As the BN Srikrishna Committee begins its work on recommending a new law for data protection, crucial questions on how it would balance right to privacy await resolution

~By Venkatasubramanian

In the midst of the Supreme Court’s hearing on the right to privacy on August 1, the government told the nine-judge bench that it had set up a committee of experts, headed by Justice BN Srikrishna, a former judge of the Supreme Court, to deliberate on a data protection framework.

The government’s decision to set up the committee was an admission that it was concerned about violation of the right to privacy, despite its assertions before the Court that it is not a fundamental right. It was a step aimed at assuaging the concerns of the Supreme Court that in the absence of a robust data protection regime, any compromise with the right to privacy would be fraught with serious consequences for a person’s liberty. That the government did not think such a regime was a prerequisite before it made Aadhaar enrolment mandatory to avail various benefits and services, however, makes its decision suspect.

Notwithstanding this cloud over the government’s intention, the outcome of its deliberations is expected to bring clarity to many issues awaiting judicial determination.

SAFE & SECURE

The Office Memorandum (OM) dated July 31 setting up the Committee says the need to ensure growth of the digital economy while keeping personal data of citizens secure and protected is of utmost importance. The committee has been asked to identify key data protection issues in India and recommend methods of addressing them.

Apart from Justice Srikrishna, chairperson of the Committee, other members include Aruna Sundararajan, secretary, Department of Telecom, Dr Ajay Bhushan Pandey, CEO, UIDAI, Dr Ajay Kumar, additional secretary, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), Prof Rajat Moona, Director, IIT, Raipur, Dr Gulshan Rai, National Cyber Security Coordinator, Prof Rishikesha T Krishnan, director, IIM, Indore, Dr Arghya Sengupta, research director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Rama Vedashree, CEO, DSCI, and joint secretary, MeitY, who will function as the member convener. The Committee may co-opt other members in the group for specific inputs.

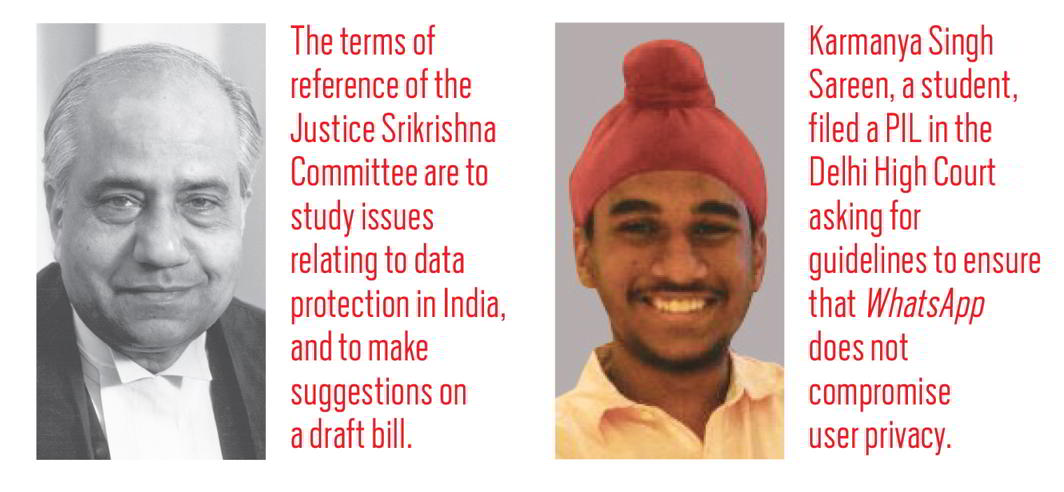

The terms of reference of the Committee are to study various issues relating to data protection, and to make suggestions for consideration of the government on principles to be considered for data protection and suggest a draft data protection bill.

MeitY, in consultation with the chairperson and members, was to collect necessary information and provide it to the Committee within eight weeks of the date of this OM to enable it to start its deliberations. With the Committee expected to start its work early next month, it has led to expectations that a draft data protection law would soon be in place.

To begin with, why is a data protection regime considered important by the stake-holders, including the government? Are they so serious about the right to privacy of the end-users? If so, why can’t they voluntarily ensure that by following a robust code themselves, rather than wait for a legislative regime to ensure compliance with punitive steps for non-compliance?

EYE ON EU BUSINESS?

The stakeholders agree that a law is required, if only to make India appear serious about data protection. As Prashant Reddy, a keen observer, has suggested in Scroll.in recently, the National Association of Software and Services Companies, one of the most powerful industry lobby groups in India, wants a data protection law to enable the information technology and outsourcing industry to get more business from the European Union. A data protection law would help India get “data secure” status from the EU, as India is not currently deemed so under Article 25 of the EU’s Data Protection Directive, which governs the transfer of EU citizens’ data to other countries.

Will a mere legislation be enough to address the EU’s concerns? It depends on what the law is likely to offer. If the law is likely to grant blanket exemption to intelligence agencies, it may fall foul of the EU’s standards.

There is, therefore, considerable suspense on how the Committee would consider the demand of intelligence agencies for exemption from the data protection regime. The Committee has to choose either the US or the EU models for India. The US, Reddy says, does not have omnibus data protection legislation like the EU. The US follows a system of users and service providers entering into standard form contracts in order to encourage innovation.

The US pattern is likely to lead to litigation in India, as seen by the legal challenges being heard by the Supreme Court to WhatsApp’s sharing of its users’ data with Facebook. The Supreme Court has held a number of hearings in this case, which came to it as an appeal against the Delhi High Court’s decision rejecting the plea of the petitioner, Karmanya Singh Sareen, a student.

TECH COMPANIES’ CONCERNS

Apart from this data-sharing dispute, companies like Google, Microsoft, WhatsApp and Facebook are currently embroiled in two major litigations in the Supreme Court. In one case, the petitioner, Sabu Mathew George, has sought action against them for violating the law against pre-natal diagnostic tests. The government has proposed a soft approach to this by requesting that the contents be taken down through a mechanism run by the government as and when complaints are received. The petitioner has expressed dissatisfaction with this proposal.

In the second case, in which the Supreme Court wants these companies to ensure blocking of all videos depicting rape and child pornography, they have sought an in-camera hearing to discuss their proposals. They have serious objections over a draft submitted by a committee set up by the Court, which includes both their representatives and the government.

All these pending cases in the Supreme Court have now to be decided in the light of the recent decision of the Court by a nine-judge bench declaring right to privacy as a fundamental right.

A draft law on data protection is already before the government having been proposed by the Justice AP Shah Committee set up by the erstwhile UPA government. The Committee also submitted a comprehensive report, which has been hailed by civil society.

The AP Shah Committee has recommended that national security, public order, disclosure in public interest, prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of criminal offences, protection of the individual or of the rights and freedoms of others could be grounds of exceptions to right to privacy. But it cautioned that these exceptions must be subjected to certain principles of proportionality, legality and the doctrine of necessity.

Proportionality means that the limitation on the right to privacy should be in proportion to the harm that has been caused or will be caused and the objective of the limitation. Secondly, limitation should be in accordance with the laws in force. Thirdly, limitation should extend only to those grounds which are necessary in a democratic state.

These conclusions are also in consonance with the recent Supreme Court judgment elevating the right to privacy as a fundamental right. At least two members of the Srikrishna Committee, Gulshan Rai and Arghya Sengupta, were also members of the AP Shah Committee. It remains to be seen whether they would follow the broad conclusions and recommendations of the Shah Committee while finalising the specific contours of the new data protection law.