Above: The Talwars walk out of Dasna Jail on October 16, three days after they were scheduled to be released from imprisonment. Picture: Anil Shakya

~By Inderjit Badhwar

The Indian penal system does not display the same speed in releasing prisoners after they have served their terms or been found not guilty by the courts after their detention as it does in locking them up. The recent, most glaring, example of this was the three-day delay in releasing from behind bars Nupur and Rajesh Talwar who were ordered to be set free by the Allahabad High Court which found them innocent of the crime of having slain their daughter Aarushi. To someone who has not experienced the loss of freedom and mobility during periods of incarceration, three days or so may not sound like a big deal. But for people like the Talwars who spent over four years of their original life sentence in Dasna Jail, every day of freedom, starting from the moment the judge freed them, is a new lease of life.

The delay was caused by glitches in the labyrinthine mesh of rules and regulations that govern the administration of India’s network of prisons which often vary from state to state, jail to jail. This set of laws, often contained in antiquated manuals, unrevised since the days of the British Raj, continue to bedevil the prison-based system of deterrence with which the legal system tries to punish and prevent crime. The biggest evil of this system is that while it is designed to punish proven wrongdoers, it also winds up oppressing thousands upon thousands of innocent Indians who have nowhere to turn to for relief.

The Rule of Law is based on a cardinal precept of natural justice under which you are held innocent unless proven guilty in court. What is horrifying in India is that as of now, close to three lakh people still awaiting trial are languishing in jail. The majority of them is poor, illiterate, and belongs to the Adivasi, minority, and Dalit communities, according to statistics published by Delhi’s National Law University (NLU). A significant number of them has not even met a lawyer or been allowed to appear at a bail hearing or even had court charges framed against them. They have been confined only on the strength of FIRs and police reports and charges. Shockingly, these detenues or “undertrials”, as they are called, account for two out of three prisoners in India’s penitentiary system—about 67 percent—a number way higher than other democracies in the world. According to a 2017 Amnesty International report, India has the third highest undertrial population in Asia. Arguably, it is India’s most ignored problem. In other words, there are twice as many undertrials in India’s prisons as there are convicts.

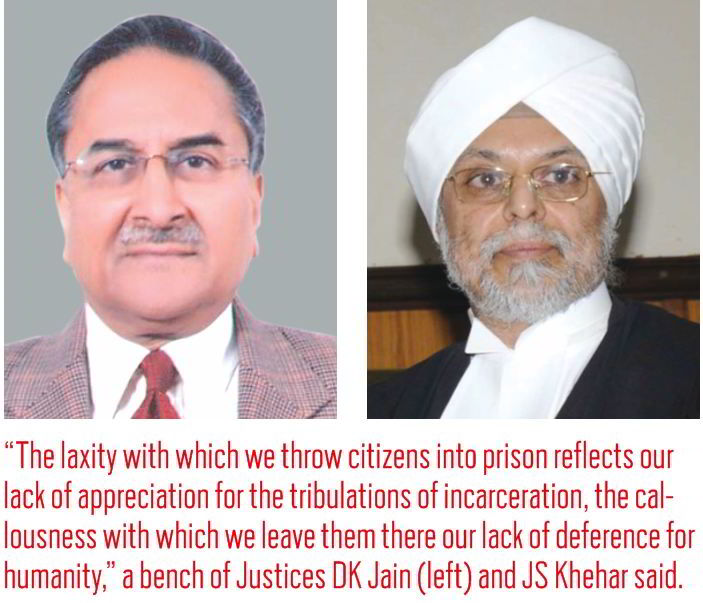

And these undertrials—really a misnomer because a large proportion of them has yet to even appear in a trial court—are subjected to harsh, inhuman or sub-human conditions and bureaucratic tyranny prescribed in jail manuals. It is not as if the Government of India is not aware of this ugly reality. Ever since Independence, “successive governments have acknowledged the problem of excessive undertrial detention, but have not done enough to address it”, reports Amnesty International. But as the Supreme Court observed in Thana Singh vs the Bureau of Narcotics in 2013: “The laxity with which we throw citizens into prison reflects our lack of appreciation for the tribulations of incarceration; the callousness with which we leave them there reflects our lack of deference for humanity.” This observation came from a bench comprising Justices DK Jain and JS Khehar.

