~By Harsh Mander

‘Darkness can never be fought with darkness, only light can dispel the enveloping shadows. And so also a politics of hate can only be fought with a new and radical politics of love and solidarity.’

Many countries in the world are witnessing the rise of authoritarian and chauvinistic political parties, which legitimise hatred against minorities, and suppress liberal and left dissent. In some countries, such parties and leaders are elected to power, such as the United States, Turkey, Hungary and India. In others, like France and Germany, they may not have succeeded in capturing power but their broadening electoral appeal reflects a rising and intensely worrying constituency for hate in growing numbers of countries across the planet.

A major target of these parties (in countries in which Muslims constitute a minority) are Muslim citizens and immigrants. Other minorities are also targeted such as people of colour, other religious, ethnic and sexual minorities. Liberal defenders of these targeted communities, in the media and civil society, are typically attacked, intimidated and gagged by these governments.

A dominant challenge of our times, therefore, is to craft instruments to fight this kind of politics, of what I call ‘command hate’, as this is bigotry and hate that are fostered, encouraged and legitimised by the elected leaders of countries like the United States and India.

Convinced that the politics of hate can be effectively fought only with a politics of love, in an article calling for a resounding people’s response, I wrote, echoing Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Mandela, ‘Darkness can never be fought with darkness, only light can dispel the enveloping shadows. And so also a politics of hate can only be fought with a new and radical politics of love and solidarity. In battling ideologies that harvest hate, we can win only equipped with this love. We need to garner across our land a plenitude of acts of love’.

The test is much greater because the hate that we must fight is not just ‘out there’ but within ourselves or those we are close to, reflected in our resounding silences and our political choices. I wrote, ‘We must resolutely fight…governments and policepersons who betray their constitutional duties; and the hate attackers, ensuring that they be tried and punished under the law of the land. But I believe our greatest, hardest battle will have to be with the bystander. With ourselves. And with our own. We need to interrogate the reasons for our silences, for our failures to speak out, and to intervene, when murderous hate is unleashed on innocent lives. We need our conscience to ache. We need it to be burdened intolerably’.

