By Inderjit Badhwar

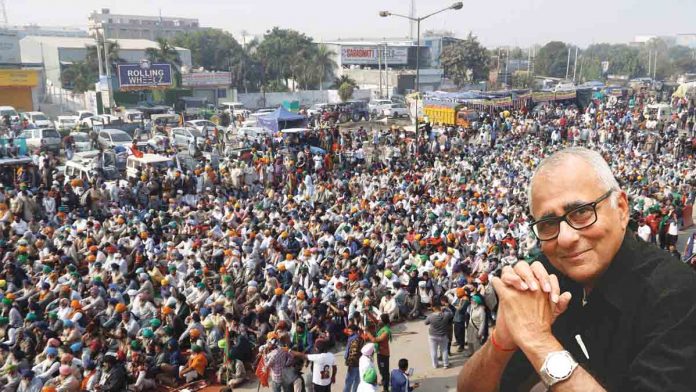

When I started penning this week’s editorial on the surging farmers’ agitation sweeping across the land, I had an eerie feeling that I had encountered the words and phrases and analytical flourishes bubbling inside my head somewhere before and not that long ago.

And as I pored over research material at my disposal, I uncovered the reason for my deja vu. It was an article I had written exactly two years ago (December 2018). I rubbed my eyes as I re-read it. Nothing had changed! I could easily reproduce the piece with the current date and you would not know that it was written two years back (except for the mention of some by-elections that were held in that period).

I believe that this is empirical proof of the adage that those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it. And as our political leaders repeat the past, I think it worthwhile to repeat that December 1, 2018, article in the hope that it still serves as a guide to understanding and finding solutions to the agrarian crisis plaguing this land. Here it is…Flashback 2018:

Even as this is being written, countless thousands of farmers who have converged on Delhi from all across the country are marching to Parliament. They are demanding a joint session of Parliament to acknowledge the ballooning agrarian catastrophe, the implementation of the MS Swaminathan Commission report, increased minimum support prices and the passing of the Farmers’ Freedom from Indebtedness Bill, 2018, and Farmers’ Right to Guaranteed Remunerative Minimum Support Prices for Agricultural Commodities Bill, 2018. These bills were tabled in the Lok Sabha in August by Hatkanangale MP Raju Shetti, the leader of the Swabhimani Paksha, an independent farmers’ political party in Maharashtra. The umbrella organisation for the farmers rally is the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, a union of roughly 200 farmer groups.

A similar, unprecedented farmers’ march took place earlier this year in Maharashtra when they trekked to Mumbai to demonstrate their growing economic misery. Couldn’t the government sense that a massive crisis was at hand and address it head-on instead of talking about bullet trains and sea planes and “collusion with Pakistan”? Shortly afterwards, in June 2018, the BJP received a political drubbing in the bypolls across India.

A day after the results poured in, The Indian Express carried two headlines on its front page: “Opposition Parties Take 11 of 14 Assembly and Lok Sabha Seats”. Side by side, it ran a feel-good headline for the ruling party: “Good Rabi Crop, Uptick in Factory Output Lift GDP up to 7.7 Per Cent”.

It made no sense whatsoever. How could the economy be growing at about the fastest rate in the world while the government receives a simultaneous thrashing at the hands of voters in what could be a prelude to the 2019 general election? In Kairana, UP, which had become the riot-torn crucible for vote-catching Hindu-Muslim politics following bloody communal clashes and a religion-based exodus of population that swept the BJP and its majoritarian sabre-rattlers into power, “Jats and Muslims stepped over riot faultlines to vote together”, the Express said.

Actually, this is an example of why statistics should be damned, and political parties should be careful of using “surging” GDP and related feel-good econometrics as vote-catching electoral propaganda. It just doesn’t work. And history seems to be repeating itself. Even as assembly elections are nearing completion in five crucial states and farmers are converging on Delhi, the ruling party is playing roulette with GDP figures, re-naming cities which have Muslim-sounding names, erecting statues, playing dirty politics with the CBI and trying to revive passions over building a Ram temple in Ayodhya.

When a voter is unemployed, his pockets empty, jobs shrinking, diesel and petrol prices skyrocketing, mandis in distress, prices soaring, GST raising the cost of anything you touch, markets shrinking and uncountable jobs sacrificed at the altar of economic adventurism like demonetisation which failed to distinguish between a “black economy” and a cash-based economy, he’s going to punch you right in the nose when you tell him you stand for the farmer and the working man.

After BJP’s debacles in the June bypolls, I wrote that glib national TV commentators and their talk show guests had suddenly awoken to what they called “farmers’ issues” as being important to the elections. The wisdom of morons! Actually, like the economy, it IS the farmers, Stupid! Their “distress” is the country’s distress—yours and mine. These folks are not just another wrapped item in your shopping basket of goodies. They ARE the issue, and they are the force that combined under common banners cutting across caste and religious divides to march on Delhi.

They are not “playing victim” as some would have us believe. According to Sujan Hajra, chief economist at Anand Rathi, a financial analysis firm, India has one of the world’s highest food spoilage rates; one of the world’s lowest per capita productivities and farmer incomes; poor rural roads affecting timely supply of inputs and transfer of outputs; inadequate irrigation systems; poor seed quality; inefficient farming practices; harvest spoilage causing over 30 percent of wastage and lack of organised retail and competing buyers.

