By Sanjay Raman Sinha

In what could be a watershed moment for the right of children to quality basic education, a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court has referred a crucial matter to a Constitution bench. The issue: whether the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (RTE), should override the protections given to minority educational institutions under the Constitution.

The bench of Justices Dipankar Datta and Manmohan was hearing pleas from Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra regarding mandatory Teacher Eligibility Tests (TET) in minority schools. They questioned the validity of the earlier Pramati case (2014) and decided to refer the matter to the chief justice of India for consideration by a larger bench.

A two-judge bench cannot overturn a five-judge ruling, but it can request the chief justice to constitute a larger bench for review. The present case demonstrates this mechanism.

At the heart of the conflict is Article 30(1), which protects the right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions, and Article 21A, which guarantees every child the right to free and compulsory education. Exempting minority schools from RTE, the judges noted, effectively denies children these statutory protections.

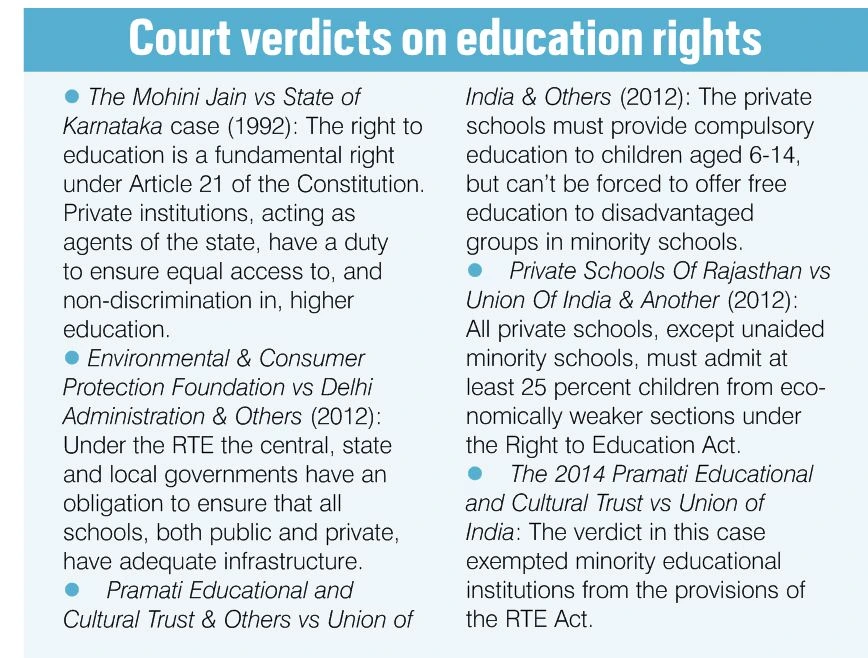

The 2014 Pramati ruling exempted minority schools from RTE obligations. This came after years of litigation:

- In 2002, the 86th Amendment inserted Article 21A, making education for children aged 6-14, a fundamental right.

- In 2010, after the RTE Act came into force, private schools and minority groups challenged its 25 percent EWS quota.

- In 2012, the Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan case upheld the RTE, but exempted unaided minority schools, saying quotas would alter their character.

- In 2014, Pramati extended the exemption to all minority schools, aided or unaided.

The broader question now is how to balance the child’s right to education with minority institutions’ right to autonomy. On one side is the argument that seat reservations amount to “nationalization” and state interference in minority institutions. On the other, child-rights advocates stress that the RTE is “child-centric, not institution-centric”, and must prevail over institutional autonomy.

The outcome of this review will have far-reaching implications—not only for education rights and inclusivity, but also for the interpretation of constitutional protections and the balance between individual and institutional rights.