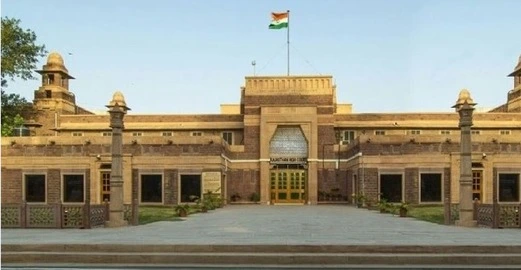

The Rajasthan High Court made the above remark recently while hearing a police official’s petition filed against the rejection of his request for the grant of license for his pistol. “One does not have a fundamental right to keep a weapon and its possession nowadays is more for “showing off” as a “status symbol”, rather than for self-defence, demonstrating that he is an influential person,” the Court observed.

The Court’s observation came while dismissing the petition filed by the police official. The official had sought a pistol license, citing safety concerns due to the size of his inherited 12-bore gun. Despite training and precedent allowing multiple weapon possession, the application was rejected. The state government had turned down his request, stating that one gun license is sufficient, and there is no evidence of a threat to the official’s life. The official appealed against the refusal, but the decision of the state authorities was upheld by the Court.

The bench of Justice Anoop Kumar Dhand noted that the law relating to Arms and Ammunition is governed by the Arms Act, 1959. The Bill was introduced before the Parliament. The objects of the Bill are:

- “(a) To exclude knives, spears, bows and arrows and the like from the definition of “arms”;

- (b) To classify firearms and other prohibited weapons so as to ensure:

(i) that dangerous weapons of military patterns are not available to civilians, particularly anti-social elements;

(ii) That weapons for self-defence are available for all citizens under license unless their antecedents or propensities do not entitle them for the privilege; and

(iii) That the firearms required for training purpose and ordinary civilian use are made easily available on permits;

- (c) To co-ordinate the right of the citizen with the necessity of maintaining law and order and avoiding fifth-column activities in the country;

- (d) To recognize the right of the State to requisition the services of every citizen in national emergencies.

The licensees and permit holders for firearms, shikaris, target shooters and rifle-men in general (in appropriate age groups) will be of great service to the country in emergencies, if the government can properly mobilize and utilize them.”

The legislative objective of the Bill aims to make self-defence weapons accessible to all licensed citizens, except those with questionable antecedents or tendencies that disqualify them from this privilege.

The Arms Act, 1959, defines key terms in Sections 2(c), 2(e), 2(h), and 2(i):

- “Arms” {Section 2(c)} refers to articles designed or adapted as weapons for offense or defence, including firearms, sharp-edged weapons, and machinery for manufacturing arms. However, it excludes items designed solely for domestic or agricultural uses, toys, or non-serviceable weapons.

- “Firearms” {Section 2(e)} encompasses arms designed to discharge projectiles using explosives or energy, including artillery, hand-grenades, riot-pistols, and machinery for manufacturing firearms.

- “Prohibited ammunition” {Section 2(h)} includes ammunition containing noxious substances, rockets, bombs, grenades, shells, missiles, and other articles specified by the Central Government.

- “Prohibited arms” {Section 2(i)} covers firearms that discharge multiple missiles with continuous trigger pressure, weapons designed to discharge noxious substances, artillery, anti-aircraft and anti-tank firearms, and other arms specified by the Central Government.”

The Arms Act, 1959, also regulates the acquisition, possession, manufacture, sale, import, export, and transport of arms and ammunition through Chapter-II. Section 3 mandates that no person shall acquire, possess, or carry firearms or ammunition without a license issued in accordance with the Act and its rules. This licensing requirement extends to specific arms, demonstrating parliamentary intent to control firearm movement.

The aim is to prevent anti-social or anti-national elements from misusing firearms while allowing law-abiding citizens to possess them for self-defence, subject to certain restrictions.

