Above: Women protesting against the dilution of Section 498A in Delhi; (inset) Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra. Photo: K.M Vasudevan/lawyerscollective.org

Decades of activism were undone when the apex court in July diluted this statute. But in a reassuring move, the Court has now promised to revisit it

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

It is an order that has brought hope. On October 13, the Supreme Court observed that it disagreed with its earlier order diluting Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, a statute often invoked in dowry-related domestic abuse cases.

Responding to the writ petition filed by NGO Nyayadhar, the Court’s three-judge bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra, and Justices AM Khanwilkar and DY Chandrachud announced that the July 27 order rendered in the Rajesh Sharma vs State of UP case by the division bench of Justices AK Goel and UU Lalit “really curtails the rights of the women who are harassed” and prima facie, the guidelines issued by it lay “in the legislative sphere”.

Advocate-on-record Manju Jaitley confirmed that though the Maharashtra-based NGO had raised a limited issue, the apex court departed from tradition and decided to revisit the judgment. The NGO’s prayer was for the inclusion of women in family welfare committees sought to be formed by district legal service authorities so as to achieve at least a 2:1 sex ratio. The Court also issued notices to the ministries of home affairs, and women and child development and the National Commission for Women to revert with their views. Senior advocates Indu Malhotra and V Shekhar have been appointed amici curiae to assist it.

Pertinently, a group of 16 women’s rights organisations, including Lawyers Collective, Jagori and the All India Women’s Democratic Association, had earlier sent a memorandum to then CJI JS Khehar to review the July 27 judgment. Former additional solicitor general and senior advocate Indira Jaising had said: “The sooner it is overturned, the better it is for the rule of law.”

DEAD LETTER

The Supreme Court’s July 27 order has been widely criticised for having undone decades of achievements of women’s rights movements. After a spate of bride-burning incidents and harassment by in-laws for dowry, Section 498A was instituted in 1983 to protect the victims. It states: “Whoever, being the husband or the relative of the husband of a woman, subjects such woman to cruelty shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine.” The term “cruelty” is explained as any conduct that amounts to dowry harassment or that may drive the wife to commit suicide.

However, the top court in July thought it fit to issue a set of directions to “prevent the misuse of Section 498A of the IPC”. It asked for the constitution of family welfare committees to look into cases before any FIR is filed. The committees, which will comprise para-legal volunteers, social workers, retirees and housewives, must submit a report to the police station within a month of receipt of the police complaint, based on which action would be initiated. Thus there would be no immediate arrest of the culprits. Yet their bail application, post-arrest, would be decided “as far as possible on the same day”. Recovery of disputed dowry items from the accused would not be ground for denial of bail. In the case of NRIs, their passports would not be impounded and a red corner notice would not be issued. Family members of the accused are exempted from personal appearance during trial which would be conducted as far as possible via video-conferencing.

However, the top court in July thought it fit to issue a set of directions to “prevent the misuse of Section 498A of the IPC”. It asked for the constitution of family welfare committees to look into cases before any FIR is filed. The committees, which will comprise para-legal volunteers, social workers, retirees and housewives, must submit a report to the police station within a month of receipt of the police complaint, based on which action would be initiated. Thus there would be no immediate arrest of the culprits. Yet their bail application, post-arrest, would be decided “as far as possible on the same day”. Recovery of disputed dowry items from the accused would not be ground for denial of bail. In the case of NRIs, their passports would not be impounded and a red corner notice would not be issued. Family members of the accused are exempted from personal appearance during trial which would be conducted as far as possible via video-conferencing.

As critics have pointed out, these directions are faulty on three counts. Untrained in law and without well-defined qualifications, family welfare committees would bring in their own biases while evaluating a case and very likely function as non-State vigilante groups just like landlords, resident welfare associations and gau rakshaks. The culprit would be given a long rope and every chance to flee. And the victim, with no one by her side and already under tremendous pressure to withdraw her police complaint, would probably end up being coerced to do the same, ironically giving power to the false notion that most such complaints are frivolous ones over “trivial” issues.

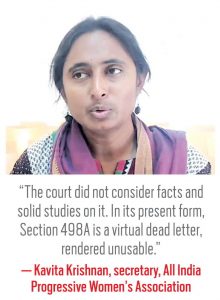

Contrary to the common misperception among law enforcement agencies that this statute is being widely misused by “mendacious”, privileged and vindictive women to get back at their aged and infirm in-laws, Section 498A is an underused law, said Kavita Krishnan, secretary, All India Progressive Women’s Association. “The court did not consider facts and solid studies on it and was driven by misconceptions and stereotypes. In its present form, Section 498A is a virtual dead letter, rendered unusable,” she told India Legal.

MYTH OF MISUSE

Truly enough, National Commission for Women data shows only 0.03 percent of women filed a case under Section 498A annually. It also shows the numbers of false cases filed for other crimes such as cheating, criminal breach of trust and abductions are significantly higher, proving that all laws are open to misuse. And low conviction rates, which often happens due to shoddy police investigation, exist across the board for all crimes. Hence, the argument that this meant women were filing false cases is wrong.

The Nyayadhar petition, too, states: “Sec 498A is most helpful instrument in the hands of victim women [sic] to get immediate relief from law and police station, but guidelines issued that [sic] no immediate arrest to accused person and his family. As the result, the fear of law is totally vanished… we may say that ‘the soul of Section 498A is now dead and now Sec 498A is valueless’.”

Ritwik Bisaria of the Men Welfare Trust raises the point that in October 2010, Section 41A was modified to rule out direct arrest for any offence with less than seven years’ jail term, so the no-automatic arrest directive is not a new development. He mentions the 2014 Arnesh Kumar vs State of Bihar and the 1994 Joginder Kumar vs State of UP judgments to rest his case. But the shocking fact remains that according to the National Crime Records Bureau, statistics from which were heavily cited in the July order, 21 dowry deaths still take place in India daily.

Also, the argument of gender neutrality of laws put forward by opponents of an effective Section 498A is defeated by the very existence of the custom of dowry. Hopefully, the few strong laws that years of struggle have earned us will bring justice to the victims.