The Justices added: “It also reflects our imprudence when our prisons are bursting at their seams. For the prisoner himself, imprisonment for the purposes of trial is as ignoble as imprisonment on conviction for an offence, since the damning finger and opprobrious eyes of society draw no difference between the two.” In a sharp rebuke aimed squarely at the attitude of the state, they added: “The plight of the under trials seems to gain focus only on a solicitous inquiry by this court, and soon after, quickly fades into the backdrop.” The Court made these remarks following a grant of bail to Thana Singh who had been rotting in prison for more than 12 years, awaiting trial under the narcotics law.

According to a 2017 Amnesty International report, India has the third highest undertrial population in Asia. Arguably, it is India’s most ignored problem. In other words, there are twice as many undertrials in India’s prisons as there are convicts.

A recent study named “Prison Reforms in India”, prepared for legislators by the Lok Sabha Secretariat, notes that shortly after the Constitution was framed, India’s leaders were aware of the need for humanitarian steps in this field. It notes that in 1951, the Government of India invited the United Nations expert on correctional work, Dr WC Reckless, to undertake a study on prison administration and to suggest policy reforms. His report titled, “Jail Administration in India”, made a plea for transforming jails into reformation centres. He also recommended the revision of outdated jail manuals.

Highlights of the Lok Sabha report:

- In 1952, the Eighth Conference of the Inspectors General of Prisons also supported the recommendations of Dr Reckless regarding prison reform. Accordingly, the Government of India appointed the All India Jail Manual Committee in 1957 to prepare a model prison manual. The committee submitted its report in 1960. The Model Prison Manual 1960 is the guiding principle for prison management in India. Accordingly, the Home Ministry, in 1972, appointed a working group on prisons. It brought out in its report the need for a national policy on prisons. It also made an important recommendation with regard to the classification and treatment of offenders and laid down certain principles.

- The Mulla Committee (1980), chaired by Justice AN Mulla, recommended making available proper food, clothing, sanitation; proper training and cadre organisation for prison staff; establishing an all-India service called the Indian Prisons & Correctional Service; after-care, rehabilitation and probation to be an integral part of prison service; the press and public to be allowed inside prisons and allied correctional institutions periodically, so that the public may have first-hand information about the conditions of prisons and be willing to co-operate in rehabilitation work; undertrials in jails to be reduced to a bare minimum and kept away from convicts.

- Following a Supreme Court direction (1996) in Ramamurthy vs State of Karnataka to bring about uniformity of prison laws, a committee was set up in the Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPR&D). In 1999, a draft Model Prison Management Bill (Prison Administration and Treatment of Prisoners Bill, 1998) was circulated to replace the Prisons Act of 1894. Meanwhile, a Model Prison Manual was prepared in 2003 and circulated to all state governments.

- In response to several directions by the Supreme Court, a Home Ministry-appointed expert committee designed another Model Prison Manual in 2016 and circulated it to all state governments. Its key features include an emphasis on prison computerisation, special provisions for women prisoners, focus on after-care services, prison inspections, rights of prisoners sentenced to death, repatriation of foreign prisoners and enhanced focus on prison correctional staff.

- Despite Home Ministry advisories emanating from the Fifth National Conference of Heads of Prisons of States and Union Territories (2016), there has been little or no headway in unclogging and modernising the prison system. As the Lok Sabha Secretariat report bluntly concludes: “Though various bodies have studied the problems of prisons in India and laws are made for improving jail conditions, it is a fact that many problems plague our prisons. In many cases, prisoners come out of jails as hardened criminals more than as reformed wrongdoers willing to join the mainstream social processes. The emphasis on correctional aspect needs to be strengthened through counseling programmes by experts. The mindset of the prison staff must change. The management of prisons must be marked by discipline and due regard to the human rights of prisoners. Prison reform is not just about prison buildings, but what goes on inside them that needs to be changed. The focus must be on the human rights of prisoners besides improving their amenities.”

