By Inderjit Badhwar

- Rama, Maryada Purushottam, the king of Ayodhya, banished his beloved queen, in whose chastity he had complete faith, simply because his subjects disapproved of taking back a wife who had spent a year in the house of her abductor. The king bowed to the will of the people, though it broke his heart. Was his stand justified?

- Could Manthara be held solely responsible for the banishment of Rama and the subsequent death of Dashratha?

- Was Ahalya an adulteress or victim of sexual assault?

- Did the actions of the serial molester, Ravana, stand legal scrutiny?

- Was Lakshmana, prince of Ayodhya, legally justified in mutilating Surpanakha? Was his elder brother Rama an accomplice in that action?

These and other existential dilemmas and conundrums with which ancient India’s greatest epic are replete—and which it attempts to deal with in its own classic metaphysical idiom as story after story and episode after episode unfold in the telling of this fascinating tale—are now the subject of a new book that attempts to tackle these issues through modern jurisprudential wisdom, practice and convention.

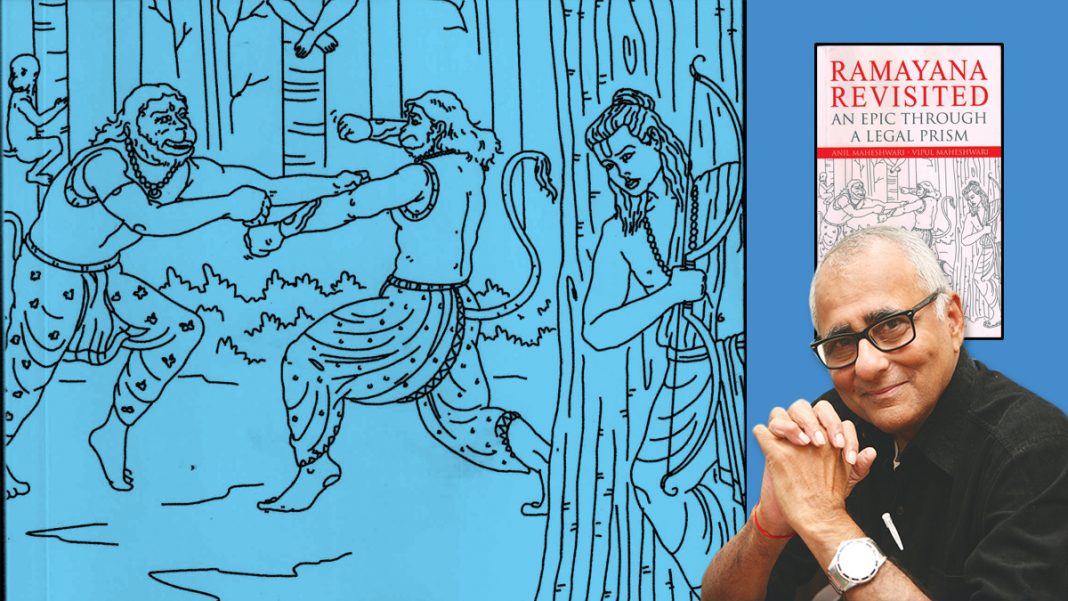

While the idiom remains within the soul and spirit of the Ramayana, the interpretations are modernistic and subjected to the scrutiny of the concepts of natural justice, Roman Jurisprudence, Common Law and the Rule of Law, as these systems have evolved in progressive societies. The book is appropriately called Ramayana Revisited: An Epic Through A Legal Prism. The title was an eye-grabber that drew me into its contents. It is a serious and scholarly piece of work by senior journalist Anil Maheshwari, who retired from the Hindustan Times, and Vipul Maheshwari, a prominent Supreme Court advocate who also served as additional advocate-general of Haryana.

The authors note that the precepts of natural justice and the rule of law were not alien to ancient India where the upholding of dharma was held to be a sacred duty. As the book notes, a king who, after having sworn to safeguard his subjects, failed to protect “should be executed like a mad dog”. Such a provision indicated that sovereignty was based on an implied social contract and that if the king violated the traditional pact, he forfeited his kingship. So a king had to be just as justice trickled down from the crown.

What happens though, the authors ask, if the events of yore are retold and characters made to stand on trial in today’s time? This book is an unprecedented attempt to retell the significant happenings narrated in the Ramayana through the legal prism of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Each chapter comprises a prosecution version, citations of relevant provisions of the IPC, deposition of witnesses and the defence argument. The book jacket notes: “Ramayana Revisited succeeds in bringing all alternative perspectives, leaving the final judgment to the discretion of the reader.”

Read Also: Plea in Supreme Court to transfer all marriage-age petitions to one court

Rather than going into specific details of the book, I will quote selectively from prominent commentators, including the authors, to give the reader a flavour of its contents:

The authors: The specific incidents in the Ramayana, under legal scrutiny as per the modern laws, bring out an infelicitous parallel that the social and political issues remained more or less similar—deceit, conspiracy, jealousy, maternal love, abduction, elopement, rape/incest, censure, position of women (society questioning their chastity), perversion, libel, defamation, the concept of Rama Raj (a welfare state), succession issues, wildlife protection, atrocities against poorer sections of society, exercise of power over righteousness, etc. During the period of the Ramayana, as per the divine theory of kinship (sic), the king was the shadow of God on earth while the IPC works for a democratic set-up in which the people are sovereign.

Justice AK Patnaik, former judge, Supreme Court of India: The vivid description of different scenes and the allegations against various mythological characters show a rare command of the authors on the English language. The manner in which the cases of prosecution and defence are presented display the crafty skills of a lawyer to convince the judge about the innocence or guilt of the different characters.

Vivek K Tankha, Senior Advocate: The Ramayana has always been viewed as a religious epic but (the authors) make you ponder on the legal angles which may be relevant in today’s democratic world. The book is an intelligent amalgamation of Hindu mythology, IPC and relevant court judgments.

Mohan Parasaran, former solicitor-general of India: The innocence or culpability of the persons in the dock has been prudently left to the wisdom of the readers. The act of Lord Rama’s killing of Vali from behind a tree is often portrayed as a stain on his otherwise spotless and virtuous character. I vividly remember one of the greatest acharyas and scholars, Srimad Thirukudanthai Andavan Swamigal, who used to deal with both the viewpoints of King Vali killed by Lord Rama, hiding from a distance. King Vali would put forth several arguments including the violation of the principle of natural justice…He even went to the extent of accusing that it was akin to a false encounter. The Lord countered each of the arguments and being satisfied King Vali surrendered at his feet and attained salvation.

Justice MM Kumar, former chief justice, J&K High Court, Founder-President, NCLT: The nature and function of a judge somewhat brings to mind the day-to-day routine of a sage, as both start living in isolation. Self-imposed limitations bar them from mingling with society so they may live like Caesar’s wife—always above the needle of suspicion. The life journey of a judge resembles that of a sage who is wholly devoted to attaining moksha….The book has presented the prosecution cases responded by the defence, both supported by witnesses against 16 characters of the Ramayana. The statements are an amusing read. The dying declaration of King Dashratha may be relevant against Manthara only to the extent of the last part where the king speaks about her to have equated him with a venomous serpent cradled in her bosom. The case against Manthara is presented in a credible manner to induce redundant damages. I support the idea of the authors to refrain from passing any judgment of conviction or acquittal and leave that aspect to the wisdom of the readers to make up their opinion.