Chapter-III outlines licensing provisions. Section 13 requires applicants to submit applications to the licensing authority. After reviewing the police report, the licensing authority must provide a written order granting or refusing the license, adhering to Chapter III provisions.

Section 14 deals with refusal of licences. It says:

“(14) Refusal of licenses—(i) Notwithstanding anything in Section 13, the licensing authority shall refuse to grant—

(a) a licence under Section 3, Section 4 or Section 5 where such licence is required in respect of any prohibited arms or prohibited ammunition;

(b) a licence in any other case under Chapter II,—

(i) where such license is required by a person whom the licensing authority has reason to believe:

(1) to be prohibited by this Act or by any other law for the time being in force from acquiring, having in his possession or carrying any arms or ammunition, or

(2) to be of unsound mind, or

(3) to be for any reason unfit for a licence under this Act; or

(ii) where the licensing authority deems it necessary for the security of the public peace or for public safety to refuse to grant such a licence.

Section 14 of the Act also says that the licensing authority shall not refuse to grant any licence to any person merely on the ground that such person does not own or possess sufficient property. It further says that where the licensing authority refuses to grant a licence to any person, it shall record in writing the reasons for such refusal and furnish to that person on demand a brief statement of the same unless in any case the licensing authority is of the opinion that it will not be in the public interest to furnish such a statement.

Further, according to Sections 13 and 14 of the Act, licensing authorities have discretion to grant or refuse licenses based on public peace and safety concerns. However, Section 14 overrides Section 13, mandating refusal if certain conditions are met, notably, holding an existing gun license without justified reason for a second one disqualifies an applicant.

The High Court noted that the police official already possessing a 12-bore gun license, failed to provide sufficient grounds for requiring a second license for a revolver/pistol. The size difference between the weapons was an insufficient justification, and thus, the licensing authority correctly refused the additional license, citing the lack of a compelling reason.

The Court also contrasted the right to bear arms in India and the United States or the United Kingdom, noting that the right to bear arms is completely different in India. In the United States, the right to bear arms refers to people’s right to self-defence and it has a constitutional recognition under the Second Amendment of the US Constitution. This amendment empowers the citizens of the USA to retaliate against any tyrannical threat thereby employing self-defence as a primary justification for keeping the weapon/ gun. However, this law is also not absolute in the United States. It is also subject to scrutiny and reasonable restrictions.

However, carrying and possessing firearms is only a matter of statutory privilege in a country, and no citizen has a blanket right to carry a firearm in India, as it is not a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court in Rajendra Singh vs The State of Uttar Pradesh decided on February 13, 2023, that: “It is one of those cases where we find that according to the prosecution case, an unlicensed firearm was used in commission of the offence involving Section 302 IPC also. We have come across cases where there is this phenomenon of use of unlicensed firearms in the commission of serious offences and this is very disturbing. Unlike the Constitution of the United States where the right to bear fire arms is a fundamental freedom, in the wisdom of our founding fathers, no such right has been conferred on anyone under the Constitution of India. The matter relating to regulation of fire arms is governed by Arms Act, 1959, inter alia. It is of the greatest significance to preserve the life of all, that resort must not be made to unlicensed firearms. In particular, if unlicensed fire arms are freely used, this will sound the death knell of rule of law”.

The High Court held that the arms licence is a creation of statute and the licensing authority is vested with the discretion as to granting or not granting of such licence, which would depend upon the facts and situation in each case. The Court further observed that the object of the Arms Act was to ensure that a weapon is available to a citizen for self-defence, but it does not mean that every individual should be given a licence to possess a weapon. “We are not living in a lawless society where individuals have to acquire or hold arms to protect themselves. Licence to hold an arm is to be granted where there is a necessity and not merely at the asking of an individual at his whims and fancies,” the Court said.

The Court found that the police official failed to convince authorities that a second weapon license was necessary, despite already possessing a gun license. The petitioner couldn’t demonstrate a genuine threat to his life warranting two licenses and different firearms, the Court noted.

—By Shivam Sharma and India Legal Bureau