Above: Relatives carry the body of a child who died in Gorakhpur’s BRD hospital. Photo: UNI

The Gorakhpur tragedy highlights an alarming rise in medical negligence cases in India. The death of 100 babies is a tragic but timely reminder that the government needs to formulate and implement a stronger law against medical malpractice

~By Punit Mishra

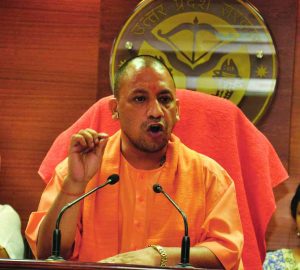

There is considerable irony in the fact that the inhuman tragedy which led to the deaths of nearly 100 babies in a government hospital last week, took place in Gorakhpur, UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath’s constituency. The greater irony is that, as an MP in the Opposition benches, Adityanath, on multiple occasions, had raised questions about the sorry state of healthcare in his constituency, and had singled out BRD Medical College in Gorakhpur, for special mention (see box). It is the hospital where, on August 11, 30 children died due to alleged shortage of supply of liquid oxygen. More children were destined to die, but here’s the real tragedy—the day Adityanath visited the hospital, dead bodies of some babies were whisked out of the back door, so the chief minister would be spared the most tragic symbol of criminal negligence on the part of the hospital authorities.

BRD College itself is a symbol of the state of public healthcare in the country, as exemplified by the bureaucratic blame game and obfuscation over oxygen cylinders and the suppliers. Expectedly, an inquiry committee has been set up to probe the lapses, and equally expectedly, the tragedy and proof of medical negligence will be whisked under the carpet. What Gorakhpur showed was that bureaucratic indifference, corruption, administrative failure, are all factors that lead to medical negligence, with no sign of governments or the courts taking a tough stand and pushing for stronger laws and stricter punishment.

Indeed, an investigation by APN news channel after the Gorakhpur incident revealed that the reason for the rise in medical negligence was largely due to the UP government’s lack of infrastructural support:

- Due to stoppage of 102 and 108 ambulance services in UP’s Bahraich district, pregnant women faced a life-threatening situation. Some were ferried to distant hospitals by rickshaws or on motorcycles, adding to delays and risk to life of the child or mother.

- In a Kanpur government hospital— Murari Lal Chest Hospital—a patient named Pushpa was thrown out as her brother refused to give in to the demands of the hospital authorities. Pushpa was in a critical state and is now is fighting for her life.

- In the Community Health Centre, Bansdih (Ballia), APN reported that the hospital was operating without doctors. Doctors rarely visited the hospital and even if they did, there was no time-table. In the absence of doctors, pharmacists were found operating on patients. The toilets were unusable and medicines were kept in a disorganised manner. The X-ray room did not have electricity, or even a door.

- More shocking, in Miva’s Primary Health Centre in Meerut, a sweeper was found donning a doctor’s coat and dispensing medicines. This was apart from his cleaning duties and the additional job of night guard.

RAMPANT PROBLEM

Uttar Pradesh may be extreme when it comes to indifference towards the public healthcare system, but it is evident in other states as well, leading to thousands of deaths each year. Dr Kunal Saha, who was given the highest-ever compensation in a medical negligence case in India, said: “We not only need separate laws for medical negligence cases, but also new provisions in the law so that people from poor socio-economic backgrounds can fight medico-legal cases on a ‘contingency’ basis as it is in the US.’’

The court proceedings in Saha’s case, involving the death of his wife in a Kolkata hospital, revealed how lightly medical negligence is treated in India. One indicator of that lies in the fact that there is still no central law to tackle medical negligence. The much-vaunted constitution did focus on the need to improve the health of its citizens but instead of treating health as a fundamental right, it was made into a Directive Principle. This basically means that it becomes the responsibility of the states.

Some states have passed what are known as “customary laws” but these are not strong enough to prevent tragedies like Gorakhpur. The result is that India’s healthcare is in a shambles. Moreover, the unholy nexus between private players, suppliers of medical equipment and government doctors and administrators has become so strong that any hope of efficiency and transparency or lack of discrimination between those who can pay and those in financial distress, is a pipe dream.

While the centre, despite numerous Gorakhpur-type tragedies, continues to avoid any responsibility, the medical profession in India has largely been ruled by legislation, which is where the problem lies. The Indian Penal Code, 1860 (sections 52, 83, 88, 90, 80, 81, 91, 92, 304-A, 337 and 338) governs laws on medical negligence in India. The term “negligence” on the part of medical professionals has been variously defined in the courts.

NEGLIGENCE DEFINED

In Jacob Mathew vs State Of Punjab & Anr, the Supreme Court inferred: “Negligence in the context of medical profession necessarily calls for a treatment with a difference. To infer rashness or negligence on the part of a professional, in particular a doctor, additional considerations apply. A case of occupational negligence is different from one of professional negligence.”

