attitude of wistful yearning….

“The Christian Church must now search its own heart and set its own house in order. It must cease from little irrelevancies and give itself to big things. The big thing in India is to present Christ in such a way as to become inescapable in the India to be. And the Church itself must be the message—it must show itself the embodiment of the new order.”

Debate and discussion led ultimately to the Constituent Assembly adopting Article 19 with two minor amendments accepted by Ambedkar. The right of Christians to propagate religion and to convert included minor children. Article 19 later became Article 25 of the Constitution.

Christian scholars, padres, were ecstatic. Felix Alfred Plattner writes in The Catholic Church in India: “Their spontaneous reaction was, ‘Pandit Nehru proves himself a gentleman.’ Pandit Laxmi Kant Maitra, Mr Krishnaswamy Bharati and Mr TT Krishnamachari were congratulated for ‘their noble and courageous defence of the rights of a minority.’”

On August 15, 1948, a year after India became independent, the new nation established diplomatic relations with the Vatican. Justice, fair play, reason and compassion ruled public discourse in the India that was. That was India once upon a time.

—Inderjit Badhwar is Editor-in-Chief, India Legal.

He can be reached [email protected]