By Kumkum Chadha

It is well known that politicians in India do not have a retirement age. Hence the reluctance to step down and make way for others. Take the Parliament for instance where in the 2024 general elections, India reportedly elected its oldest ever Lok Sabha with the average age of MPs climbing to 56 years. Contrast this to 1998 and post-1999 elections where the average age of MPs dipped to 46.4 years, reportedly the lowest ever and 55.5 years, respectively. Last year’s elections brushed all this aside with the average age going up to 56 years. The good news: it is down from 59 years in the past.

As of now, there are over 350 MPs who are over 50 years of age. One report puts the number to 380 MPs. Of these, 53 are above 71 years and 161 between 61 and 70 years of age. However, the largest representation of MPs is between 51 and 60 years of age: above 30 percent. According to Article 84 of the Constitution, the minimum age of MPs is 25 years for the Lok Sabha and 30 years for Rajya Sabha.

Rewind to May 18, 1949, and the heated debate in the Constituent Assembly. Leading it was Durgabai Deshmukh, a freedom fighter: “It was held for some time that greater age confers greater wisdom on men and women, but in the new conditions we find our boys and girls more precocious and more alive to their sense of responsibilities. Wisdom does not depend on age,” she had then said making a strong plea for reducing the minimum age to enter the Rajya Sabha. Today, if people qualify to enter the Rajya Sabha at 30 years, it is thanks to Durgabai’s amendment which was supported by her colleagues Shibban Lal Saxena and Tajamul Hussain. History records Saxena as one who was arrested for protesting against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and Hussain, a barrister-turned politician.

Rewind yet again to the Plato era, some 2,000 years ago, where age and wisdom were considered synonymous. Or Oscar Wilde, who, some centuries apart, wrote: “With age comes wisdom, but sometimes age comes alone.” Nothing describes the India situation better than this. Politicians stick to power, using it as a glue that has no expiry date. Since there is no retirement age set for politicians under the Constitution, this comes handy in politics, public life and Parliament.

Therefore, when DMK’s TR Baalu was elected from Tamil Nadu’s Sriperumbudur to the Lok Sabha at the age of 82, there were no surprises. Or Samajwadi Party’s Awdesh Prasad from Uttar Pradesh’s Faizabad at 79, now 80 years of age. A year younger is Jiten Ram Manjhi from Gaya in Bihar: the third oldest MP in the current Lok Sabha.

Pitch them against three youngest MPs who are 25: Priya Saroj and Pushpendra Saroj both from Samajwadi Party from Uttar Pradesh and Shambhavi from Lok Janshakti Party elected from Samastipur in Bihar. On this count, the ruling BJP did not make the cut. That notwithstanding, the party leadership did get around the maximum age imbroglio post-2014.

After Narendra Modi took over as prime minister, the BJP imposed a maximum age limit that restricted those above the age of 75 years to either contest elections or hold public office. Though unsaid and unwritten, the rule was then brought in to sideline party veterans. At that point in time, the age bar had targeted LK Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi. The duo was packed off to the Margdarshak Mandal: touted as a body of senior leaders to “guide” the party leadership. That it was defunct from the start is another matter: “a forced retirement” as it was aptly described.

Former Union Minister Yashwant Sinha had then said that BJP had on May 26, 2014 “declared brain dead” its leaders who were above the age of 75 years. Modi, it may be recalled, was sworn in on that day as prime minister for the first time.

Years on, the age bar rule axed others like Anandiben Patel and Najma Heptullah. Patel had resigned as chief minister, two months before she turned 75 years. Heptullah, on the other hand, overstayed by a year. This is not to say that the rule is cast in stone. In fact, the BJP has often bent it to its advantage. “Metroman” Sreedharan, for instance, was fielded as a candidate for elections when he was 88 years old.

Fast forward to 2025: there is a turmoil. The forthcoming month of September is being viewed by some as the ides of March: both symbolically and politically. Modi loyalists like Union Minister Amit Shah would rue it. Maybe; maybe not because an empty space at the top may pave the way for younger leaders to move in. Shah, though he swears by Modi, is younger and ambitious.

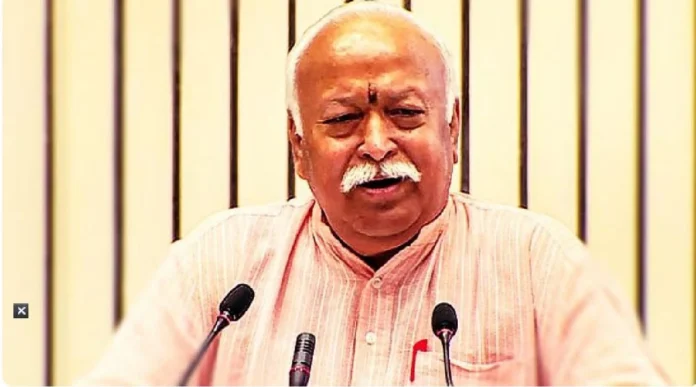

Come September, two powerful people, in the RSS and the government, will be under a lens: RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The two were born six days apart: Bhagwat on September 11, 1950 and Modi on September 17, the same year.

While speculation has been rife for several months whether Modi will self-apply the age rule, there were indications to the contrary. Several BJP leaders jumped into the fray with Amit Shah publicly stating that “Modiji will lead the country till 2029”. The pro-Modi clamour would have continued had the RSS chief not stoked the fire. Speaking at a book launch, Bhagwat said: “Moropant Pingale said that if you are honoured with a shawl after turning 75, it means that you should stop now, you are old, step aside and let others come in,” while releasing Sangh leader Pingale’s biography earlier this month.

Bhagwat did not stop here. “The shawl symbolizes respect, but Pingale understood its deeper meaning—about a generational shift and a polite nudge to step aside for younger leaders”, he said leaving no scope for any misinterpretation.

The message was loud and clear: the 75-age bar, which the BJP has used to settle scores in the past, must be followed in letter and spirit. More than Bhagwat, it is Modi who is in the eye of a storm. Given that the age bar is BJP’s brainchild, it would be applicable to Modi rather than the RSS leaders. Clearly, Modi is in a damned if I do and damned if I don’t situation. If he follows his own rule, it would be curtains down; if he continues, he would be publicly censured. The issue of Bhagwat stepping down may be open ended, but propriety and ethics may force Modi’s hands.

But is that enough to give up the coveted post of a prime minister? Aren’t the trappings of power tempting enough to give a go-by to a principle or rule one had framed a decade ago? Would he rather circumvent time which has perhaps come full circle? On this, the jury is out.

—The writer is an author, journalist and political commentator