By Vikram Kilpady

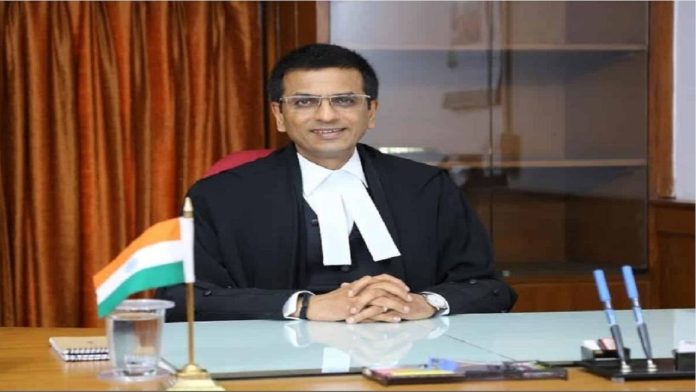

The speeches of judges in and outside courts are notable for observations that are cutting as well as all encompassing. Among the judges of the Supreme Court, Justice DY Chandrachud has maintained a lofty standard for upholding liberty, free speech and the deliverance of bail as soon as possible. This is not to say the other judges don’t; Justice UU Lalit headed the bench which gave permanent medical bail to Telugu revolutionary poet Varavara Rao, accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, but the Harvard-educated Chandrachud weathers the challenges he meets with aplomb. Of course, all caveats against recency bias apply!

In late July, Justice Chandrachud granted bail to AltNews co-founder Mohammed Zubair who had been arrested for offending people with his tweets. Zubair’s 2018 tweet of a sequence from an early 1980s film where a honeymoon hotel segues into a Hanuman Hotel had drawn the ire of the Hindutva-subscribing devout, who saw in it an insult to the God Hanuman. This led to an FIR being lodged against him in Delhi. Other tweets of Zubair saw successive FIRs lodged in five Uttar Pradesh districts. Zubair, who would get bail in one case, would continue to be in jail because he had not got similar relief in the other FIRs.

On his plea in the Supreme Court to club the FIRs together, the bench led by Chandrachud and comprising Justice Surya Kant and Justice AS Bopanna granted him bail, noting the process had itself turned into punishment for those accused. The judges also extended protection to any other FIR that may be lodged against Zubair. While the phrase “the process is the punishment” must already be well known to the many thousand undertrials languishing in the prisons of the country and their families, its utterance by a learned bench pointed to their understanding of the ills plaguing the country’s justice system. After all, who else will have an eagle eye view of violated rights in the face of an aggressive prosecution? Even then, the Zubair order came almost a month after he had been arrested on June 27. We can only tsk-tsk for the others who don’t have heavyweight lawyers and are far from being cause célèbre.

In early August, speaking at the Gujarat National Law University convocation, Justice Chandrachud had more to say. He spoke on how the tolerance of hate speech by a few didn’t amount to not opposing it. In the social media world of paid trolls who don’t bat an eyelid before launching into smears against one’s parents and their presumed reproductive choices, Justice Chandrachud’s statement is important for those who don’t want to get themselves shredded by trolls just for standing up to hate speech.

With vile ideas becoming normalised and seeming now an accepted part of popular parlance, hate speech itself has metastasized into something more than the worst of cancers imaginable. Justice NV Ramana had spoken out against the ills of the social media and the electronic media and their apparent lack of controls.

At the Ahmedabad event, Justice Chandrachud speaking to the assembled law graduates had another mindbender to deliver. He said what is legal may be unjust and what is just may not be always legal. Take a moment to reflect on it. Is there a trick here? Or is it like hearing the one-handed clap of the Zen monk? In an education system besotted by the engineering and medical faculties, the ability to read through and understand what is being said is often compromised. This writer’s initial befuddlement at Section 2(d) of the Indian Contract Act,1872, and its eventual explication by a teacher shines the logic of reason on why intelligent comprehension is a much-neglected skill, lost by many in the pursuit of Maths, Sanskrit and the sciences. Similarly, the death of journalism at the hands of conversational writing, aka that made for TV, will be bemoaned at some future date.

I hope the reader has had the opportunity to ponder over what Justice Chandrachud said about things being legal and not necessarily just. In doing so, he gave the examples of the Supreme Court judgment decriminalizing Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, the long lack of child labour laws and the enforcement, finally, of minimum wages.

The first of the lot revisits the case made against the Victorian reading of sex between consenting adults of the same gender as “unnatural” and its consequent criminalization. As is well known, the apex court struck it down, leaving the exception of the abuse of minors. Paedophilia is an unnatural offence, and its purveyors must be tracked down and brought to book.

The lack of child labour laws and minimum wage statutes go hand in hand. Child labour was justified by those who saw nothing objectionable in minors making matches and fireworks at the expense of their childhood and schooling; without such toil, Deepavali would be incomplete, according to the very many who jump to defend it. There have been many crackdowns on overt cases of such abuse. But hidden child labour continues to thrive on the side because of what some call “Indian realities”, aka caste and widespread extreme poverty, thus implying that the Universal Declaration of Child Rights should pack its bags and take itself back to foreign shores. What exactly are these realities? Not difficult to spot if we take off the green-tinted D&Gs and look at the very many toddlers begging at the traffic lights or helping their parents at the office districts’ many tea shops and one-plate lunch and dinner stalls.

Indian realities is politespeak for indigence, for which the tony Indian citizen has no recourse, but to blame it on the poor and their immense numbers. This Independence Day many of the tony folk queued up to buy the tricolour from, again, poor families selling our flags to make a show of them on Har Ghar Tiranga and on their social media display pictures. A recorded voice had, after all, insisted one to do so on August 15, every time you made a call, enjoining on you to do the DP thing, come on yaar!

India does have laws against child labour, but there is pushback to allow the exploitative practice in pottery, weaving and other native trades and crafts. Like India’s labour laws generally, they too came into effect only after prolonged agitations for them over decades. The trade unions are blamed for the lockout of Bombay’s cotton mills in the 60s although it can never be said what’s wrong in demanding a fair wage from exploiters clad in the garb of employers. That’s a different question, and we might as well show the other cheek.

It is again the correct time to wonder about labour laws which have now been neatly and symmetrically organized into the four labour codes in the hope that labour, the errant child, will not slow down the pace of India’s development. The red flag lies crumpled, the country’s biggest union is a BJP-affiliated one, but there is no room for dialogue. Any agitation is put down with brute force. Now states have legalised 12-hour shifts. Why do we even observe May Day when everything it stood for has been whittled down? The triumph of the working class in enforcing an 8-hour shift marks the first of May as a day celebrated across the world, in capitalist countries, socialist countries and China, which has both cats to catch mice.

Indeed, what is just may not be legal, and what is legal may not be just. Then there’s national security, then there’s public law and order, there’s the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, then there’s the crossed-out Section 124A of the IPC, then there’s the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, then there’s the PMLA. The recent Supreme Court judgment on the PMLA is a stellar example of how that which is legal may not be just. Slamming down the burden of proof on the accused is anything but just, but, hey, it’s legal.

Imagination can hit roadblocks when thinking of things that may be just, but are not legal; the things to which it obviously does not apply are unauthorised extensions of homes onto city pavements or, worse, roads, or illegal posh colonies that evade bulldozers for generations, while frowning at state expenditure over free water and power. Ring a bell? Or several?

—The writer is Editor, IndiaLegalLive.com and APNLive.com