The apex court then went on to state: “A simple lack of care, an error of judgment or an accident is not proof of negligence on the part of a medical professional. So long as a doctor follows a practice acceptable to the medical profession of that day, he cannot be held liable for negligence merely because a better alternative course or method of treatment was also available or simply because a more skilled doctor would not have chosen to follow or resort to that practice or procedure which the accused followed.’’

For determining medical negligence, the apex court generally refers to Bolam’s case [1957]. This is an English tort law that lays down the typical rule for assessing the appropriate standard of reasonable care in medical negligence cases involving doctors. It is called the Bolam test and lays down standards which must be in accordance with a responsible body of opinion, even if others differ on it. In other words, the Bolam test states that “if a doctor reaches the standard of a responsible body of medical opinion, he is not negligent”. Bolam’s case holds good in its applicability in India, the Supreme Court noted in the Jacob Mathew vs State Of Punjab & Anr case.

Specifying the criminal and civil prosecution under medical negligence cased, the apex court stated: “The jurisprudential concept of negligence differs in civil and criminal law. What may be negligence in civil law may not necessarily be negligence in criminal law. For an act to amount to criminal negligence, the degree of negligence should be of a very high degree. Negligence which is neither gross nor of a higher degree may provide a ground for action in civil law but cannot form the basis for prosecution.”

REDRESSAL PLATFORMS

Currently, medical negligence cases are tried by consumer courts as well as civil courts. Patients and victims usually approach the consumer forum for compensation while some approach high courts and the Supreme Court. Under civil law, a petitioner can file a case under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986. In normal cases of medical negligence, if the patient can establish that the doctor was negligent and the injury was caused due to that, then he shall be entitled for compensation.

However, in the criminal negligence cases, the negligence should be “gross” in nature, endangering the life of the patient. That brings in a great deal of ambiguity. The definition of gross can vary, as does the question of the doctor’s skill and experience and who exactly was negligent. In Gorakhpur, there are still questions about the oxygen supplier, the payments due to him, who was responsible for signing the cheques and was the shortage of money attributed to the hospital or to the state government. Two doctors/ administrators have been suspended, along with a third doctor who actually did his best to save the children. The fact that he is a Muslim has added a communal element to the tragedy and muddied the waters even further. The evidence shows such critical life-saving equipment like oxygen cylinders was treated so casually and is indicative of the state of public healthcare in India.

In fact, looking at Gorakhpur, the IPC, and judgments in various courts, it is difficult to see whether blame can be fixed and justice served as far as the parents of the dead children are concerned. Section 304A of the IPC covers issues like failure to take precautions. Again, there is a distinction between what is referred to as “the ordinary experience of men’’. Even failure to use special or extraordinary precautions which might have prevented a particular happening, says the IPC, cannot be the standard for judging the alleged negligence.

Similarly, the law says that the standard of care will be judged in the light of knowledge available at the time of the incident, and not at the date of trial. Also, when the charge of negligence arises out of failure to use some particular equipment (as was the case in Gorakhpur), the charge would fail if the equipment “was not generally available at that particular time”.

Such ambiguity in law makes it even harder to determine adequate compensation. The Supreme Court has suggested a multiplier method to determine compensation for medical negligence victims. In the Dr Balram Prasad Vs Dr Kunal Saha & Ors, the Supreme Court noted that “in case of death of victims of negligence, it would be important for the courts to harmoniously construct the aforesaid two principles to determine the amount of compensation under the heads: expenses, special damages, pain and suffering”. In the US, medical negligence cases are heard by state courts where the jury generally gives huge compensation to the patients for any mental agony undergone by them. In India, it is generally based on physical factors, death or damage to organs, limbs, etc.

There is very little chance of the Gorakhpur doctors losing their jobs. So far, the courts have ensured that doctors do not lose their license to practise due to human error.

There is also very little chance of the Gorakhpur doctors losing their jobs. So far, the courts have ensured that doctors do not lose their license to practise because of human error. As the apex court noted in the Kunal Saha vs West Bengal Medical Council and Ors case: “As judges we are humans. We also can commit mistakes. If we are to order what you (Kunal Saha) are demanding, what signal are we sending… for we do not know whether they were actually negligent or not? Only God knows whether they were negligent.”

Pot Calls the Kettle Black

UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath keeps blaming the spread of encephalitis (which claimed the lives of close to 100 children in Gorakhpur) on lack of cleanliness. “The cure of diseases such as encephalitis is hidden in the Swachh Bharat Mission. I been saying this repeatedly as I represent eastern UP.”

UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath keeps blaming the spread of encephalitis (which claimed the lives of close to 100 children in Gorakhpur) on lack of cleanliness. “The cure of diseases such as encephalitis is hidden in the Swachh Bharat Mission. I been saying this repeatedly as I represent eastern UP.”

Here’s the catch. The five-time MP from Gorakhpur has been criticising successive state governments in UP for its failure to contain the scourge of the encephalitis while he was in the Opposition. He specifically mentioned inadequacy of infrastructure at BRD Medical College and Hospital, where the deaths took place last week, while speaking in the Lok Sabha as an MP.

