By Inderjit Badhwar

If gender-based glass ceilings are to be smashed, the place to start should be the legal profession. This vital area of human endeavour needs to be exemplary because it has been nurtured and honed by all progressive and dynamic civilisations to monitor, safeguard and promote the lifestreams on which float the multifarious constructs of the rule of law, natural justice, fairness and equity.

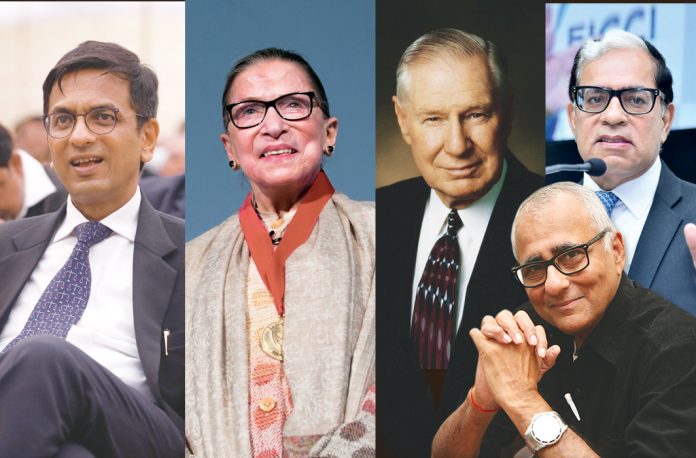

What better way to celebrate the life and compassion of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the iconic US Supreme Court justice who died last week. Albeit, indirectly, Professor Upendra Baxi has done just that in a splendid piece of writing in India Legal, entitled “The Feminization of the Bar”. Baxi reiterates that in the 70 years of the republic, women have made contributions in every walk of life. But the struggle for gender equality and justice continues in the legal profession despite the fundamental right to equality.

I was absolutely delighted that the professor, who not only is a scholar of note but also possesses a flair for inventive authoritative prose, struck forcefully. He writes: “In my last article (September 21, 2020, read here), while counting the number of lawyers, I was surprised to find that in multiple interim orders of a total 18 pages, as many as eight listed the counsel representing parties and these were an overwhelming number of males. I then passingly used the phrase ‘feminization of the Bar’ …The feminisation of the Bar has yet to proceed apace, although we have moved far away from the times when women had to struggle to be counted as ‘persons’.”

Baxi quotes Justice Dhananjaya Chandrachud (in his keynote address at the Harvard Law School Centre on December 11, 2017) that “women in the Indian LP” remained at only five percent compared to “50 percent in Finland, 30 percent in the United States, and generally between 10 percent and 20 percent in Asian countries”. He further continued this sobering tale, writes Baxi, by speaking of “an abysmal 2 percent” of senior advocates being women. Similarly, in “the 63-year-old history of the Supreme Court, out of 204 judges, only five have been women”.

The professor observes that it is not much consolation to know that in 2019, the respective figures were 12 and now two judges (with the recent retirement of Justice Banumathi). There has been no woman chief justice of India. (See Upendra Baxi, “Women in Judiciary: From Raw Deal to New Deal?”, India Legal, November 26, 2018. Read here)

In the March 25, 2019, issue of India Legal, Prof Mohan Gopal authored a profound essay (read here) asking: “Should judges have a feminine approach?” He chose to write on the subject because Supreme Court Justice AK Sikri had raised it during his farewell speech in which he described part of himself as “feminine: …It is the attribute of femininity which instills the desired sensitivity, that is required in varied types of cases and in various circumstances….”

Asked Gopal: What do we make of the significance of Justice Sikri—at his retirement, the third most senior judge in our country—voluntarily claiming the derided and derogatory label of femininity in a misogynist legal profession? Do these remarks, coming from one of India’s most senior and scholarly judges, have any larger significance for gender equality?

“Misogyny” may be too harsh a word, if I may differ with the professor. My choice would have been “male-oriented”, “discriminatory”, perhaps even “patriarchal” or “macho”. But Gopal’s head and heart are affirmatively in the right place as you continue to read his compelling piece.

I was reminded of Ruth Bader Ginsburg who succumbed to a malignancy on the cusp of her 87th birthday, after having lived through and beaten several previous cancers and the attendant debilitating chemotherapy. Until she breathed her last, she continued to be a jurisprudential powerhouse, a role model for judges and students across the world, and a bastion for liberalism and the constitutional value systems of the republic created by America’s founding fathers.

