By Inderjit Badhwar

Shortly after a special CBI court acquitted all the surviving 32 accused in the Babri Masjid demolition case last week, several journalists and academicians reminded me of an essay I had written for India Legal magazine in December 2017 which possibly has more relevance today than the time it was written. This was two years before the November 2019 Supreme Court ruling granting the disputed territory to the pro-Ram Mandir protagonists and the recent decision of the CBI court.

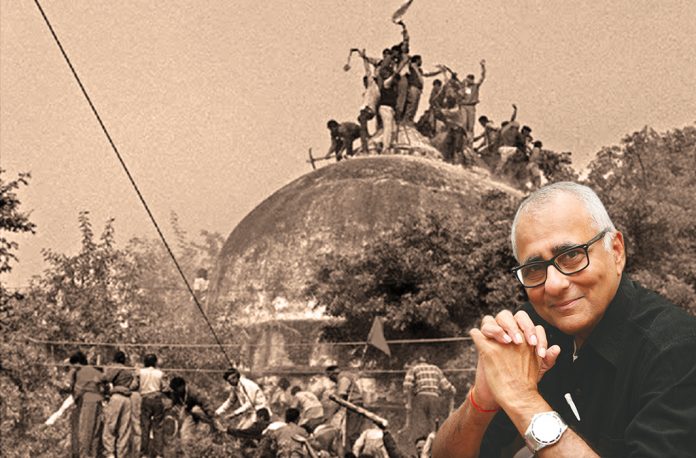

The article my readers were alluding to recalled my meeting with a brilliant young BJP leader, then a close friend, over a quarter of a century ago, shortly before the Sangh Parivar-led kar sevaks destroyed the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. The youthful BJP lawyer, who went on to become what many considered to be one of the most powerful persons in the Narendra Modi government after it came to power, told me privately that he had been struggling with his conscience over whether Lord Ram should prevail over the Constitution or vice versa.

As an erudite advocate, he was fully cognisant of the tortuous legal tribulations of the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute and appeared convinced that any solution in defiance of established jurisprudence could do fatal harm to the Rule of Law on which the Indian Republic is founded. But as a flag-waving believer in the resurgence of political Hindutva, he was equally convinced that saffron militancy—symbolised by the BJP’s campaign to build the Ram temple where it once allegedly stood before being destroyed by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 16th century—was the only way to restore Hindus’ pride in their own nation.

In that essay, in which I tried to put the whole struggle within the larger perspective of India’s socio-political perspective, I wrote that his was an existential dilemma. Even as people like him struggled with it, thousands of others, plagued with no such angst, decided to take the law into their own hands and destroyed the structure on December 6, 1992. More than 2,000 Indians perished in the riots which erupted after the demolition.

I made the point that the Constitution lived on. Notwithstanding the ascent of BJP governments in the states as well as the centre, no matter how hard they may have tried, the majesty of the law still prevented any group from taking over the disputed site. True, the Kalyan Singh government then in power in UP was unable to keep its oath to the Supreme Court to maintain law and order and communal harmony. This was, indeed, the solemn pledge, given in writing in November 1992, on the basis of which the apex court allowed a symbolic “kar seva”—the performance of rituals by priests and worshippers.

The Supreme Court’s main intention at the time was to ensure that the legal status quo on the land ordered earlier by the Allahabad High Court, pending the outcome of multifarious title suits filed over the disputed plot, should remain inviolable. The rest is history. The old mosque was razed, but in the presence of BJP bigwigs while the police forces watched the show from the sidelines.

The outcome was not only a setback for the Court which had in all earnestness trusted the assurances from the state government but also for Congress Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao who, against the advice of his own intelligence sources, trusted the Sangh Parivar and refused to send central forces to maintain law and order. Thousands of Hindutva revivalists took the law into their own hands and destroyed the historic Babri Masjid.

But had religious identity politics edged out the Constitution? Not yet. True, a huge post-Partition communal divide cut a swath across India. Hindutva became a formidable political force to reckon with. But the law just refused to step aside and surrender the land to those who would try and acquire it through extra-constitutional means for political gain.

Until the Supreme Court’s November 2019 decision, the disputed 2.77 acres remained virtually no man’s land. The case had landed in the Supreme Court in the form of an appeal against a 2010 judgment by the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad High Court outlining a land-sharing formula between Hindus and Muslims.

In the last week of 2017, a controversy had arisen when senior advocate Kapil Sibal argued that the hearing be postponed until after the 2019 elections because the BJP would try and make political capital out of it. The Court did not buy this line and postponed hearings until February 8 of the following year. But whether or not Sibal’s argument held water, the point is that the Ram Mandir issue had again become a volatile electoral issue in the Gujarat elections—as it did during the UP elections—with Yogi Adityanath and Himachal Pradesh politician Anurag Thakur. They appeared to have no existential doubts on this matter—Is Lord Ram above the Constitution? In their view, he clearly is. This is an alternative way of looking at post-Independence India.

