Above: Youngsters hooked to smartphones. Photo: Bhavana Gaur

The dangers posed by this game have revealed the fragile and vulnerable state of children and why parents, schools and society need to protect them from online predators

~By Shailaja Paramathma

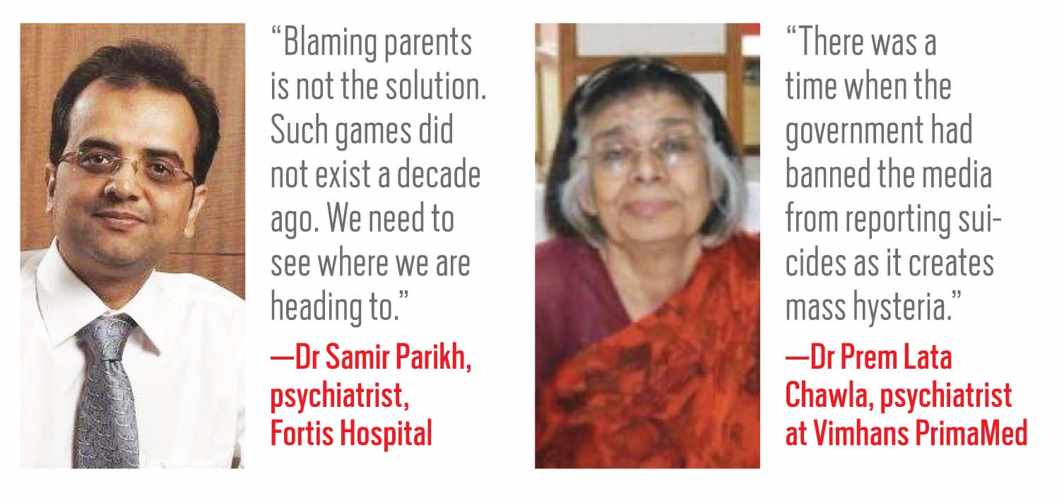

What does the Blue Whale Challenge do to children’s minds and how can they be taught to cope with it? “Adolescents go through social isolation,” explains Dr Samir Parikh, psychiatrist at Fortis Hospital. “During these formative years, they are very vulnerable. When they are challenged with something that is prohibited, they take it up because of it being dangerous.” He says that when they are praised for being daring by their peers, the anticipation of the “high” it gives, takes away their ability to see the consequences of their actions. Even a vulnerable adult who is seeking recognition will behave similarly, he says.

Dr Prem Lata Chawla, a psychiatrist at Vimhans PrimaMed, lays the blame on the media for reporting the suicides allegedly caused by the Blue Whale Challenge. “There was a time when the government had banned the media from reporting suicides as it creates mass hysteria and a spate of suicides follow. Glamourising or sensationalising news creates a suggestion effect to which a susceptible teen can fall,” she says.

India Legal spoke to a group of adolescents who are into online gaming, and it revealed a disturbing trend—most of the 16-year-olds tried to show-off about having tried the Blue Whale Challenge. One teen boasted of having reached Level 24, another claimed he went further but could not be manipulated as he was “not depressed but very strong mentally”. Almost all claimed to know someone who was playing the game presently.

School counsellor Dr Renu Singla says: “These kids are eager to impress. The real danger is for kids who are not doing well in school or those who have few friends.” She says parents come to her complaining of their child not listening to them, and she ends up playing counsellor to the parents as well. “As soon as the parents’ attitude towards the child changes, the kid shows immediate improvement,” she says. Her advice to teachers and parents is to “not behave like they are the boss, but to be firm yet friendly”.

School counsellor Dr Renu Singla says: “These kids are eager to impress. The real danger is for kids who are not doing well in school or those who have few friends.” She says parents come to her complaining of their child not listening to them, and she ends up playing counsellor to the parents as well. “As soon as the parents’ attitude towards the child changes, the kid shows immediate improvement,” she says. Her advice to teachers and parents is to “not behave like they are the boss, but to be firm yet friendly”.

But why are there so many more instances of people in vulnerable or depressive states now than in the previous generation? Chawla says: “There aren’t.” Quoting a line from the novel Americanah by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, she says: “It’s just like what the Americans do. In order to absolve themselves of all responsibility for their actions, they label them as illnesses. Like, thieving becomes kleptomania and being upset is termed depression.”

It is easier for parents to blame their child’s misbehaviour as an effect of peer pressure, whereas acknowledging their own role in the problem takes courage. Laying the onus of a child’s upbringing on the parents, she says: “As a parent, you are not just responsible for your own child but also for his friends. Often, parents of teenagers, who are on drugs blame other kids for the problem. I ask them to alert the other parents too, but they don’t. They would rather go for hospitalisation of the child if it comes to that.”

Children today are electronically more wired than ever before. Even those who don’t own a mobile, use their parents’ phone at home or when they go for tuition. Brother Monachan KK, principal of Montfort school, Delhi, says: “During tuition classes, children are neither with us nor with their parents and they have a phone. I have seen groups of students socialising in markets near tuition centres.” That’s when they could be downloading, playing games or visiting pornography sites.

Children today are electronically more wired than ever before and spend between an hour to three on phones and other electronic gadgets daily.

Parikh says you cannot take away technology. “Blaming parents for a child’s problems is not the solution. Such games did not exist a decade ago, but they do now. Imagine where we will be in another ten years if as a society we do not change?” he asks. Chawla says: “Love your child, set limits and within those boundaries, let him free.”

The suicides in the spate of the Blue Whale Challenge even forced the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) to issue fresh guidelines on safe internet usage in schools. But the guidelines do not mention the game. Titled Guidelines for Safe and Effective use of Internet and Digital Technologies in schools and school buses, they talk about using licenced software on the school PCs, installing appropriate firewalls, profiling what the kids can log on to by keeping the monitors visible to the teacher and sensitising parents about internet safety norms. The CBSE has also advised that “the mobile phone in the school bus to deal with unprecedented emergency should be of basic model without internet facility and data storage”. Welcoming the guidelines, Brother Monachan says: “We are following all these steps regularly but when CBSE sets a parameter, it becomes easier to implement the rules.”

Incidentally, the Blue Whale Challenge can only be played on a smartphone and the use of mobiles on the premises is largely prohibited by most schools. Brother Monachan says that his school does not return confiscated phones. His school also has an incentive programme where a teacher gets 20 points for finding a phone and the kid loses 20 points for using it.

Why are children playing a game which is deemed deadly and which is feared to have caused many deaths around the world? The doctors have one answer: “Curiosity!”

The creator of the game, Philipp Budeikin, who is now behind bars in Russia, reportedly said he had made it to target people going through depression in an effort to “clean the society of biological waste”. Under these circumstances, it is important for parents and teachers to keep communication channels open, listen to the kids and have healthy discussions on what can cause them possible harm.

Calling the game “a symptom of a larger parenting issue,” Chawla says: “In psychiatry, we call a person who wants to commit suicide as being ill. No one wants to die, they are seeking attention.”