“I will do this job as long as I believe I can do it full steam,” she had remarked after having served her 26th year in the Supreme Court. In fact, Ginsburg is a prime example of the male mindset in the judicial system which is really not that different from other socio-political ecosystems in the world.

To quote from one of the countless biographies of her incredible life, while at Harvard University Law School, the world’s premier law institution, Ginsburg learned to balance life as a mother and her new role as a law student. “She also encountered a very male-dominated, hostile environment, with only eight females in her class of 500.

“The women were chided by the law school’s dean for taking the places of qualified males. But Ruth pressed on and excelled academically,” eventually becoming the first female member of the prestigious legal journal, Harvard Law Review. On June 27, 2010, Ginsburg’s husband, Martin, died of cancer. She described Martin as her biggest booster and “the only young man I dated who cared that I had a brain”.

Some of my favourite quotes from Ginsburg’s thousands of already immortal thoughts on life, society and law include: “If you just needed the skills to pass the bar, two years would be enough. But if you think of law as a learned profession, then a third year is an opportunity, for, on the one hand, public service and practice experience, but on the other, also to take courses that round out the law that you didn’t have time to do.”

“My mother told me to be a lady. And for her that meant, be your own person. Be independent.”

In America, even as older role models like Ginsburg continue as inspirational figures, younger ones exist side by side. One of them is the newly elected firebrand Democrat from New York, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, popularly known by her initials AOC. To quote her: “Mentors of mine were under a big pressure to minimize their femininity to make it. I’m not going to do that. That takes away my power. I’m not going to compromise who I am.”

On the same subject, religious leader, author and lawyer James E Faust who died in 1987 at age 87, once intoned: “Feminity is not just lipstick, stylish hairdos and trendy clothes. It is the divine adornment of humanity. It finds expression in your qualities of your capacity to love, your spiritualities, delicacy, radiance, sensitivity, creativity, charm, graciousness, gentleness, dignity and quiet strength.”

In his article on the subject, Gopal wrote that Justice Sikri was not being “epicene in saying that a part of him is feminine. His purpose in doing so appears to have been to extol four qualities that he considers essential for a judge: sensitivity, mercy, compassion and a sense of justice, a so-called ‘sixth sense.’ Highlighting these values signifies Justice Sikri’s judgement that they are currently in short supply. A corollary of his proposition would be that, in their absence, their antonyms are at large—insensitivity, mercilessness, injustice and cruelty. If true, this would have a deeply corrosive impact on faith and confidence in the Republic itself as well as in our courts.”

Why are these extolled values in short supply? Or are they? Or will the greater “feminisation” of men, an evolution of consciousness as it were, have a practical impact on job discrimination, gender biases, exploitation and the hardships that women as well as men face in everyday life?

Baxi posits: Is it the case that greater women representation on the Bench and the Bar would automatically enhance the quality (and the quantity) of gender justice and equality?

He argues that there is little question that “all women will be one in decrying sex-based violence, degradation and servitude as preventable moral evils and social harm. But not all women share the central tenant of liberal legalism: the complete equality of sexes in all matters of gender justice; their religious faith, for one thing, and their social location on the other lead them to adjust with a lot of subordination inconsistent with the liberal legalist virtues”.

We also learn from experience, Baxi continues, that far from being a war of sexes, “many male justices have engendered legal and constitutional rights and values. Not all males are necessarily patriarchal and contribute a good deal towards women’s emancipation. Only when we recognise the heterogeneity of women and men as moral agents, can we reckon the paradox of why only a handful of women at the Bar, and some progressive Justices, have valiantly paved the way for equality and justice for women, and now for trans-people. Greater representation of women at the Bar and Bench is, of course, essential and must be accelerated; but we ought also to realise that recognising plurality will bring to the table diverse views, and not always the liberal feminist visions of gender justice”.

How then can an “overlapping consensus” (as John Rawls declared) be ensured in severely divided societies, crafting a “reasonable pluralism of rights and justice”, Baxi asks. One answer, he says, is to “return to the basic structure of the Constitution which also includes now Part IV-A. The duties, on the one hand, stress ‘spirit’ of critical enquiry, humanism, social reform, scientific temper and renunciation of all practices ‘derogatory of dignity of women’, and on the other hand, require us all to ‘value and cherish the rich heritage of our composite culture’. Do not these constitutional obligations help us in developing reasonable pluralism?”