Above: Water-scarce Israel has mastered the drip irrigation technique to use every drop of water judiciously. Photo: israel21c.org

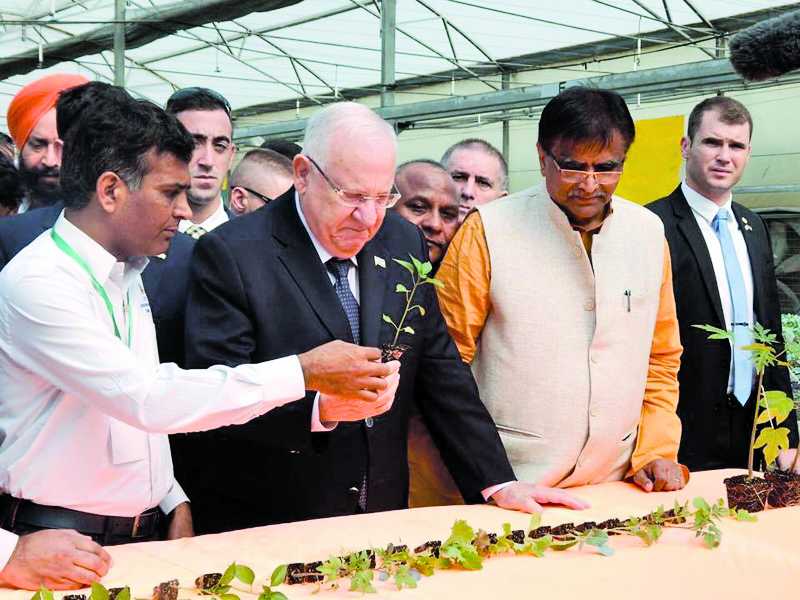

Prime Minister Modi’s trip to this country has underlined the various areas where both countries are cooperating. Already, 26 centres of excellence are helping Indian farmers learn micro-irrigation techniques

~By Vivian Fernandes

Drip irrigation, an Israeli technology, is gaining traction among farmers in India. But it was not the Israelis who propagated it in this country. For that, the credit must go to Bhavarlal Jain, who was not the first to introduce the concept, but is its most ardent champion. In the 1980s, Jain, who expired early last year, decided that drop-by-drop irrigation was just what his largely rain-fed state, Maharashtra required. When an Israeli company turned down his request for the technology, he turned to the Americans. It is another matter that Jain Irrigation, which he founded, later collaborated with an Israeli micro-irrigation company, NaanDan, and wholly acquired it. In fact, in Israel, 90 percent of sown area is under micro-irrigation.

The 2016 Economic Survey made a strong case for more-from-less agriculture, quite like what is done in Israel. So how does it function? Apart from having seeds embedded with technology for efficiency and resilience, the Survey pushed for drip and sprinkler irrigation. Micro-irrigation makes the same quantity of water available to a larger cultivated area. Unlike flood irrigation, it not only reduces wastage of fertiliser through leaching, but also lowers the incidence of pest and disease attacks which happen in conditions of high humidity. The Survey cited a government study of 64 districts in 13 states, which found that micro-irrigation resulted in a 45 percent increase in wheat yield, 20 percent in gram and 40 percent in soybean output. It is “feasible” for rice as well.

This correspondent is on a WhatsApp group of farmers from Maharashtra’s Sangli district who are aiming to harvest 150 tonnes of cane per acre through drip irrigation. Some have come close, producing 135 tonnes from their 18-month crop. Though the district is rich in water, being irrigated by the Krishna and Warana rivers, they found over-watering did more harm than good in terms of pest and disease attacks. Now they give just as much water as cane requires. Fertiliser is also precisely delivered through drips. Tillers are culled to maintain just the optimum population in a field so that the plants get enough sunshine and nutrients.

MICRO-IRRIGATION

But coverage of micro-irrigation in India is quite low, industry representatives lamented during their interaction with the agriculture secretary last year. In Israel, 90 percent of sown area is under micro-irrigation. It is also high in Russia (78 percent), Brazil (52 percent)) and China (10 percent) compared to just 5.5 percent in India. The representatives wanted the subsidy capped at 50 percent of cost in those states where coverage was higher than the national average so that the budgetary allocation would be diverted to those farmers who had not tried it out. Some states subsidised 100 percent of the cost and a few others provided substantial discounts (up to 75 percent). Subsidies seem to have come in the way of adoption as equipment companies were not earnestly marketing the benefits.

