Kamra is as close as we can get to medieval European court jesters or village fools. By punishing a jester for a joke, we put at risk our right to free speech, sense of humour and right to say what we think needs to be said.

By Jayant Tripathi

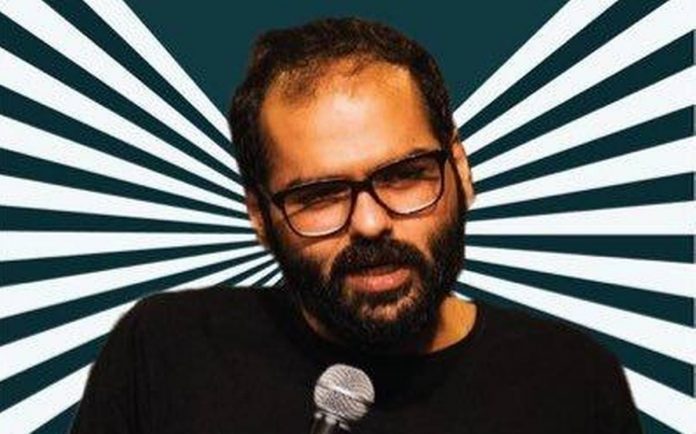

Have Kunal Kamra’s tweets “scandalised” the Supreme Court or “lowered its authority”?

The famous line, often misattributed to Voltaire—I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it has been the aspirational benchmark for the votaries of the absolute right of freedom of speech and expression.

In India, the Constitution provides the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression, but makes that right subject to certain “reasonable restrictions” in relation to, inter alia, contempt of court.

The history of the contempt jurisdiction of courts emanates, in the common law system, from the doctrine of “inherent powers” of the courts. The Contempt of Courts Act of 1921 and the subsequent Act of 1952 did not make any attempt to define what constituted “contempt of court”. It was left to the courts to decide on the basis of common law doctrine of “inherent powers” and judicial precedent, as to what constituted “contempt” and the extent of punishment.

The problem with such an unfettered “inherent” right to punish for acts perceived as contempt is best illustrated in the recent movie “The Trial of the Chicago Seven” — based on real events—where the defendants’ lawyer was sentenced to four years in prison for repeatedly referring to the judge as Mr Hoffman, instead of “Your Honour”.

Perhaps in order to overcome the potential misuse of this unbridled “inherent” power, the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, defined the term. “Civil Contempt” is defined as the wilful and deliberate disobedience of an order of the court, and “criminal contempt” is defined as words or acts that (i) scandalise or lower the authority of any court; or (ii) prejudice or interfere with the due course of any judicial proceeding; or (iii) interfere or obstruct the administration of justice.

Unfortunately, the Act of 1971 fell into the error of using vague and undefined terms to define contempt. The term “scandalise”, as also the term “lowering the authority of the court”, are undefined and amorphous, capable of being interpreted differently by different judges.

Since Kamra’s tweets were not in violation of any court order, and neither prejudice nor interfere with any judicial proceedings nor interfere with or obstruct the administration of justice, the only charge that can possibly stick against him would be that his tweets scandalised the court or lowered its authority.

So how do I know what part of my speech will “scandalise” the court or “lower the authority of the Court”? Can a “Court” be scandalised? Or is it judges who are “scandalised”? And if it is judges, by what yardstick is the level of their outrage to be measured?

In other parts of the world, from where our legal system draws inspiration, the concept of “The Court” getting “scandalised” has been done away with. Justice Felix Frankfurter of the US Supreme Court, speaking of the concept of “scandalizing the Court”, famously said: “Some English judges extended their authority for checking interferences with judicial business actually in hand, to ‘lay by the heel’ those responsible for ‘scandalizing the court’, that is, bringing it into general disrepute. Such foolishness has long since been disavowed in England and has never found lodgment here.” In the UK and US, judges, if defamed, are free to pursue the same remedy as available to an ordinary citizen, and sue for defamation.

As far as lowering the authority is concerned, one can only remember the words of Lord Denning, who said: “Let me say at once that we will never use this jurisdiction as a means to uphold our own dignity. That must rest on surer foundations. Nor will we use it to suppress those who speak against us. We do not fear criticism, nor do we resent it. For there is something far more important at stake. It is no less than freedom of speech itself.”

Kunal Kamra, as a practitioner of observational comedy, is as close as we can get in these modern times to the tradition of medieval European court jesters or village fools. Allowed to say anything they wanted, without fear of repercussions, these jesters and fools sometimes spoke bitter truths disguised as japes. In India, this tradition found expression in stories about Birbal and Tenali Raman.

If the jester spoke the truth, a wise king, recognising the inherent wisdom in the joke, modified his behaviour, and if there was no truth in the joke, then it was just a fool’s jest which was recognised as such.

By punishing a jester for making a joke, however puerile, we put at risk many things—our perspective, our right to free speech, our sense of humour, and most of all, our right to say what we think needs to be said.

—The author is a lawyer practicing in Delhi

Comments are closed.