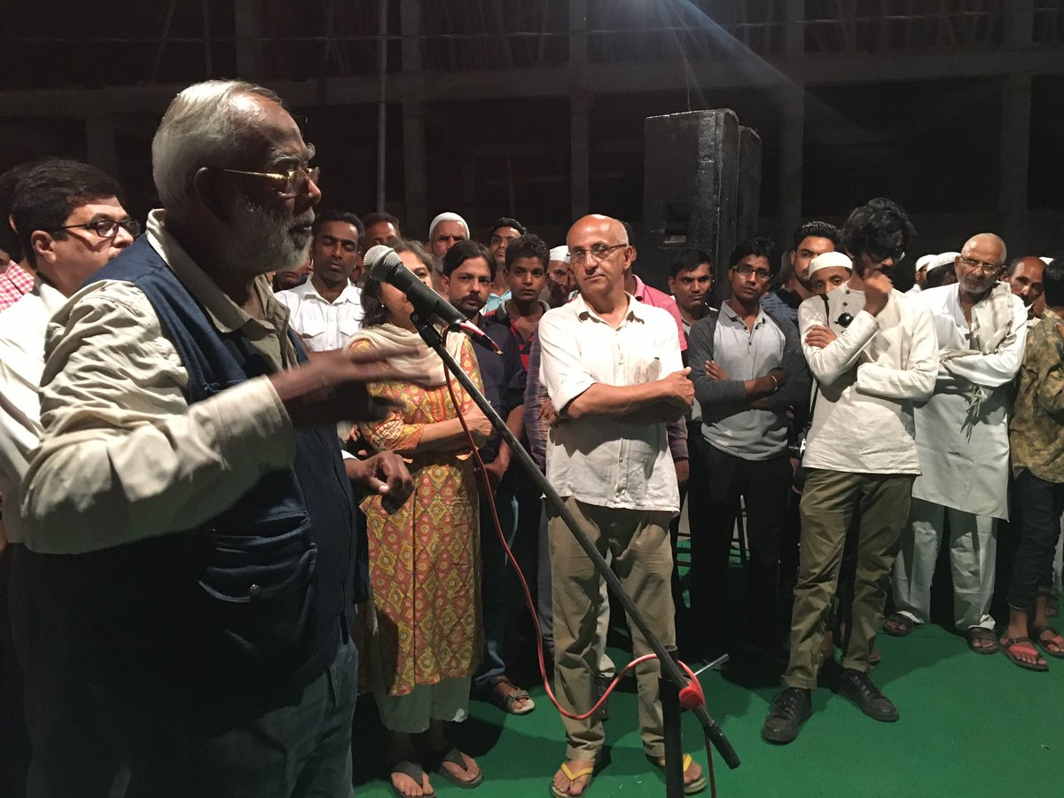

To speak in this way to our collective silences, I proposed a journey of shared suffering, of atonement and of love, called Karwan-e-Mohabbat, or a Caravan of Love. I proposed that we travel across the country, to meet families who lost their loved ones to hate lynching violence. With pain and shame, to seek from them our collective forgiveness, an atonement, to try a little to share their suffering. And to speak to them of our solidarity and love, and our resolve that justice must be done.

Within just a month after my appeal was published, the Karwan (Caravan) set off on 4 September 2017. Entirely crowd-funded, and with an exceptional group of volunteers – writers, journalists, social workers, teachers, lawyers – we intersected India from east to west over a month, traversing Assam, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Delhi, Western Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat.

As we travelled, I wrote an update late every night as we tried to catch a few hours of sleep.

The Karwan found everywhere minorities, most of all Muslims, living with fear, hate and state violence as normalised elements of everyday living. Distraught families could not understand the sources of so much hate. We also found Dalits brutally attacked by upper caste neighbours if they displayed any assertion. We found single women, branded as witches, subjected to inconceivable medieval cruelty by family and neighbours. Christians in tribal regions are in fear because of violence against priests, nuns and places of worship. But the foremost targets of hate violence by lynching and police killings are Muslims, and it is they who have most abandoned hope.

I have written elsewhere: ‘Against Muslims, the hate weapon of choice is public lynching. We read of lynching of Blacks in America as public spectacles, watched by white families in picnics. In today’s India, this same objective of lynching as public performance is accomplished with the video camera. Most lynch attacks are filmed by the attackers, with images of their victims humiliated, cringing, begging for their lives…We found that lynch videos are widely and avidly shared among young Hindu activists. Probably as evidence of what they see as their valorous exploits. As proof that the state will protect them. As public exhibitions of the humiliation of their enemy communities. And for drafting new recruits to militant Hindu supremacist formations’.

The police in almost all the fifty families we met during our travels in eight states registered criminal charges against the victims, and did all they could to protect the accused with kid from being charged, and from spending time in jail. Even more worrying, we found that the police has increasingly taken on the work of the lynch mob. There are tens of instances in both states in which the police itself kills Muslim men, charging them to be cattle smugglers or dangerous criminals, and claiming that they fired at the police.

And we found in all these local communities profound and pervasive failures of compassion. We encountered very little acknowledgment, regret or remorse amongst the upper-caste Hindu communities in any of the states we travelled. They remain convinced that somehow their Muslim and Dalit neighbours deserved their cruel deaths to lynch mobs or police bullets.

They expressed their anger and hostility to the Karwan at many points. In one leg, they became violent. The Karwan had resolved the next morning to place flowers at the site of Pehlu Khan’s lynching, in his memory and the memory of others like him who fell to hate violence. the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, the Hindu Jagran Manch and the Bajrang Dal announced that they would not allow the Karwan to enter Behror and pay tribute at the lynch site. The local administration also tried hard to dissuade us. They said that a furious mob had gathered there with stones and sticks and would cause me harm. I said I was prepared for it, and would not agree to discard the plans of a floral tribute. I said I would go there alone as I did not want to risk any of my Karwan colleagues being attacked or hit by a stone.

I quote from my update: ‘I began to walk to the site, but the police physically blocked me. I then sat on the ground in a spontaneous dharna (sit-in). They would have to either arrest me, or allow me to walk to the location and make my floral tribute. I sat for about half an hour, as they confabulated.

Finally they relented.

