While Padmaavat is set for release after a baptism of fire, filmmaker Amol Palekar’s petition in the Supreme Court, to be heard this month, contests the validity itself of the Censor Board

~By Usha Rani Das

It is a remarkable coincidence that Padmavati will finally be released—the Supreme Court additionally lifted the ban enforced by some states—around the same time that filmmaker Amol Palekar’s petition comes up in the apex court. He had filed it in 2017 against the Cinematograph Act (1952) and Cinematograph Rules (1983) which guide the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). The petition challenges the very validity of the Board as a “censorship board”. In his petition, he states: “…the CBFC (Central Board of Film Certification) routinely demands cuts of scenes or dialogue, failing which it denies certification to films for arbitrary reasons: Remove ‘mann ki baat’ from a dialogue; get an NOC from the PM’s office for the title of the film ‘Modi ka Gaon’, saying films are unsuitable for release because they are ‘lady oriented’…”

The travails of Padmavati and its makers only support his argument. The politically-motivated protests and bans by BJP state governments aside, the CBFC cleared it with five modifications:

- Change the disclaimer to one that clearly doesn’t claim historical accuracy.

- Change the title from Padmavati to Padmaavat—as the filmmakers have cited their creative source to be the fictional poem, Padmavat, not history.

- Modifications to the song, Ghoomar, to render the depiction befitting to the character being portrayed.

- Modifications to the incorrect/misleading reference to historical places.

- Addition of a disclaimer which clearly makes the point that the film in no manner subscribes to the practice of sati or seeks to glorify it.

In another case, the film Mohalla Assi was cleared with an “A” certificate after a two-year battle in Delhi High Court on January 10. The film, based on Kashinath Singh’s Hindi novel Kashi Ka Assi (2004), explores the globalisation of Varanasi city and the influx of foreigners. The Board, then headed by Pahlaj Nihalani, had refused to clear the film, stating it was “highly derogatory of humans, cult, culture, religion including but not limited to mythology”.

Though the CBFC’s main function is to certify films, over the past months it has made headlines for alleged moral policing. Hence, reputed actor and director Palekar was forced to make an attempt to address the problem through his petition in the Supreme Court. The petition challenges Section 2 (definition of the CBFC), Section 3(1) (constitution and purpose of CBFC), Section 4(3) (which requires the applicant director/producer to edit the movie or alter it so that the certificate may be issued), Section 5(1) and 5(2) (provides for the establishment of advisory panel to advise the CBFC on the impact of a certain movie on the general public) Section 5A (power to issue certificates and categories of certificates) Section 5B (principles guiding the issuance or non-issuance of certificates). As Palekar told India Legal: “The CBFC has always been very active in protecting the moral fibre of the country. Inciting hostility between groups, or a likelihood of grievously offending the sentiments of a particular group/community/religion, or the possibility of a dangerous law and order situation, have been used as tools to curb artistic expression.”

The petition is scheduled to be listed in court this month. Gautam Narayan, the lawyer representing Palekar, told India Legal: “We are challenging the way the Board has interpreted its powers as defined in the Cinematograph Rules, 1983. The Board is there only to certify, not to censor. We think members of the film fraternity or people who are well-educated about films should be chosen as members. This will ensure the artistic freedom of the country.”

SC and freedom of expression

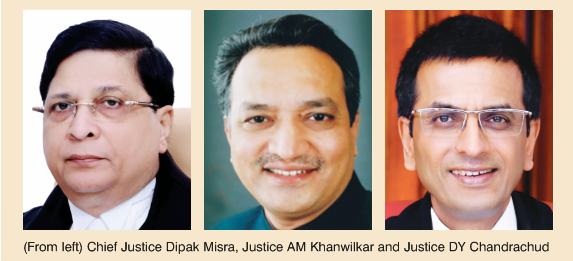

Laying emphasis on freedom of expression, the Supreme Court bench of Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra and Justices AM Khanwilkar and DY Chandrachud on January 18 ordered that no state can selectively ban the release of the controversial film, Padmaavat. The producers of the movie, Viacom18 Media Private Limited, had filed a petition before the apex court a day after the movie was banned in Haryana.

The CJI, while passing this interim direction, said that once the Central Board of Film Certification had given its certification, no state could prohibit the release of that particular film and it was the “duty and obligation of states to maintain law and order”. CJI Misra said “We are concerned that a film is being banned from being exhibited… expression of a creative content… my constitutional conscience is shocked…”

Senior advocate Harish Salve, who appeared for Viacom18, said the Gujarat government had banned the movie in order to maintain peace and harmony, but added that law and order is not a ground for banning a movie. He said Lady Chatterley’s Lover was not published in the UK for over 30 years and Penguin Books faced obscenity charges over it, but it was selling. The CJI remarked that in the 1970s, those who had not read the book were considered ill-qualified to discuss certain topics.

