Even as the apex court has warned the centre against arbitrary transfers of judges, the fact is that transfers impinge on judicial federalism and separation of powers and violate basic features doctrine

By Justice Kamaljit Singh Garewal

The Indian Constitution allows the president to transfer a judge from one High Court to another. This very simple and uncomplicated power has been provided in Article 222 of the Constitution. From 1950-1976, there was not a single case of transfer of a High Court judge. Suddenly, during the Emergency, transfer of judges began. The general public perception then was that it was a part government policy to get more commitment from judges to support its socialist policies. If you were suitably socialist, you may stay at home. If you were independent-minded, you packed your bags.

Within a period of two years, 16 High Court judges were transferred from one High Court to another using the power of transfer. Three judges who had been appointed from the judicial service as additional judges were not confirmed. They had to revert to their previous posting as district judges.

Nevertheless, large scale transfer of High Court judges was unprecedented. For 26 years, no transfer had been effected. Then suddenly, someone discovered the president’s power to transfer judges, and 16 were sent packing. The government tried to justify these transfers on the plea of national integrity (whatever that means) and removal of narrow parochial tendencies (a vague, undefined concept). Judges being gentlemen, quietly went to the new places feeling rotten inside. As the phraseology of Article 222 stood, neither was the consent of the judge necessary, nor the opinion of the chief justice binding on the government. It was a pure executive act, a shameless invasion on the independence of the judiciary.

On November 21, The Indian Express published an article headlined, “Don’t Pick & Choose Judges, SC tells Centre”. It must be extremely painful for the government to be told that when dealing with judges’ appointments and transfers, it cannot “pick and choose”, but simply do what the Supreme Court has decided according to the Memorandum of Procedure.

It was reported: “In Punjab, two senior most candidates have not been appointed. This is the problem which arises when selective appointments take place, people lose their seniority. Why will people be ready to become judges?” asked Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul, who is a member of the apex court Collegium.

The same news item also reported on the delay in transferring Gujarat judges. On transfers, Justice Kaul said: “Last time also, I said (it) doesn’t send a good signal. If you pick and choose transfers out of the ones recommended by the Collegium, ultimately they are going to work in one court or the other. It’s not a question of choice of the judges to be appointed. Last time also, I emphasised don’t do selective transfers. It creates its own dynamics, and that is what has happened. One from Allahabad, one from Delhi, and some from Gujarat, six transfers are pending. This is something not acceptable….As per my information, you have issued transfer orders for five judges. For the rest, you have not issued; four of them are from Gujarat,” he added.

And on disturbing the seniority of judges in Gauhati, the paper reported: Senior Advocate Dushyant Dave, appearing for a petitioner, said that in Gauhati HC, the Collegium refused to administer oath to the judge whose name was recommended while another senior’s name was withheld. “Ultimately, the government cleared (it), and the Collegium under the Acting Chief Justice gave oath,” he said. Justice Kaul recorded the court’s “appreciation” of what happened in Gauhati HC and also commended the government “that it took cognizance of it and did something”.

Strange indeed are the ways of the law minister bordering on defiance. A list of five names is sent to his ministry for appointment as judges, but only three are appointed. In another instance, a list of names is sent for transfer, but only some judges are transferred while others are not. The law minister seems to say, it’s my way or the highway. Under the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP), pick and choose for appointment and transfer of judges has already been done. The government cannot pick and choose again from those picked and chosen. This in a country of 1.4 billion people which prides itself as a democracy governed by the Rule of Law.

The Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) regarding appointment and transfer of judges has laid down elaborate steps which must be followed meticulously. Appointment of judges is by the president under Article 217 of the Constitution. The names are sent up by the chief justice after consulting his two senior most colleagues regarding the suitability of the names proposed. The proposal is then sent to the chief minister and the governor with the full set of papers. The governor then forwards the papers to the Union law minister, within six weeks of receiving the proposal. The minister considers the recommendations in the light of such reports as may be available to the government in respect of the names under consideration. The complete set of material is then forwarded to the chief justice of India who consults his two senior most colleagues and forms his opinion with regard to the person to be recommended for appointment to the High Court. After consultations, the chief justice of India sends his recommendation to the law minister, who then puts it to the prime minister, who would then advise the president and the notification issued.

Transfer of judges from one High Court to another is also by the president under Article 222. The proposal is initiated by the chief justice of India whose opinion is determinative. Transfers are made in public interest for promoting better administration of justice throughout the country. The chief justice is expected to take into account the views of the chief justice of the High Court from which the judge is being transferred and the chief justice of the High Court to which the judge is being transferred. The views of one or more Supreme Court judges, who are in a position to offer their views, are also considered. The views of the chief justice of India and four senior most judges should be expressed in writing.

The personal factors relating to the concerned judge, including the chief justice (of a High Court), and his response to the proposal, including his preference of places, should invariably be taken into account by the chief justice of India and the first four puisne judges of the Supreme Court before arriving at a conclusion on the proposal.

The proposal for transfer of the judge, including the chief justice of a High Court should be referred to the Government of India along with the views of all those consulted in this regard. After the recommendation of a transfer is received from the chief justice of India, the law minister sends the recommendation along with relevant papers to the prime minister who will then advise the president as to the transfer of the judge concerned. After the president approves the transfer, the Justice Department issues the necessary notifications in the Gazette of India.