But it is not really something new. The question of whether India was to have a Hindu or secular identity was intensely debated before, during and after the Constituent Assembly. In fact, the formidable Bhim Rao Ambedkar, whose name has been invoked during the recent electoral battles, had a point of view which would baffle the BJP, and perhaps the Congress.

While researching the early debates, one thing is amply clear. Hindutva forces cannot lay any claim to him or his ideology. And nor can the Congress assert he was a great Nehru admirer. Here are some typical slices of Ambedkar’s thinking:

On December 13, 1946, when Nehru drafted and moved the resolution regarding the aims and objectives of the Constitution before the Constituent Assembly began its session, Ambedkar stalled him. Why? Because the Muslim League (Pakistan had not yet been formed) had boycotted the assembly. Ambedkar insisted that organisations representing Muslims in India could not be excluded from the process of nation-building.

He said: “The destiny of the country ought to count for everything. It is because I feel that it would be in the interest not only of this Constituent Assembly so that it may function as one whole, so that it may have the reaction of the Muslim League before it proceeds… we must also consider what is going to happen with regard to the future, if we act precipitately. I do not know what plans Congress Party, which holds this House in its possession, has in its mind? I have no power of divination to know what they are thinking about. What are their tactics, what is their strategy, I do not know. But applying my mind as an outsider to the issue that has arisen, it seems to me there are only three ways by which the future will be decided. Either there shall have to be surrender by the one party to the wishes of the other—that is one way. The other way would be what I call a negotiated peace and the third way would be open war. Sir, I have been hearing from certain members of the Constituent Assembly that they are prepared to go to war. I must confess that I am appalled at the ideal that anybody in this country should think of solving the political problems of this country by this method.”

He intoned: “If there is anybody who has in his mind the project of solving the Hindu-Muslim problem by force, which is another name of solving it by war in order that the Muslims may be subjugated and made to surrender to the constitution that might be prepared without their consent, this country would be involved in perpetually conquering them. The conquest would not be once and forever. I do not wish to take more time than I have taken and I will conclude by again referring to (Edmund) Burke. Burke has said somewhere that it is easy to give power, it is difficult to give wisdom. Let us prove by our conduct that if this Assembly has arrogated to itself governing powers it is prepared to exercise them with wisdom. That is the only way by which we can carry with us all sections of the country. There is no other way that can lead us to unity. Let us have no doubt on that point.”

Again from a later debate on pluralism: “To diehards who have developed a kind of fanaticism against minority protection I would like to say two things. One is that minorities are an explosive force which, if it erupts, can blow up the whole fabric of the state. The history of Europe bears ample of appalling testimony to this fact. The other is that the minorities in India have placed their existence in the hands of the majority. In the history of negotiations for preventing the partition of Ireland, Redmond said to Carson, ‘Ask for any safeguard you like for the Protestant minority but let us have a United Ireland.’ Carson’s reply was, ‘Damn your safeguards, we don’t want to be ruled by you.’ No minority in India has taken this stand. They have loyally accepted the rule of majority and not political majority. It is for majority to realise its duty not to discriminate against minorities. Whether the minorities will continue or vanish must depend upon this habit of the majority. The moment the majority loses the habit of discriminating against the minority, the minorities can have no ground to exist.”

Another notable Founding Father, HV Kamath, a former ICS officer who belonged to the Forward Bloc, made this redoubtable statement during the debates on pluralism, that current netas would do just as well to remember and quote from:

“I need only observe that the history of Europe and of England during the middle ages, the bloody history of those ages bears witness to the pernicious effects that flowed from the union of Church and State. It is true enough that in India during the reign of Asoka, when the State identified itself with a particular religion, that is, Buddhism, there was no ‘civil’ strife, but you will have to remember that at that time in India, there was only one other religion and that was Hinduism. Personally, I believe that because Asoka adopted Buddhism as the State religion, there developed some sort of internecine feud between the Hindus and Buddhists, which ultimately led to the overthrow and the banishment of Buddhism from India. Therefore, it is clear to my mind that if a State identifies itself with any particular religion, there will be rift within the State. After all, the State represents all the people who live within its territories, and, therefore, it cannot afford to identify itself with the religion of any particular section of the population.

“But, Sir, let me not be misunderstood. When I say that a State should not identify itself with any particular religion, I do not mean to say that a State should be anti-religious or irreligious. We have certainly declared that India would be a secular State. But to my mind a secular state is neither a God-less State nor an irreligious nor an anti-religious State. Now, Sir, coming to the real meaning of this word ‘religion’, I assert that ‘Dharma’ in the most comprehensive sense should be interpreted to mean the true values of religion or of the spirit. ‘Dharma’, which we have adopted in the crest or the seal of our Constituent Assembly and which you will find on the printed proceedings of our debates. That ‘Dharma’, Sir, must be our religion. ‘Dharma’ of which the poet has said: ‘Yenedam dharyate jagat (that by which this world is supported).’”

I think my lawyer friend—the late and deeply mourned Arun Jaitley—quoted in the first para of this essay, may have solved his existential dilemma by heeding these last words.