The bench said: “If Bandit Queen could pass the test of the Supreme Court… And we are not here to disrespect our history. This film is based on a poem.” The bench said there are films such as Dhobi Ghat and Deshdrohi. Justice Misra added: “If you go by this, 60 percent of literature, even classical literature of India, cannot be read.”

Justice Chandrachud said that “valuable constitutional rights are at stake”. Emphasising the “right to freedom of speech and expression”, the bench said: “It has to be borne in mind, expression of an idea by anyone through the medium of cinema which is a public medium has its own status under the Constitution and the Statute. There is a Censor Board under the Act which allows grant of certificate for screening of the movies. As we scan the language of the Act and the guidelines framed thereunder it prohibits use and presentation of visuals or words contemptuous of racial, religious or other groups. Be that as it may. As advised at present once the Certificate has been issued, there is prima facie a presumption that the concerned authority has taken into account all the guidelines including public order…”

CENSORSHIP VS CERTIFICATION

The CBFC was constituted under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, which aims to provide for the certification of cinematograph films for exhibition. The law, however, also allows the CBFC to require modifications to be made to a film before providing the certification. Under Sections 4 and 5A, the CBFC may (after examining the film, or having it examined):

- Sanction the film for unrestricted public exhibition, subject to requiring a caution to be provided stating that guardians may consider whether a film is suitable for viewing by a child if required (i.e. grant a U or UA certificate).

- Sanction the film for public exhibition restricted to adult viewers (i.e. grant an A certificate).

- Sanction the film for public exhibition restricted to members of a profession or class of persons based on the nature of the film (i.e. grant an S certificate).

- Direct that certain modifications are made to the film before sanctioning the film for exhibition as described above, or

- Refuse to sanction the film for public exhibition.

Additionally, the Act proffers principles on the basis of which the CBFC may refuse to certify a film—“if a film or any part of it is against the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite the commission of an offence”. These principles are further supplemented by the certification guidelines issued by the central government in 1991. These guidelines provide five objectives for film certification under the Act:

- The medium of film remains responsible and sensitive to the values and standards of society.

- Artistic expression and creative freedom are not unduly curbed.

- Certification is responsive to social changes.

- The medium of film provides clean and healthy entertainment.

- The film is of aesthetic value and cinematically of a good standard.

In order to meet these objectives, the CBFC should ensure that films do not contain scenes that glorify/justify activities such as violence, drinking, smoking or drug addiction, scenes that denigrate women, scenes that involve sexual violence or depict sexual perversions, or scenes that show violence against children. These guidelines, however, are vague. Over time, the CBFC has increasingly used this power to direct cuts in films, leading it to be commonly referred to as the “censor board”.

These provisions were challenged for the first time in 1970 by filmmaker KA Abbas but the Supreme Court had reinstated the need of pre-censorship. In the KA Abbas vs Union of India case, a five-judge bench had ruled that cinematographic films in theatres were the most influential media of mass communication affecting the social mind and, hence, the exercise of censorship under the Cinematograph Act was valid and necessary.

After this decision, the CBFC started using its power of certification as a means of pre-censorship by routinely demanding cuts of scenes or dialogue. In its 2014-15 audit, the Comptroller and Auditor General found that the “CBFC had converted 172 ‘A’ films into ‘UA’, and 166 ‘UA’ films into ‘U’ during 2012-15, without taking any law or provision into account. It had also observed that there were inconsistencies in the time taken by CBFC for issue of certificates to various producers.”

The tenure of Nihalani was mired in controversy. In 2015, when he took over as chairperson, he circulated a controversial list banning the use of “objectionable” and “abusive” words. It was later withdrawn after a majority of the members voted against it. It was Nihalani who had asked the makers of An Insignificant Man (a documentary on Arvind Kejriwal) to seek a “No Objection Certificate” from Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Films like Lipstick Under My Burkha, Udta Punjab, Aligarh, Haraamkhor, Spectre, Raman Raghav 2.0 also faced Nihalani’s blue pencil. After the Udta Punjab controversy, the ministry of information and broadcasting set up a committee in 2016 to evolve broad, but clear guidelines/procedures to guide the CBFC. The committee, headed by noted filmmaker Shyam Benegal, had stated in its report that it was not for the CBFC to act as a “moral compass”, and decide on what constitutes glorification or promotion of certain issues.

The committee’s report suggests that the only function of the CBFC should be to determine which category of viewers a film can be exhibited to. The committee’s report has suggested new guidelines, with the following objectives: (i) children and adults are protected from potentially harmful or otherwise unsuitable content; (ii) audiences (and parents/those responsible for children) are empowered to make informed viewing decisions; (iii) artistic expression and creative freedom are not unduly curbed in the classification of films; (iv) the process of certification is responsive to social changes. The committee’s recommendations are yet to be implemented.

