By Prof (Dr) S Surya Prakash

The bloodbath, marked by a confrontation with Islamabad, reflects the Baloch struggle for existence and survival against the exploitation of their resources by the Punjabi-dominated Pakistani government. Balochistan has been under the jackboots of the Pakistani state for 75 years, with mounting oppression only intensifying the flames of Baloch nationalism.

Balochistan has seen periods of active rebellion for independence from Pakistan. It was the betrayal and merger of Kalat, a princely state in what is now Balochistan, into Pakistan by Muhammad Ali Jinnah that was one of the causes of the fierce battle for independence by the Baloch people. It was the betrayal of the Baloch people by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, that is at the root of the insurgency. The people of Balochistan which is an arid but mineral-rich province, have historically felt ignored by the Punjab-dominated politics of Pakistan.

The Khan Of Kalat

The Khan of Kalat had in 1946 appointed Muhammad Ali Jinnah as his legal advisor to represent his case before the British Crown. In a meeting in Delhi on August 4, 1947, attended by Lord Mountbatten, the Khan of Kalat, Jawaharlal Nehru and Jinnah supported the Khan’s decision for independence. On Jinnah’s insistence, Kharan and Las Bela were to be merged with Kalat to form a complete Balochistan. So, after being independent for 226 days, Balochistan was invaded and merged into Pakistan, not with the will of the people, but by Jinnah’s betrayal and Islamabad’s military might. This betrayal from 75 years ago and the exploitation of the people and the region’s resources remain at the root of the Baloch people’s armed resistance.

Today’s crisis in Balochistan is the outcome of decades of state misrule, economic neglect and the denial of fundamental rights. The ongoing insurgency, the fifth since 1948, involves Baloch nationalists fighting against the Pakistani state. Balochistan has experienced violent independence movements in 1958-59, 1962-63, 1973-77, and the most recent has been ongoing since 2003. The brutal elimination of popular Baloch leaders Nawab Akbar Bugti has added fuel to the fire in the deprived province of Balochistan.

The crackdown on peaceful protesters has sent a chilling message, especially to the youth, who now believe that even non-violent demands for justice are met with repression. This has reinforced the narrative that the state is not interested in dialogue.

Every insurgency/freedom movement was ruthlessly crushed by the Punjabi-dominated Pakistani army. The forceful disappearance of young Balochis, rape, torture and murder of innocent has become order of the day. The ambitious CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) project did not provide either employment to the people of Balochistan or development of Balochistan. The Baloch people’s corridor that the CPEC is meant to exploit the minerals and natural resources for the development of the Punjab, even Gwadar Port didn’t bring any change in the lives of people. The highways and the ports constructed by the Chinese irritated the people of Balochistan against the Chinese engineers and workers.

The Erosion Of Legitimacy

The present situation of Balochistan was aptly described by Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s ambassador to USA, UK and UN that the use of coercive power in a political vacuum with unrepresentative provincial governments in place—including the present one—has meant state actions have lacked the authority and legitimacy needed to elicit public support. Legitimacy, after all, is built by meeting people’s needs and aspirations. Long-festering, unfulfilled demands of Baloch groups and citizens, such as those concerning missing persons, have deepened the sense of public alienation. In such a climate, the deployment of hard power has repeatedly proven to be counterproductive.

The recent crackdown on the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC) and the arrest of its leaders and human rights activists have further inflamed an already volatile situation. Rather than quelling unrest, such heavy-handedness risks further radicalizing opinion in the province. A particularly provocative move was forcibly preventing a protest march to Quetta led by former chief minister and leader of the Balochistan National Party, Akhtar Mengal, aimed at pressing for the release of detainees.

According to a BYC spokesperson, police baton-charged peaceful protesters, injuring two women and arresting several individuals. Ultimately, the sheer volume of protesters overwhelmed the authorities, enabling access to the morgue. Such moments starkly highlight the distance between the state’s actions and the people’s grievances.

The provincial government appears to be losing its writ rapidly. JUI-F lawmaker and former home minister Mir Zafar Ullah Zehri has openly admitted this in the assembly, pointing to the free movement of militant leaders such as Dr Allah Nazar and Bashir Zeb in multiple districts. The administration’s weakening control was underscored when relatives of missing persons, after being denied access for days, managed to take bodies from the Civil Hospital morgue in Quetta despite police resistance.

A Dire Human Rights Situation

The Pakistan Supreme Court Bar Association President, Mian Muhammad Rauf Atta, has described the situation as dire. He pointed out that fundamental rights—enshrined in Articles 9 (Security of Person), 15 (Freedom of Movement), 16 (Freedom of Assembly), and 19 (Freedom of Speech) of the Constitution—are practically non-existent in Balochistan. Regular road closures and mobile network shutdowns only deepens the crisis.

The situation on the ground remains explosive. According to the Pak Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS), terrorism-related deaths in February surged by 73 percent compared to the previous month, with Balochistan accounting for 62 percent of the casualties. This data speaks volumes about the province’s deteriorating security landscape.

