The Kerala government may have decided not to implement the controversial amendment related to cyberspace, but the debate whether such laws should be the sole prerogative of the centre remains alive.

By Na Vijayashankar

When Section 66A of the Information Technology Act (ITA) 2000/8 was scrapped by the Supreme Court in 2015, most people hailed the decision as a torchbearer of the freedom of speech. Many, however, felt that the top court had erred in not distinguishing between “publishing” and “messaging” and also not reading down the Section instead of scrapping it altogether along with provisions related to spamming, cyber stalking, cyber bullying, cyber extortion and cyber harassment.

Since then, the central government has not come up with an alternative to Section 66A and only tried to tinker with the intermediary guidelines in a half-hearted manner. Hence, fake news and cyber defamation continue without appropriate controlling measures under ITA 2000.

The inability of the central government to come up with an alternative to Section 66A since 2015, when the judgment was pronounced, led to a situation where the Kerala government had to come up with an ordinance under the State Police Act which challenged both the Supreme Court as well as the central government’s powers and intentions to regulate cyberspace.

However, later, after facing a barrage of criticism from across the political spectrum, including the LDF alliance, on the ordinance, the Chief Minister of Kerala, Pinarayi Vijayan, announced that the provisions of the ordinance will not be implemented. Later, the Kerala government also decided to bring an ordinance to withdraw the controversial amendment.

The U-turn taken by the state government on the ordinance does not in any way lay to rest a debate on the issue that cyber legislation is the sole domain of the central government and there is a need for a law on cyberspace.

Section 90 of ITA, 2000, states as follows:

Power of State Government to make rules

(1) The State Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, make rules to carry out the provisions of this Act.

(2) In particular, and without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing power, such rules may provide for all or any of the following matters, namely (a) the electronic form in which filing, issue, grant receipt or payment shall be effected under sub-section (1) of Section 6; (b) for matters specified in sub-section (2) of Section 6

(3) Every rule made by the State Government under this Section shall be laid, as soon as may be after it is made, before each House of the State Legislature where it consists of two Houses, or where such Legislature consists of one House, before that House.

Since ITA 2000 was a central law, it was interpreted that under Section 90, states only have powers to frame rules for implementing the provisions of the law and not to frame new laws themselves.

However, under the argument that “law and order” is a state subject, some states made laws under their police acts applicable to cyber cafes, online gaming, etc. And the trend was extended to the Kerala government’s ordinance related to “publishing of information in electronic form”.

The Kerala ordinance states as follows:

Amendment of Section 118 of Kerala Police At 2011 (8 of 2011)

In the principal Act after Section 118, the following Section shall be inserted namely:

118A: Punishment for making, expressing, publishing or disseminating any matter which is threatening, abusive, humiliating or defamatory:

Whoever makes, expresses, publishes or disseminates through any kind of mode of communication, any matter or subject for threatening, abusing, humiliating or defaming a person or class of persons, knowing it to be false and that causes injury to the mind, reputation, or property of such person or class of persons or any other person in whom they have interest shall on conviction, be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years or with fine which may extend to ten thousand rupees or with both.

It was interpreted that the ordinance was applicable to posts on Twitter or Facebook or other social media. The LDF government reportedly said that this amendment was done to “control cyberbullying”.

One can look at the impact of this ordinance under two assumptions. Firstly, the ordinance used the term “any kind of mode of communication”. This did not specify that “electronic communication” was part of the ordinance. Since legal recognition to electronic document as equivalent to paper document was provided through ITA 2000, which is a central law, and Section 90 of that law restricts the powers of the police to only issue rules for implementing the law as provided therein and not introduce a new penal section with imprisonment etc., it can be argued that the ordinance may not have been applicable for electronic documents.

The legislative intent of the Police Act is also to be considered as restricted to the regulation of police activity and ideally it should refrain from passing a law carrying punishments unless that is related to the prevention of carrying out duties of the police as envisaged under the Act. For example, if the defamation is of a “police officer” and aimed at preventing him from discharging his duties, then the Police Act could be considered as having jurisdiction to make regulations.