Palekar has asked in his petition that the committee’s report be considered. He even challenged the Abbas case decision by stating it is not valid as times have changed and also the medium of showcasing one’s artistic work. He argues that colonial laws cannot be applied to media like YouTube and other common social media platforms where audiences are in millions and content in thousands.

Ira Bhaskar, professor of cinema studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University and a former member of the CBFC stated in a column in The Hindu (April 2017): “The name of the Central Board of Film Censors was changed to the Central Board of Film Certification in 1983 and that pretty much explains the responsibility of the CBFC, which is to certify films according to age. The certification should make it clear that UA means watching films under parental guidance. It is the responsibility of the parent to ensure that he or she accompanies the child. Movies certified Adult should not be censored at all. The ratings are meant to indicate the category under which the films are certified as U, UA, S, and A. And as long as you certify films, you need a certification board. Like the West, we should have a child-centric certification, one which seeks to protect our children against adult content. The certification board should certify and not censor.”

“Process is the punishment”

Actor-director Amol Palekar’s petition in the Supreme Court raises some crucial questions about the functioning of the CBFC. He had also challenged certain provisions of the 47-year-old Cinematograph Act. He spoke to Usha Rani Das. Excerpts:

The CBFC has become a censorship body rather than a certification body. How did this happen?

Even before the post-2016 saffronisation of Indian politics, the CBFC has always been very active in protecting the moral fibre of the country as well as the nation’s sovereignty and integrity. Inciting hostility between groups, or a likelihood of grievously offending the sentiments of a particular group/community/religion, or the possibility of a dangerous law and order situation, have been used as tools to curb artistic expression.

Somewhere a perverse belief is set as a bottom line that artistic endeavour ought to be confined to amuse/entertain and shall not point out the warts and blemishes of our society. Such prejudiced and irrational beliefs lead to repressive actions which further spread undemocratic sentiments amongst the masses. The CBFC under Pahlaj Nihalani was used as a political weapon to curb dissent while homogenising the culture as per the political agenda. Thus the institutionalised censorship became so blatantly ridiculous that CBFC lost any credibility.

The CBFC does in fact have a deterrent value so much so that at the level of scripting, the filmmakers consider the potential dangers of not getting a “U” certificate or avoiding certain expression/scene; such an atmosphere sans freedom certainly affects artistic creativity as well as their creation. The certification process is an example of the old adage, “process itself is the punishment”.

You have challenged the appointments of the CBFC in your petition, stating that there are no specific guidelines for the appointments. What guidelines should there be?

In fact, I am seeking a declaration that the CBFC in its present form is incompetent to carry on functions under the Cinematograph Act because, among other reasons, the Board members are appointed without any qualifying norms set through the said Act.

In addition to the unqualified members, the guidelines which are supposed to be the guiding principles while ascertaining any film, are completely vague, arbitrary, overbroad and imprecise. This in itself amounts to unreasonable restriction on artistic freedom.

The Benegal Committee Report had suggested giving representation to regional cinema, issues relating to women/children, persons of eminence comprising writers, artists, lawyers, entrepreneurs, mass media, etc and who have an in-depth understanding of Indian society, such as sociologists and anthropologists and psychologists.

You have faced flak from the Board numerous times. Have you ever felt that some political parties/bodies or political agenda were influencing the Board’s decisions?

You have faced flak from the Board numerous times. Have you ever felt that some political parties/bodies or political agenda were influencing the Board’s decisions?

No, I do not think that there was ever any influence or pressure from a particular political party. Regressive traits and puritanical values are ubiquitous; misogyny, moral policing, jingoism, etc prevail across all the political parties. Two reasons are always given to curb artistic freedom, namely, it may hurt the sentiments of a certain section of society and it may create a law and order situation. In the garb of protecting society, the ulterior motive is to control society.

My first encounter with censorship was in 1971 when the Maharashtra Stage Scrutiny Board wished to ban my play in Marathi called Avadhya. After a prolonged fight, I was granted an “A” certificate to perform without any cuts. Later in 1973 my other play in Marathi called Vasanakand was banned by the Maharashtra government. Same good old grounds of “morality” and “possible law and order situation” were flashed for both the plays. However, no such apprehended situation was caused after the performances.

In 1975, the CBFC had objected to the “thematic content” of my film in Hindi, Daayara. The Board offered an ‘A’ certificate plus demanded a few cuts. My films Thaang and Quest were bilingual versions of a story depicting a man-woman relationship against the background of homosexuality.