During the emergency, Justice Sankalchand Himatlal Sheth of the Gujarat High Court was transferred to Andhra Pradesh without his consent. He joined the place of transfer, but filed a writ petition in the High Court. The matter came ultimately before the Supreme Court as Union of India vs Sankalchand and another and was decided on September 19, 1977, by a five judge bench consisting of Chief Justice YV Chandrachud, Justice PN Bhagwati, Justice Krishna Iyer, Justice Untwalia and Justice Fazl Ali, by a majority of 3:2 (J. Bhagwati and J.Untwalia were in the minority).

The Supreme Court realised that while the Constitution promoted the democratic value of independence of the judiciary, the executive could use the power of transfer of High Court judges to undermine judicial independence. But as regards the interpretation of Article 222, the Court was divided 3:2. The minority took the view that to preserve judicial integrity and independence, the word “transfer” in Article 222 should be interpreted to mean only “consensual transfer”, i.e., transfer of the judge with his consent and not otherwise because transfer constitutes a stigma on the judge and is very inconvenient to him. On the other hand, the majority took a more literal view of Article 222 and held that this Article did not require the consent of the judge to his transfer from one to another High Court.

As a safeguard against misuse of power by the executive, the majority ruled that “consultation’’ with the chief justice as envisaged by Article 222 had to be “full and effective consultation” and not a mere formality. The opinion given by the chief justice would be entitled to the greatest weight and any departure from it would have to be justified by the government on strong and cogent grounds.

Again, the question of transfer of High Court judges was raised in S.P. Gupta vs. Union of India (AIR 1982 SC 149). Bhagwati, J., reiterated the minority view in Sankalchand that a judge could not be transferred without his consent. In any case, he said that the transfer of a judge could be exercised only in public interest and that transfer by way of punishment could never be in public interest. He emphasised that “whenever transfer of a Judge is effected for a reason bearing upon the conduct or behaviour of the Judge, it would be by way of punishment”.

Transfer being a serious matter, the burden of sustaining the validity of the transfer order must rest on the government. In the instant case, Bhagwati, J., ruled that the transfer of the chief justice of the Patna High Court to Madras High Court was bad because:

(1) there was no full and effective consultation between the central government and the chief justice of India before the decision was taken to transfer him.

(2) transfer was made by way of punishment and not in public interest.

Fazl Ali and Desai, JJ., joined Bhagwati, J., in holding the transfer to be bad. These judges, however, did not agree with Bhagwati, J. in his view that under Article 222, for transfer, the consent of the judge would be necessary. On the other hand, the majority view was that the transfer of the chief justice was valid. The consent of the judge was not necessary for purposes of his transfer. Still the power of transfer vested in the central government was not absolute, but subject to two conditions:

(i) public interest.

(ii) effective consultation with the chief justice of India.

An order of transfer would become a justiciable issue and be liable to be quashed if—(a) it was not in public interest; (b) it was passed without full and effective consultation; (c) if the opinion of the chief justice was brushed aside or ignored without cogent reasons. This is excerpted from page 408 of M.P. Jain’s Indian Constitutional Law Sixth Edition 2010 edited by Justice Ruma Pal & Samaraditya Pal, Senior Advocate.

Of course, now things have drastically changed. Transfers are very common and there is a well laid down procedure which seems to be just and fair to the judiciary and individual judges, but its constitutionality is doubtful.

Article 222 allows the president to transfer a judge from one High Court to another. There was no such power with the King-Emperor under the Government of India Act, 1935, which was federal in nature. Therefore, the power to transfer was a new provision introduced in the Constitution. Whether this is a good practice which improves the administration of justice is an important question. It must be looked at holistically. High Courts are a part of the state judiciary. They are each Courts of Record. They exercise superintendence and control over a vast network of trial courts in the state. It’s easy to see that our judiciary is essentially federal in character. Therefore, transfers of judges impinge on judicial federalism, separation of powers in the state(s), and are violative of the basic features doctrine.

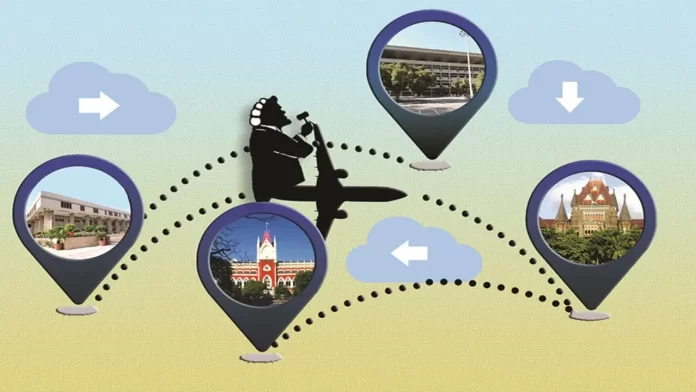

The concept of transfers is unheard of anywhere else. One never hears of a judge from Texas being transferred to California or a judge from England getting transferred to Scotland. In India, you can’t transfer the Speaker of Tamil Nadu (head of the state legislature) to Rajasthan. In the same way, it doesn’t make sense to transfer the chief justice of Allahabad (head of the state judiciary) to Bombay.

Transfers also create many hurdles stemming from lack of knowledge of language, ignorance of local laws and practices, sharing the bench with total strangers and unfamiliarity with the Bar.

May be at some future date, the transfer policy will be undone. But for the coming years, it is here to stay.

—The writer is former judge, Punjab and Haryana High Court, Chandigarh and former judge, United Nations Appeals Tribunal, New York