When I read Nobel Laureate Albert Camus’ “The Plague” as a teenager, I shivered all the way through it. But when I put it down, I was relieved that I had returned to my own world and my own planet, far removed from the black death that had ravaged Camus’ city of Oran, destroying its health, wealth, political and social culture and systems. The infallible human spirit came to the point of total surrender, but survived tenaciously in pockets of resistance, as mortals stared at the absurdity of their lives and support systems as the relentless, unforgiving scourge decimated them ruthlessly, indiscriminately.

Camus’ “Plague”, (La Peste), having cut a swath of death and destruction, vanished as suddenly as it had arrived. Today, as Covid-19 levels and unites the world, and hospital beds overflow with patients, Camus’ 1947 novel has become a best-seller again. Re-reading it as I sit in my lockdown study in a New Delhi suburb is a surreal experience as I return to that planet where Camus took me as a teenager.

Camus’ Peste of yesteryear, even though its bloodlust may have been far more voracious than Covid’s, is today’s Oranian nightmare and seems indistinguishable from the government announcements now reshaping our lives.

It was not by sheer coincidence that while planning this issue of India Legal under long-distance, stringent “stay-at-home” quarantine-like conditions, almost all the stories we planned or were submitted to us by our contributing editors led, like the Roads to Rome, to Covid.

The judiciary and the legal system which are the focus and raison d’etre for our weekly magazine, have also come heavily under the all-enveloping wrap of Covid’s dark embrace. Our cover story, written by the inimitable juridical scholar, Prof Upendra Baxi, is a forceful and compelling insight into jurisprudential dangers against which civil society and, indeed judges and lawyers, must arm themselves with caveats and checks and balances lest the very rule of law should collapse permanently under the weight of Covid-protection diktats and fiats of administrators and apparatchiks.

That Baxi has penned his thoughts and warnings, albeit in careful and conscientious prose, is a marvellous tribute to the still-flourishing spirit of intellectual inquiry and reasoning which are powerfully contrapuntal to the ideology and the brute strength of “The Plague”.

He writes, for example, that the intense juristic and judicial discourse around the Indian combat against Covid-19 places legal researchers also among the frontline of combatants against a sinister global pandemic. There appears to be a general consensus on the need for vast executive powers to fight this new menace. But equally, the implementation of the current lockdown raises many questions, especially concerning the dignity, livelihood and freedom costs for the impoverished strata (including necessitous migrants) which have been marred by some practices of the pedagogies of violence and inhuman cruelty.

He asks: “Are these expressive of the ‘cavalier attitude towards the intersection of pandemics and mass incarceration’? Such questions raise all over again, the haunting qualities of fiat justitia and salus populi maxims in a Covid-19 world—now infested with new summoning urgencies.”

I fully agree with author and journalist Liesle Schillinger’s recent essay that if you read “The Plague” long ago, perhaps for a college class, “you likely were struck most by the physical torments that Camus’s narrator dispassionately but viscerally describes. Perhaps you paid more attention to the buboes and the lime pits than to the narrator’s depiction of the ‘hectic exaltation’ of the ordinary people trapped in the epidemic’s bubble, who fought their sense of isolation by dressing up, strolling aimlessly along Oran’s boulevards; and splashing out at restaurants, poised to flee should a fellow diner fall ill, caught up in ‘the frantic desire for life that thrives in the heart of every great calamity’: the comfort of community. The townspeople of Oran did not have the recourse that today’s global citizens have, in whatever town: to seek community in virtual reality. As the present pandemic settles in and lingers in this digital age, it applies a vivid new filter to Camus’s acute vision of the emotional backdrop of contagion.”

But there’s much more than just an emotional quotient to the contagion. We may overcome the disease. But what about the poisonous fallout on the social contracts and arrangements through which we create humanism as we now know it, which may outlast the pandemic?

In another recent brilliant commentary on Camus, Matthew Sharpe, Professor of Philosophy at Deakin University, writes that arguably the most telling passages in “The Plague” today are Camus’ beautifully crafted meditative observations of the social and psychological effects of the epidemic on the townspeople.

“Epidemics make exiles of people in their own countries, our narrator stresses. Separation, isolation, loneliness, boredom and repetition become the shared fate of all…. Places of worship go empty. Funerals are banned for fear of contagion. The living can no longer live…”

Camus’ enigmatic character Tarrou identifies the plague with people’s propensity to rationalise killing others for philosophical, religious or ideological causes. It is with this sense of plague in mind that the final words of the novel warn:

That the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.

As Sharpe puts it, there is nevertheless truth in the description of Camus’ masterwork as a sermon of hope. In the end, the plague dissipates as unaccountably as it had begun. Quarantine is lifted. Oran’s gates are reopened. Families and lovers reunite. The chronicle closes amid scenes of festival and jubilation.

Camus’ narrator concludes that confronting the plague has taught him that, for all of the horrors he has witnessed, “there are more things to admire in men than to despise”.

Unlike some philosophers, Camus became increasingly sceptical about glorious ideals of superhumanity, heroism or sainthood, writes Sharpe. “It is the capacity of ordinary people to do extraordinary things that The Plague lauds. ‘There’s one thing I must tell you,’ Dr Rieux the protagonist, at one point specifies:

“There’s no question of heroism in all this. It’s a matter of common decency. That’s an idea which may make some people smile, but the only means of fighting a plague is common decency.

“It is such ordinary virtue, people each doing what they can to serve and look after each other, that Camus’ novel suggests alone preserves peoples from the worst ravages of epidemics, whether visited upon them by natural causes or tyrannical governments.

“It is therefore worth underlining that the unheroic heroes of Camus’ novel are people we call healthcare workers. Men and women, in many cases volunteers, who despite great risks step up, simply because ‘plague is here and we’ve got to make a stand’.

“It is also to these people’s examples, The Plague suggests, that we should look when we consider what kind of world we want to rebuild after the gates of our cities are again thrown open and COVID-19 has become a troubled memory.”

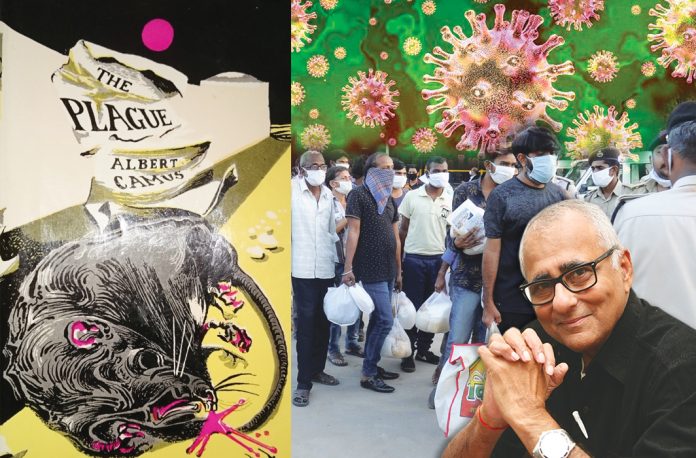

Lead picture: (Illustration of “The Plague”): annabookbel.net