India not only needs to use water efficiently, it must extract more from agricultural land which is increasingly being claimed by industrialisation and urbanisation and make small holdings profitable. At the Indo-Israeli centre of excellence in Gharaunda in Haryana, small-holder farmers are coached in growing high-value, off-season vegetables in climate-controlled polyhouses.

In Israel, 90 percent of sown area is under micro-irrigation. It is also high in Russia (78 percent), Brazil (52 percent) and China (10 percent).

The Gharaunda centre supports about 2,200 farmers, says its Deputy Director, Satyender K Yadav, who is also the national cluster head (vegetables) for the India-Israel centres of excellence. It used to supply about 6 million seedlings for Rs 2 each in 2015. Now that subsidy has been withdrawn, it sells 4.5 million a year. Farmers bring their own seed, which the centre incubates and sells for Re 1 each, including the cost of packaging. The seedlings are bred for resilience and uniformity in plastic trays with kulfi-like moulds. This allows the young plants to be transferred to the soil without suffering transplanting shock.

NURTURING PLANTS

During incubation and thereafter, the plants grow in a polyhouses which have double doors to prevent the entry of pests. Water and nutrients are supplied regularly through drips implanted in the soil so that roots do not waste energy chasing them. The quantity of both is regulated with meters that measure electrical conductivity and pressure. Temperature is maintained by exhaust fans that draw in air through wet screens like desert coolers. The temperature should ideally be 28-30 degrees centigrade. Foggers regulate relative humidity and spray nutrients and chemicals. Sun screens keep off harsh light.

Tomato vines drawn with trellis wires grow up to 25 feet and yield fruit for nine months. Secondary shoots have to be clipped for plants to grow tall. Every fourth node has a cluster of tomatoes. Four workers are needed per acre. They have to be diligent and disciplined.

A polyhouse costs Rs 900 a square meter or nearly Rs 37 lakh an acre. Farmers get a subsidy of 65 percent from the Haryana government. Yadav said farmers sell produce worth about Rs 15 lakh a year and save about Rs 5 lakh. Of course, they need to be integrated with markets. They sell in wholesale mandis and also to large retailers like Mother Dairy and Reliance Fresh. Some also export.

ISRAEL FAR AHEAD

Under the Indo-Israel partnership, 26 centres of excellence are to be set up in 16 states. Currently, 16 are operational in nine states. They are focussed on bee-keeping, floriculture, horticulture and so on. A centre for dairy farming is coming up. In 2009, the average Israeli cow gave 10,208 kg of milk a year. In comparison, the Indian one gave 1,172 kg. But dairy management practices are vastly different. Culling of unproductive animals is integral to Israel’s high dairy output. With animal slaughter discouraged in India, Israel’s level of milk productivity will remain an aspiration except in those dairies where efficiency is ruthlessly pursued.

The Indian government does all the funding. Israelis provide technical expertise. They usually train the trainers. The emphasis is on applied research. There is greater reliance on demonstrations.“The farmer usually has a traditional approach. He will not make extreme changes in his farm and he is right. What he is doing, I am sure he has a good reason to do so. And we are not forcing,” said an Israeli trainer.

The farmer can choose what he likes and come back to the centre for more. “We are setting expectations and not bringing a solution in a month. We are doing it at a very conservative pace and we are all the time communicating and talking,” he added.

It is also important to realise that Israel and India are not comparable. One is a nation of 8.5 million people, the other, 1.25 billion. Arable land per person is three times more in India than in Israel (0.04 ha). While one (Israel) has about a quarter million hectares of cultivated land (2,83,000 ha), the other has 140 million ha or 500 times as much. In 2014, Israel exported agri-produce worth about $1.4 billion or 18 percent of the country’s farm production. India’s agri-exports in 2014-15 were $39.20 billion or nearly 13 percent of its total exports.

India not only needs to use water efficiently, it must extract more from agricultural land which is increasingly being claimed by urbanisation.

Israel, its ministry of agriculture estimates, has about 10,000 active farmers. India has 236 million people engaged in agriculture, though it is not the main source of income for most of them. Israel’s agriculture has been hit by high cost of living. Of late, the fall in profitability has been arrested as prices have risen faster than costs. But productivity is declining. The government is importing more food to lower the cost of living. It is also transiting to direct support to farmers instead of indirect subsidies, to ease the pain.

Israel excels in agriculture as a matter of survival. For small holder farmers in India, farming is also a matter of life and death. While not every Indian farmer can do high-tech agriculture, the enterprising ones can attempt it if other conditions permit.

There are some valuable lessons to be learnt from Israel.