With two fistfuls of marigold flowers, and surrounded by a few policepersons, I walked the couple of hundred years to the spot where the ageing cattle trader Pehlu Khan had been cruelly lynched by a mob. It was a dirty nondescript stretch of a sidewalk. I knelt down there, and said, ‘I am not a believer, so I cannot pray. But I believe in insaniyat aur insaaf- humanism and justice. Therefore, for humanism and justice, I place these flowers here. In memory not just of Pehlu Khan, but of hundreds of others like him who have fallen to hate violence across our land’.

I returned to the bus, and the police bundled us rapidly into the bus. As we drove past, the protesting men threw a few stones at the bus.

On the way, people of the small town Kothputli had planned a small welcome to the Karwan. But in the presence of the police, a bunch of young men arrived, tore down the banners and threw away the flowers. The police said they were helpless to stop them. The police then asked just two organisers to meet the bus outside the police station. I emerged with a couple of colleagues, and the policemen said we had only a couple of minutes. They handed over packets of packed breakfast, and a few men gathered. One of them took off his shoe to throw, as the bus drove away. We stopped the bus long enough to throw out flowers.

The Karwan now had police escort vehicles both ahead and following its bus. It was only with this that the state administration would allow the Karwan to travel through Rajasthan. A sad day when a caravan of love can travel only with the protection of the police. We don’t need or deserve protection; it is the bereaved families who we have met these days of the Karwan who the police should protect, but it is they who they fail so profoundly’.

It was clear that the government was troubled by the Karwan, as its discourse of love, and the evidence it gathered about how widespread was the fear and hate that its policies had fostered. We learnt that all big newspapers and TV channels were advised to blank out news of the Caravan. Many, but not all, complied with these pressures. Despite everything, many stories – my daily updates, and several articles by Karwan travellers – appeared both on-line and in print.

In a television debate when the Karwan was being blocked from placing flowers, a leader of the RSS angrily decried my credentials (following up with many tweets describing me as a scoundrel, and the social media soon filled with abusive trolls slandering my work). He also said that the funds of ‘my’ NGO must be investigated thoroughly.

Not wasting time, just four days later, the Centre for Equity Studies, of which I am a founding member and Director received tax notices. I issued this press note: ‘In a television debate on 14 September 2017, in NDTV’s Left, Right and Centre anchored by Nidhi Razdan, I joined by phone from the Karwan bus. Mr Rakesh Sinha of the RSS during the debate made angry personalised attacks against me. He also said that I was against the RSS. I replied that I am indeed against the ideology of the RSS, because its belief in a Hindu Rashtra (Nation) contravenes the Indian Constitution. During this same debate, Mr Sinha said, in a barely veiled threat, that the funding of ‘my’ organisations would be investigated. The next morning, despite stone-throwing mobs, I did finally prevail in placing flowers at the site of Pehlu Khan’s lynching.

Four days later, an organisation of which I am the Director and one of the founders, the Centre for Equity Studies, received by email a notice under Section 143 (2) of the Income Tax Act for a Full Scrutiny of the income tax returns of the Centre for Equity Studies for the year 2016-17.

The Income Tax Department may claim that this is just a routine notice. But the timing of the notice shortly after the public threat for getting the funding of ‘my’ organisations investigated, and the fact that less than 1 per cent of returns are scrutinised, suggest that this could well be an act of state vengeance and intimidation.

I would also like to point out that the Centre for Equity Studies had nothing whatsoever to do with the Karwan-e-Mohabbat. It brings out the annual India Exclusion Report, and works with homeless persons and other vulnerable groups.

We are happy to subject ourselves to any scrutiny, as we believe in public accountability. But I would like to state categorically that no amount of state intimidation of the organisations that I am associated with, would succeed to silencing my public dissent with policies and ideologies that I believe are detrimental to India’s constitutional values’.

The work that the Centre does is precious to me. But at times like this, I believe that there is no higher duty than public dissent. This is not an act of particular valour, just that no other option is acceptable. As I wrote to my colleagues, ‘They can cancel our FCRA (permission to receive foreign funds). Shut down the organisation. How does it matter? This would be an infinitely small fraction of the suffering we bore witness to in the Karwan.’

—The writer is a former IAS officer and activist