Today, life in Balochistan has come to a standstill. Protesters have blocked highways linking the province to the rest of the country and Quetta itself is under a virtual lockdown. Meanwhile, political leaders like Akhtar Mengal, once seen as a bridge between the alienated populace and the state, are disillusioned with the political process. Mengal’s resignation from the National Assembly due to government apathy has only added fuel to the fire.

Mengal is now leading a “long march” against the arrest of BYC leaders, a protest that has been joined by other nationalist groups and mainstream political parties. This growing unrest has pushed many Baloch youth towards supporting groups seeking independence, a troubling trend that could render traditional nationalist parties obsolete.

Militant attacks are increasing in scale and frequency. Up to 20 districts are affected by political unrest and insurgency. Recent high-profile attacks, including the hijacking of a passenger train and coordinated terrorist strikes, demonstrate the growing capabilities of insurgents.

A Feminist Front For Resistance

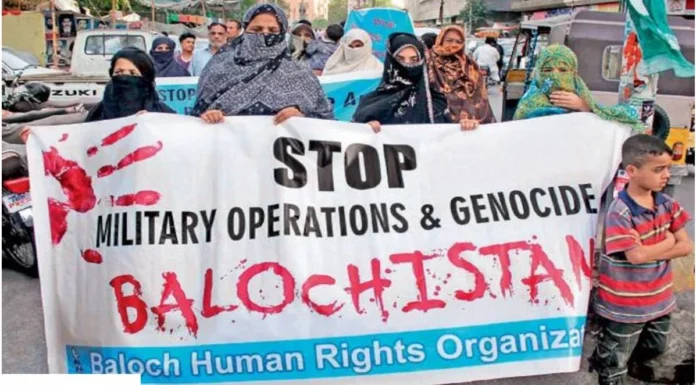

As men are brutalized and disappearances are common, Baloch women are at the forefront questioning the government to show their family members forcibly taken away by the army. The peaceful protest marches, peaceful dharnas, are frequently led by women.

There have also been several cases of women suicide bombers targeting security forces. Women leaders like Dr Mahrang Baloch, an MBBS doctor and human rights activist who lost her father and brother in the movement, have emerged as prominent figures in the rights movement, with many activists having personal stories of state oppression and loss.

New voices like Dr Shaale Baloch have emerged from within the province’s most neglected regions. With a medical degree and a deep personal history of loss and repression, she has become a leading figure in the Baloch Women Forum. Along with Dr Mahrang and Sammi, she symbolizes a rising tide of women-led movements that have filled the vacuum left by traditional parties.

These leaders command immense influence and are able to mobilize large crowds within hours, reflecting the public’s growing trust in grassroots activism. As Sadia Baloch from Quetta remarks, traditional parties have failed the people, and the new generation is reclaiming space through peaceful movements like BYC and BWF.

The sit-in movement, which began in December 2023 amid freezing weather, concluded with the protesters facing harassment, police charges and a sustained media campaign against them. Caretaker Prime Minister Anwarul Haq Kakar continuously accused the families of missing persons of being “terrorist sympathizers,” further deepening tensions and worsening the long-standing distrust between Islamabad and Balochistan.

Dr Mahrang’s return to Quetta told a different story. Thousands gathered to welcome her, with supporters presenting her with pearls and the Balochi turban, a traditional symbol of great respect. Musicians and poets dedicated songs to her, with some even referring to her as “The Sardar of the Baloch”—a title traditionally reserved for male tribal leaders. Ironically, the state’s heavy-handed approach in Islamabad had elevated her status, transforming her into a fiery young leader who was seen as unafraid to challenge the powerful.

The Saga Of Resistance Continues

In March, the BLA attacked the Gwadar Port Authority—a critical node in CPEC—underscoring the growing threat to national economic interests. And on August 26, the insurgency reached a flashpoint with coordinated attacks in 11 districts, killing 72 people. These attacks marked a symbolic remembrance of Nawab Akbar Bugti’s death and highlighted the scale of resistance.

The BLA’s increasing use of suicide bombings, especially by women, is a disturbing evolution. Attacks on civilian targets, especially Punjabis, are on the rise, reflecting a shift in tactics. According to official data, 56 percent of attacks in Balochistan target civilians.

The crisis has also spilled into neighbouring Iran, indicating its growing geopolitical dimension. The fragile security of the region demands urgent attention.

The unrest is not confined within Pakistan. A January attack in Iran’s Sistan-Baluchestan province killed nine Pakistani workers, and subsequent cross-border attacks show the wider regional implications.

Recognition for these activists has come at a cost. Dr Mahrang faces charges of sedition, yet was named one of the BBC’s 100 most influential women of 2024. Today Dr Mahrang is behind the bars and people of Balochistan are protesting for her release. Her rise, like that of others, shows that hope persists even in the bleakest of landscapes.

What happens next in Balochistan will depend on whether the state chooses continued coercion or begins to engage with its citizens with empathy and justice. One can only hope for the latter, if not a new nation, Balochistan may emerge in the near future.

—The writer is Vice-Chancellor, National Law Institute University, Bhopal