Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud on Friday took a pot-shot at those criticising the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts across the country through the Collegium, saying they have prepared a database of top 50 judges, who would be considered for appointment to the Apex Court.

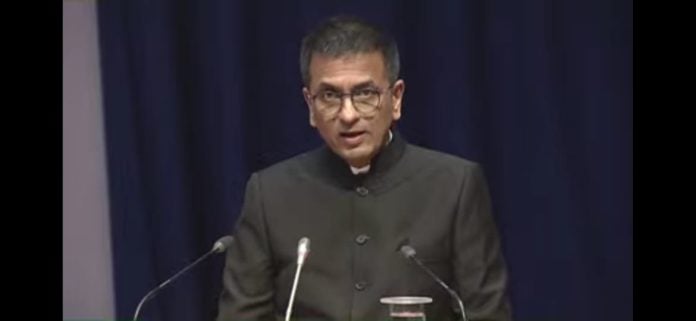

Delivering the Centenary Ram Jethmalani Memorial Lecture in New Delhi, the CJI said that he looked at criticism with an optimistic perspective, as it helped in improving the system for the better.

He said one of the criticisms of the Collegium was that the Supreme Court did not have any factual data to evaluate people considered for appointment.

Stating that it was a work in progress, the CJI said with the help of the Centre of Research and Planning, they have prepared a broad platform, assessing data of top 50 judges in the country, the verdicts delivered by them and the quality of their judgements.

The idea was to make the process of recommending appointments to both the top court of the country as well as High Courts more transparent. He said the same could not be done by sharing discussions in the public realm, but by laying down objective parameters for selection to both the SC and HCs.

He mentioned the Supreme Court onboarding the National Judicial Data grid on Thursday, saying that it would provide real-time tracking of disposal and pendency of cases at the click of a button.

As per the CJI, the Supreme Court registered a disposal rate of 95.34 percent cases in 2023.

He further talked about the e-SCR portal, saying that many young lawyers found it difficult to subscribe to online databases due to the high prices. Dissemination of information was no longer priced as more than 36,016 Apex Court verdicts and 11.6 million High Court judgments were available on the e-SCR portal, he added.

Talking about Ram Jethmalani, he said he was quite overwhelmed to speak about one of the greatest lawyers of the country, whose legacy still resonated in the hearts and minds of people across India.

He asked whether it was possible to clone Ram Jethmalani? Possibly not, because for that, i9t was important to clone the social and political times in which he evolved and flourished, noted the CJI.

He said Ram’s legacy endured due to his relentless pursuit for justice through legal and constitutional means. He lived in times when one could be despondent about the way in which things were turning out, but never gave up his faith in the Constitution.

The CJI recalled the early years of Jethmalani’s legal career. In 1959, he was involved in the prosecution of Nanavati. The last case that was tried by a jury in India. Ram was hired as a watching counsel by the sister of the victim. His role was to help with the prosecution strategy.

It was Ram who wrote the brief for the prosecution lawyer, Y.V. Chandrachud, pointing out eight instances of jury misdirection. The High Court found merit in the prosecution’s arguments and convicted Nanavati.

As per CJI Chandrachud, there began the friendship between Ram and his parents, which endured till the end of their lives.

He recalled Ram’s involvement in the case related to the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Ram gave it his all to prevent the execution. Pardon was rejected. News broke out that the two men convicted were to be hanged at 8 pm the next day. The hanging was stayed by the SC just 14 hours before. Ram had raised a constitutional question over the president’s refusal to grant him a hearing.

He argued that the pardoning power of the President cannot be exercised arbitrarily and that there must be guidelines. ‘Secret guidelines are no guidelines’ he said.

Even though he was not able to get the execution set aside, Ram’s contribution cannot be downplayed. He changed the legal landscape on the death penalty.

He could not protect his clients from execution, but he was able to protect the constitution and the way it has evolved as we know it today. He played a pivotal role in setting up NLSIU Bangalore. He was well connected, but he used his networks for social purposes.

His contribution led to the formulation of a five-year integrated law programme, independent entrance and academic autonomy.

He democratised access to the legal profession by setting up these law schools. Legal education opened up for people without family connections and social capital.

Ram was very vocal about his opposition to the emergency. His heart lay in strengthening the democratic outcomes. He understood that access to justice would be an illusion if lawyers charge exorbitant fees. He was deeply concerned about injustices meted out to common citizens. By some estimates, he charged only 10 percent of his clients and 90 percent of his cases were handled pro bono.