On December 22, 2014, the MP drew the attention of the Union Health Minister to the spread of encephalitis in Uttar Pradesh and asked what steps were taken by the government in this regard. “If something happens at the level of the government of India, what is the machinery of the state government doing? This disease shows the severity of their insensitivity. So far, more than 2,200 patients have been admitted in BRD Medical College till now, in which 607 children have died till yesterday. In the same medical college 607 children die under one roof and no news is made, no action at the state level?” Adityanath had asked. Ironically, as chief minister, the epidemic of encephalitis has spread, and claimed the lives of nearly 100 children in just 48 hours.

NO GUIDELINES

The Supreme Court has, however, taken a strong view of the absence of laws in tackling medical negligence cases. In Dr Balram Prasad Vs Dr Kunal Saha & Ors, the apex court said: “The central and the state governments may consider enacting laws wherever there is absence of one for effective functioning of the private hospitals and nursing homes. Since the conduct of doctors is already regulated by the Medical Council of India, we hope and trust for impartial and strict scrutiny from the body… so as to avoid tragedies where a valuable life could have been saved with a little more awareness and wisdom from the part of the doctors and the Hospital.” In August 2016, the Supreme Court issued notices to the centre, Medical Council of India and all state health secretaries to submit affidavits on standard operating procedures for treatment of patients in ICUs and CCUs (Critical Care Unit).

“India needs separate laws for medical negligence cases”

In 2013, Dr Kunal Saha secured the highest-ever compensation—Rs 5.96 crore—in a medical negligence case which had led to the death of his wife, Anuradha. He now heads an NGO, People for Better Treatment, and submitted a memorandum to the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC), asking for fast-track courts for such cases. PUNIT MISHRA met him for an exclusive interview. Excerpts:

In 2013, Dr Kunal Saha secured the highest-ever compensation—Rs 5.96 crore—in a medical negligence case which had led to the death of his wife, Anuradha. He now heads an NGO, People for Better Treatment, and submitted a memorandum to the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC), asking for fast-track courts for such cases. PUNIT MISHRA met him for an exclusive interview. Excerpts:

You have petitioned for fast track courts. Will a new legislation like the one in West Bengal improve things?

It is nothing but noise in an empty vessel. There is no mention of how long the new Health Commission would take to investigate complaints against doctors/ hospitals or whether the proceedings of their investigation would be made public or not. More importantly, this state Bill has no provision to take any punitive action against guilty doctors as it can only take measures against private hospitals. So our effort to have a fast-track consumer court for medical negligence cases is essential for equitable justice for victims of medical malpractice.

Haryana has set up district-level medical boards to decide complaints of medical negligence against private and government doctors and hospitals.

If these so-called medical boards in Haryana are made up solely of doctors without any independent layman, it would be just like a duplicate “medical council”.

Your experience has shown how difficult it is to fight a case against a reputed doctor or hospital. What measures can a patient from a low income background take to claim compensation in such cases?

This is a million-dollar question. It is not only the “low-income” group, but also ordinary people and the upper income group that find it virtually impossible to fight a legal battle against powerful doctors/ hospitals for justice. The problem does not pertain only to the medical community but to our justice delivery system which has inherent flaws in it. This makes it excruciating for victims of alleged “medical negligence” to carry on a legal fight against powerful medicos. The delays are largely due to lack of adequate number of judges and also unscrupulous advocates who take repeated adjournments for financial gain.

Does India need a separate law to tackle these cases?

India not only needs separate laws for medical negligence cases, it also needs new provisions in the law so that people from poor socio-economic backgrounds can fight medico-legal cases on a “contingency” basis with a written agreement between them and the lawyers, just as it is in the US. There, the lawyer fights the case for free, but if the client wins, he gets 25 percent of the compensation amount. This will help reduce the rampant incidence of “medical negligence” in India and go a long way to save innocent lives.

STATES UP THE ANTE

Various states have also enacted laws and issued guidelines, but mostly to do with private practice. In March 2017, West Bengal enacted the West Bengal Clinical Establishments (Registration, Regulation and Transparency) Act, 2017. The Act, in case of death of patients due to medical negligence, mandates three-year jail terms and trials under the IPC for offenders and fines up to Rs 50 lakh. The Act covers nursing homes, private hospitals, clinics, dispensaries and polyclinics under its ambit, while excluding government hospitals and dispensaries.

Haryana has been more progressive. It has set up district-level medical boards to decide complaints of medical negligence against private or government doctors or hospitals.

The bottomline is that medical negligence does not get the kind of serious attention it deserves from the centre or the states. What is needed is a movement to ensure that the centre and parliament look at the issue afresh, as a Right to Health issue. It needs an amendment in the constitution which establishes that all humans, regardless of economic background, have an equal right to health.

Watch special reports from APN channel related to Gorakhpur tragedy:

—With inputs from Rajesh Kumar