By Dilip Bobb

Author and journalist Laura Spinney’s gripping narrative titled Pale Rider was written before the current pandemic but has been reprinted by her publishers because of its relevance to the Covid scourge and the many lessons it draws from history. One being that it had an impact on India’s Independence. The highly infectious Spanish flu had swept through the Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat where Gandhi was living, four years after he had returned from South Africa. Gandhi and his associates at the Ashram were lucky to recover. The Spanish flu influenza killed between 17 and 18 million Indians, more than all the casualties in World War I. Yet, what did it have to do with India’s Independence?

In an interview at the time, the author explained: “The devastation wrought by the disease exacerbated social tensions in India, contributing to an eruption of violence and significantly strengthening the Independence movement. By 1918, Mahatma Gandhi was being seen as a future leader of the nation, but he lacked grassroots support. That spring, in Gujarat, he had organised two satyagrahas but these were followed by thousands of people, not hundreds of thousands. When the flu returned that autumn, he fell ill, along with other members of the Independence movement who shared his Ashram. Armistice in World War I was signed in November 1918, but the Rowlatt Act followed in India, which imposed martial law. That led to a call for a satyagraha by a very weak Gandhi, and eventually, the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy. What followed in 1920 was a special session of the Congress in Calcutta, where Gandhi promised self-rule within a year if the Congress followed his satyagraha model all over India. By 1921, thanks in no small part to the freedom fighters who provided relief to millions of Indians during the flu, Gandhi had secured massive grassroots support.” Spinney makes a compelling case for considering Britain’s medical negligence in treating flu in its Indian colony as an eventual catalyst to India’s Independence movement.

When her book first came out, there were some reports in the media on the Gandhi connection but the major relevance to Spinney’s book is the comparisons between the two pandemics and the lessons it offers. Spinney’s research on the 1918 pandemic reveals how the virus travelled rapidly across the globe, exposing humankind’s vulnerability. Like the current pandemic, she says, the Spanish flu dramatically disrupted and often permanently altered—global politics, race relations and family structures, while spurring innovation in medicine and the arts. It also, Spinney says, created the true “lost generation”. We are witnessing that now, with the phrase “lost generation” being frequently used to describe young students whose academic pursuits have been totally disrupted by Covid-19 and its variants along with confirmed cases of mental health issues among adolescents. Schools have been largely shut for the last two years and online learning is proving inaccessible to many while others find its sterile and solitary process mentally destabilising.

The UN estimates that, for the first time in history, about 1.5 billion children were out of school during the pandemic, with at least a third unable to access remote learning. A UNICEF report on the current pandemic says that “the longer the crisis persists, the deeper its impact on children’s education, health, nutrition and well-being. The future of an entire generation is at risk.”

The other significant comparison is that the 1918 pandemic spurred many countries to introduce welfare measures for the poorer sections of society—India has launched many such welfare measures over the past two years.

Like Covid-19, the Spanish Flu was a pandemic of influenza that struck in three waves. Like the Delta variant in the current context, the most deadly during the Spanish flu was the second wave. Also, like Omicron, the third wave during the 1918 pandemic emerged in the early months of the year.

The other, more visible parallel with today, says the author, is based on the fact that pandemics have always gone hand-in-hand with xenophobia. This time, the closing of borders and the entry and exit of passport holders belonging to only specific countries shows that to be true. On May 8, 2020, the United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres said that “the pandemic continues to unleash a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering” and urged governments to “act now to strengthen the immunity of our societies against the virus of hate.” In America and Europe, Asians were targeted, particularly Chinese. Then US President Donald Trump’s frequent use of the term “Chinese virus” and his Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s similar use of “Wuhan virus” only added fuel to the xenophobic fire. In India, discrimination against Muslims escalated after public health authorities identified a Tablighi Jamaat group’s gathering in New Delhi in early March 2020 as a source of spread of Covid-19.

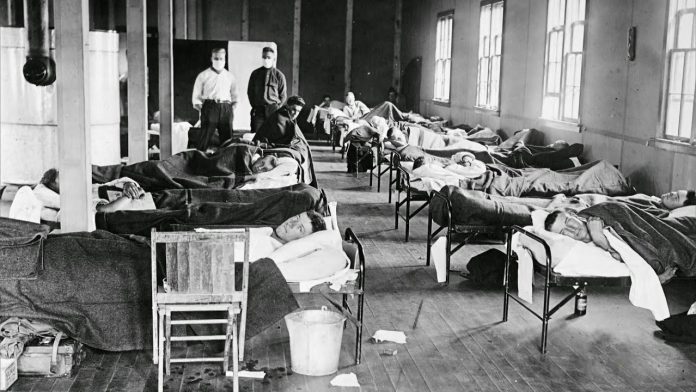

What would be of crucial interest to everyone today was what impact did the 1918 pandemic had on society and the changes it wrought. For one, it gave a big stimulus to the concept of socialized medicine and healthcare. The author says that the baseline health of populations started to become much more transparent, and much more visible. The most obvious impact on society is that inequality increased dramatically. The poorest sections, the most vulnerable, the ones with the least good access to healthcare, the ones who work the longest hours, who live in the most crowded accommodation, were more at risk during the 1918 pandemic, as is the case with the current one. It caused massive disruption to key services and soaring prices. The Spanish flu virus, like its contemporary version, showed a marked propensity to mutate and generate variants and also caused an inflammatory response through the lungs. What is interesting is that the H1N1 flu strain that caused the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was extinct until very recently.

Spinney is a science journalist and in her version we hear stories of how “your best chance of survival was to be utterly selfish and ignore all calls for help.” In what would be familiar to Indian readers, she describes how the 1918 outbreak saw bloated corpses clogging rivers and how smoke blocked out the sunlight for days as the unburied were cremated in huge funeral pyres. Like now, countries attempted a policy of cordon sanitaire, closing their borders as they blamed the virus on others. The other significant comparison is that the Spanish flu outbreak, caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin, started in March 2018 (March 2020 is when the current pandemic started to spread rapidly and the death toll started to rise, leading to lengthy lockdowns). The 1918 pandemic ended towards the end of 2020. The Omicron variant has helped extend the current pandemic pass that end point.

The title of Pale Rider is taken from the apocalyptic “Pale Horse, Pale Rider”, an African-American spiritual in which the rider’s name is Death. We have seen enough of that till now. As of January 31, 2022, between five to six million people have died from the Covid-19 pandemic and we are still astride that Pale Horse.