But infringing on a central law meant to provide legal recognition to electronic documents and regulate crimes associated with cybercrimes, should be considered as ultra vires the Section 90 of ITA 2000. It is, however, possible that this view may not be acceptable to the majority of legal professionals who may say that “maintenance of law and order” includes regulating cyber activities, and hence, the state government has the power to make laws of this nature.

It is under the assumption that “any mode of communication” may be considered as inclusive of the electronic mode of communication that social media comes into relevance. The clarifications given by the politicians indicated that this law was not meant to regulate the “media” and hence it could have been used only to punish “individual citizens” who express themselves on platforms which are not considered as “social media”.

A doubt that arises is, if Twitter is social media and the Kerala government did not want to apply this law to Twitter, then a contributor to the social media called Twitter may claim to be a “social media journalist” and his publication becomes “social media journalism”. Hence politicians assured that they may not be targeted. However, since nobody believes the politicians, this assurance had no meaning.

The next point to be noted is that the Section was applicable only for posts which are “known to be false”. If the person posting the message did not “know” that it was false but believed that it was “true” or it was in fact “true”, then the Section was not applicable. This means that unless there was prima facie evidence established by the police that the information was “false and the person was aware that it was false”, there was no cause for action under this Section. The Section required “injury to the mind, reputation, or property of such person or class of persons or any other person in whom they have interest”.

It was not clear what is meant by “in whom they have interest”. Perhaps this could be interpreted as that the person who was to be charged should have had an intention to defame a person in whose defamation there must be some interest of the person.

If we presume the Kerala government had the power to make laws covering cyber defamation or cyber bullying as was the scope of Section 66A of ITA 2000, then the amendment was a direct affront to the Supreme Court in the Shreya Singhal judgment.

If the power of the Kerala government was used to bring out this law for punishing use of electronic documents as part of an expression of opinion as per the “Freedom of Speech” enshrined in the Constitution, then every state government may make their own Section 66A and later every other Section of Chapter XI of ITA 2000 and create their individual versions of ITA 2000. This will lead to a chaotic situation and breaking the structure of the Union of India.

In order to ensure that ITA 2000 remains the only law for regulating electronic documents, it is necessary for the government to recognise that “cyber space” is a different jurisdiction which should not be considered as belonging to a “state”. It should be always at the Union level. Hence, cyber laws should belong to the central government. The implementation can be delegated to the local police but law making should remain with the centre.

As a further improvement, the implementing police can also be made a “National Unit” and brought directly under the Union government administration so that cyber police will be a national cadre. This will enable building up of better expertise and proper sharing of resources.

If cyber laws are allowed to be created and implemented under local laws of the state or later under municipalities etc., then movement of people within the country would be highly restricted since police in one state will start enforcing their writ in another state and people would not like to travel to a state at which any of their Twitter posts may be found objectionable.

The way police in a state implement the law is best showcased by the Maharashtra Police under the Shiv Sena government and no person will be safe in expressing any opinion which may remotely be objectionable to a politician in a rogue state. The Kerala ordinance should therefore be seen in this context of an effort to create a highly objectionable precedent.

—The writer is a cyber law and techno-legal information security consultant based in Bengaluru

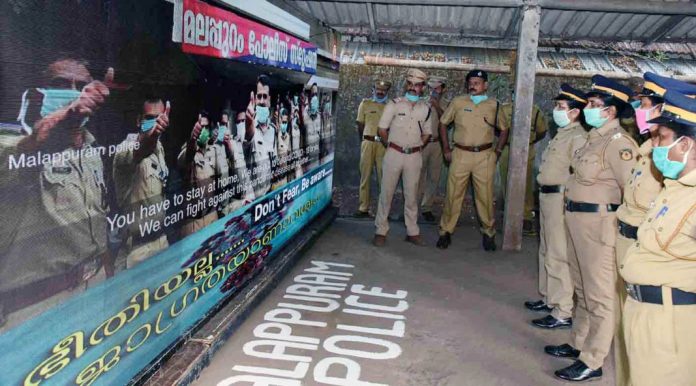

Lead Picture: UNI

Read Also: Supreme Court transfers hawala operator Naresh Jain’s bail plea to Justice Kaul’s court