Their grievances cut across identity lines—no returns on investment, loans they couldn’t repay, inadequate support prices, unrequited money from the sales of their cane, suicides and their kids dying in hospitals because of lack of oxygen.

Farmers are part of India’s large unorganised sector. (There is abysmally low productivity in the farm quarter—50 percent workforce and just 16 percent GDP.) As Professor Arun Kumar, one of India’s best known international economists, notes, this (total unorganised sector) is 93 percent of total employment and 45 percent of total output. Data for this sector is not available in the routine because it is dispersed across the length and breadth of the country in tens of millions of small and cottage units which do not report their data to any agency. The largest component of the unorganised sector is agriculture, constituting 45 percent of the workforce and 14 percent of the total output of the economy. Data for agriculture is collected for each of the growing seasons and becomes available with a short time lag, but it is not collected for each quarter.

The non-agriculture part of the unorganised sector constitutes 48 percent of the workforce and 31 percent of the total output. It is the data for this part that is not available for some years, Professor Kumar explains. One of the top demands of the farmers who marched to Parliament last week is implementation of the Swaminathan report. As one of the organisers told Scroll in a recent interview: “If they {the BJP} lose elections in all five states, then they will surely implement it,” (referring to the ongoing assembly polls in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Telangana and Mizoram).

Every Indian needs periodically to be reminded of just who Swaminathan is. After India became an independent nation in 1947, the highest import bill for the country was food grains. Late into the 1960s, India used to spend as much as Rs 700 crore (a massive sum given exchange rates of those years and virtually no foreign exchange surpluses) only on import of food grains, this being the single largest outgo on foreign exchange.

Enter Swaminathan, or “MS”, as his friends called him. This genius—and agricultural scientist—wrought a virtual miracle called the “Green Revolution” by introducing high-yielding varieties of seeds which doubled and tripled and quadrupled production. “Basket case” India was soon to be transformed into a surplus country.

From 1972 to 1979, he was director-general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research. He was principal secretary, Ministry of Agriculture, from 1979 to 1980. He served as director-general of the International Rice Research Institute (1982-88) and became president of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources in 1988.

In 1999, Time magazine placed him in the “Time 20” list of most influential Asian people of the 20th century. The reason for the revival of his name today on the roads of rural India and in farmers’ marches in Mumbai and Delhi is that despite the Green Revolution in India, he had foreseen an agrarian crisis—“farmers’ distress” as it is popularly called in today’s headlines—many, many moons ago.

He chaired the National Commission on Farmers, and submitted five reports between December 2004 and October 2006. Following from the first four, the final report focussed on causes of farmer distress and the rise in their suicides, and recommended addressing them through a holistic national policy for farmers. The findings and recommendations encompass issues of access to resources and social security entitlements. This was over 12 years ago. And most of what he predicted came true while his recommendations gathered dust! Today, leaders of agitating farmers’ organisations across the country have re-discovered these reports and are demanding execution of their recommendations.

How many people, including bureaucrats in the finance and agriculture ministries, have actually read Swaminathan’s report or are even aware of the contents? For their edification, I reproduce below excerpts of a summary of the report which stressed constantly on modernising farming methods and social protection for landless farmers through greater governmental involvement. Its focus was on faster and more inclusive growth. If only someone had been listening!

The key issues were: A medium-term strategy for food and nutrition security in the country in order to move towards the goal of universal food security over time; enhancing productivity, profitability and sustainability of the major farming systems of the country; policy reforms to substantially increase flow of rural credit to all farmers; special programmes for dryland farming for farmers in arid and semi-arid regions, as well as for farmers in hilly and coastal areas; enhancing the quality and cost competitiveness of farm commodities so as to make them globally competitive; protecting farmers from imports when international prices fall sharply and empowering elected local bodies to effectively conserve and improve the ecological foundations for sustainable agriculture.

More than a dozen years ago, Swaminathan actually used the term “farmers’ distress”. He wrote: “Agrarian distress has led farmers to commit suicide in recent years. The major causes of the agrarian crisis are: unfinished agenda in land reform, quantity and quality of water, technology fatigue, access, adequacy and timeliness of institutional credit, and opportunities for assured and remunerative marketing. Adverse meteorological factors add to these problems.

“Farmers need to have assured access and control over basic resources, which include land, water, bio-resources, credit and insurance, technology and knowledge management and markets. The NCF recommends that ‘Agriculture’ be inserted in the Concurrent List of the Constitution.”

What has now erupted as the most volatile social-economic issue facing the nation has been in the making for decades. Despite more than half of India’s 1.3 billion population making its living from farming, their contribution to the overall economy has been diminishing, notwithstanding increases in output. This actually translates into a full-blown crisis and cannot be dismissed as what TV pundits and glib politicians are calling farmers’ “issues”. A national crisis is not just an “issue” but a cataclysmic phenomenon with drastic political and social consequences in which the very foundation of the economy can be devastated.

Read Also: Future of Legal Education