A few months back, Amnesty International hosted a seminar called “Bail Not Jail”, which included eminent panellists like filmmaker Vetrimaaran; renowned expert on police reforms Dr Murali Karnam and former Karnataka Inspector General of Prisons Kuchanna Srinivasan. One key recommendation was implementation of Section 436A of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC).

According to Section 436A, CrPC, where an undertrial prisoner other than one accused of an offence for which death has been prescribed has been under detention for a period extending to one-half of the maximum period of imprisonment, he should be released on his personal bond, with or without sureties

This was a key reform measure undertaken by parliament in 2005. It reads: “There have been widespread reports that undertrial prisoners were detained in jail for periods beyond the maximum period of imprisonment provided for the alleged offence. As remedial measures Section 436A has been inserted to provide that where an undertrial prisoner other than the one accused of an offence for which death has been prescribed as one of the punishments has been under detention for a period extending to one-half of the maximum period of imprisonment provided for the alleged offence, he should be released on his personal bond, with or without sureties. It has also been provided that in no case will an undertrial prisoner be detained beyond the maximum period of imprisonment for which he can be convicted for the alleged offence.”

Unfortunately, as the Lok Sabha report rightly observed, notwithstanding high-level committees and Supreme Court admonitions, there has been little or no movement on prison reform and the right of detenues to free and speedy legal services. This is an egregious and continuing violation of human rights and a breach of international treaties to which India is a party. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) remains the core global accord on the safeguarding of the rights of prisoners. India ratified the Covenant in 1979 and has to incorporate them into domestic laws. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESR) states that prisoners have a right to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health.

Unfortunately, as the Lok Sabha report rightly observed, notwithstanding high-level committees and Supreme Court admonitions, there has been little or no movement on prison reform and the right of detenues to free and speedy legal services. This is an egregious and continuing violation of human rights and a breach of international treaties to which India is a party. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) remains the core global accord on the safeguarding of the rights of prisoners. India ratified the Covenant in 1979 and has to incorporate them into domestic laws. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESR) states that prisoners have a right to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health.

“Apart from civil and political rights,” says the Lok Sabha Secretariat report, “the so called second generation economic, social and human rights as set down in the ICESR also apply to the prisoners. The UN Standard Minimum Rule also made it mandatory to provide a separate residence for young and juvenile delinquents away from adult prisoners. Subsequent UN directives have been the Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners (United Nations 1990) and the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (United Nations 1988).”

One reason the reforms are not implemented is that prisoners, alas, are not a vote bank. Also, in the state subjects under List-II of the Seventh Schedule in the Constitution, the management and administration of prisons falls exclusively in the domain of state governments, and is governed by the Prisons Act, 1894, and Prison Manuals of the respective state governments—all creatures of the oppressive British colonial system.

In 2013, RC Lahoti, a former Chief Justice of India, made an impassioned written plea to Chief Justice Altamas Kabir, about “inhuman condition of prisoners in 1,382 prisons across the country”. The apex court suo motu treated this as a public interest writ petition and passed an interim order which stated: “Unfortunately, even though Article 21 of the Constitution requires a life of dignity for all persons, little appears to have changed on the ground as far as prisoners are concerned and we are once again required to deal with issues relating to prisons in the country and their reform.”

Nothing, it seems, will change unless we truly heed Gandhiji’s advice that “crime is the outcome of a diseased mind and jail must have an environment of hospital for treatment and care”. And the Supreme Court, in its wisdom, must find it fit to hold in contempt all authorities who have treated with contempt its repeated admonitions and prescriptions to correct one of this country’s most shameless displays of disregard for basic human rights.

—Inderjit Badhwar is Editor-in-Chief, India Legal.

He can be reached [email protected]