In 2007, the CBFC cleared the English version with an “A” certificate, however, it recommended banning the Marathi version. Facing this ridiculous situation was an eye-opener as to the regressive mindset of the CBFC as an institution. One of the members actually told me that the sensibilities of English-speaking audiences are different from those of Marathi-speaking audiences; hence the Marathi audiences needed to be protected more. When I requested them to give me the ban order in writing, they backed off, fearing legal action from me.

Most of the people who are protesting the release of the film do not even know the actual story. Are these protests based on reason or fact?

Most of the time, in our country, people react without having any deeper information, let alone knowledge, about the alleged controversial issue. Dealing with anything rationally is always difficult compared to resorting to vandalism and violence. Artistes have long been at the receiving end, often violently so, of the intolerant mob.

Balbir Krishan, whose art echoes his homosexuality, faced a violent attack in Delhi; MF Husain had to be in exile in his twilight years after facing death threats; Taslima Nasreen is still unable to find sanctuary in India; Salman Rushdie’s permission to speak at a literary festival in Jaipur was withdrawn right at the penultimate moment; Mumbai University withdrew Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey from its curriculum; a statue of Dadoji Konddeo was spirited away overnight from its prominent location in Pune’s Lal Mahal; and Joseph Lelyveld’s book Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India was banned in quick succession by the Gujarat and the central governments.

We have a long and ignominious history of abject prostration before intemperate, anti-intellectual mobs. One feels at a loss after seeing from the recent Padmavati controversy that nothing much has changed over the last five decades.

POLITICAL APPOINTMENTS

In the petition, Palekar also challenges the political appointments of the Board. He seeks “to quash certain provisions which provide for appointments of the members of the board and/or the examining committee, or the revising committee, or even the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FACT), without specifying any qualifications—leading to subjective, erratic, arbitrary interpretation of over-broad, imprecise guidelines by unqualified members, which in itself is very unfair and amounts to an unreasonable restriction on the filmmakers’ freedom of speech”.

Under the Act, the Board consists of non-official members and a chairman, all of whom are appointed by the central government. Due to this, more often than not, the Board’s decision is politically influenced. When Nihalani became the chairperson, he had told NDTV “he was proud to be a BJP person”. Palekar says: “CBFC under Pahlaj Nihalani was used as a political weapon to curb dissent while homogenising the culture as per the political agenda.”

In 2015, Leela Samson, the then chairperson, and 12 other board members had resigned following a row over the speedy clearance given by the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) for the release of the film Messenger of God, featuring former Dera Sacha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh. The film had first been rejected by the reviewing committee of the Board as it promoted superstition and blind belief. Samson had cited “interference, coercion and corruption of panel members and officers of the organisation who are appointed by the ministry” as reasons for her resignation.

In 2015, Leela Samson, the then chairperson, and 12 other board members had resigned following a row over the speedy clearance given by the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) for the release of the film Messenger of God, featuring former Dera Sacha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh. The film had first been rejected by the reviewing committee of the Board as it promoted superstition and blind belief. Samson had cited “interference, coercion and corruption of panel members and officers of the organisation who are appointed by the ministry” as reasons for her resignation.

Earlier, in 2014, its CEO, Rajesh Kumar, was arrested for allegedly demanding Rs 70,000 for clearing a regional film.

Nipun Saxena, a Supreme Court advocate, told India Legal: “If the body is to discharge an important public function (such as certification of films) the body must be fair, transparent and accountable. Though there are no specific guidelines laid down entailing the qualifications to be eligible to become a member as well as the chairperson of the Board either in the Cinematograph Act, 1952, or the Rules of 1983, what appears to be more astounding is that the member so appointed shall continue to remain in the Board ‘at the pleasure of the central government’. If there is no time specified as to how long they may continue, this will lead to a situation where the Board may function in perpetuity and the office holders will continue to serve at the ‘pleasure of the government’ ad infinitum.”

He added that the Supreme Court must take a decision that will ensure that the body is transparent and not reduced to being a mouthpiece of the government of the day which has constituted it. “The guidelines could entail that there must not be a political appointment, that the person to be appointed must be a person from the movie fraternity (and preferably a former movie producer/director who would be better placed to understand the concerns of the stakeholders), and the members must have representation from those who have expertise in the field of media and press, law, civil society, the film industry, officers of the central government, so that the decision to be taken can be just and reasonable and after duly consulting experts from every domain,” he said.

India is the envy of the world for its soft power, which includes films which are now afforded global release—Padmavati, for instance, was cleared for release in the United Kingdom a month ago—but thanks to the censors and politically motivated pressures, artistic freedom has been taking a battering of late. Which is why the outcome of Palekar’s petition in the top court will be as eagerly awaited as the release of Pad Man on Republic Day.