While the transfers of High Court judges may be constitutionally permissible, they may not be necessary. Ending transfers of judges will make High Courts judicially strong, effective and independent.

By Justice (retd) Kamaljit Singh Garewal

IN the annals of our judiciary, the period from 1861 to 1919 was one of great changes and colonial expansion. An entirely alien legal system was foisted upon us, giving our traditional laws and panchayati system of justice a quiet burial. Vernacular schools were denied grants while English education was introduced, and schoolboys became anglicised. They would later serve in the lower ranks of the colonial administration.

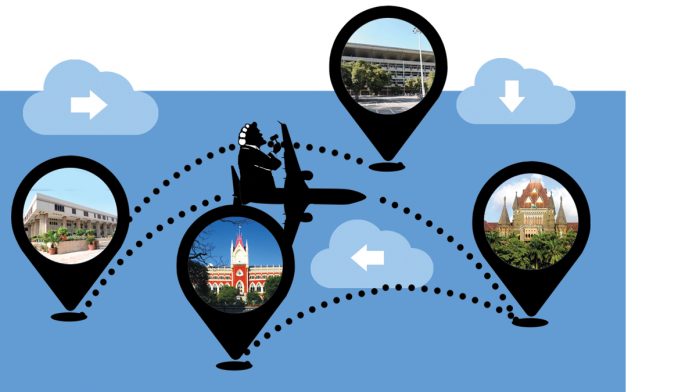

A part of this policy, guided no doubt by Lord Macaulay’s famous minute, was the High Courts Act, 1861. The first three chartered High Courts were set up for the presidencies of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras under Letters Patent granted by Queen Victoria in 1862. This was followed by High Courts at Allahabad (1866), Mysore (1884), Patna (1916) and Lahore 1919 (a few weeks before the Jallianwala atrocity). The Penal Code, the Contract Act, the Evidence Act and the Codes of Civil & Criminal Procedures also come into force in the 1860s.

The Lahore High Court covered the Punjab province from Peshawar to Delhi and beyond. On the day of Independence, East Punjab High Court came up at Simla and assumed jurisdiction over present Punjab, Haryana, Delhi and large parts of present Himachal (except the princely hill states). Later, Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU) High Court got merged with it in 1956. The Court moved to Chandigarh a year earlier. Delhi High Court, a bench of the parent Punjab High Court, separated in 1966, and surprisingly, Himachal right up to Kangra, Kulu, Lahaul and Spiti came under a bench of the Delhi High Court from 1966, till the Himachal Pradesh High Court was created in 1970.

Such have been the constant territorial changes in the region due to partition, merger of PEPSU and the creation of Haryana and the Union Territory of Chandigarh. Resultantly, neither Punjab nor Haryana have their own High Courts on their own territory. It was not so bad for the High Courts of Rajasthan and Orissa which also came up after Independence, but before the promulgation of the Constitution. At that time, there were only 11, now there are 25 High Courts. Even Andhra High Court came up in 1954 at Guntur after the state was separated from Madras. Later, Hyderabad and Andhra were united and Andhra Pradesh High Court was set up at Hyderabad in 1956. Upon re-reorganisation in 2014, the Court was renamed the Telangana High Court, but remained at Hyderabad and the Andhra High Court moved to Amaravati.

The territory of India hasn’t changed except for the inclusion of Goa and Sikkim. But ongoing re-organisations, mergers, and divisions of states have been continuous projects. These steps were mostly to meet regional or linguistic demands or for administrative and political considerations. One just has to spread out the 1950 map of India to see the territories of Part A, B, C and D states. Each part of India was constitutionally required to be served by a High Court so that each citizen had a High Court above him to protect his rights.

To understand our unique history, consider that India was ten British Indian provinces and hundreds of big and small independent Indian principalities. In addition to this there were hundreds of zamindars, jagirdars, estates. At its zenith, British India included present India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma. The princes had their own treaties with the East India Company and later with the British sovereign. The British were the paramount power over 565 princely states till their paramountcy lapsed in 1947. Out of these, 118 were salute states and 200 really small states, the size of a couple of villages or a small town. The princes, for administrative convenience of the paramount power, were grouped into Rajputana, Saurashtra, Hyderabad, Mysore, Kashmir and so on. Nevertheless, the judiciary in the princely states was vastly different from that in the British-Indian provinces, none of them came under any Indian High Court.

When the Constitution came into force, the provinces morphed into Part A states. Groupings of princely states became Part B states. Union Territories became Part C and Andamans, Part D. Different states grew in judicial stature in different ways. The older Indian High Courts had developed strong traditions and practices which took time to develop in the newer courts. The functioning of High Courts was also affected by frequent changes in their territorial jurisdictions. Some High Courts continued as they were before the Constitution, but some were newly formed and underwent drastic changes in their territorial boundaries, Punjab & Haryana High Court being one of them.

The transfer of a High Court judge may be constitutionally permissible, but may not be necessary any more. State judiciaries have settled down on a permanent basis. The transfer policy needs revision, and all transferred judges should be transferred back to their parent High Courts. The Constitution has given the power to the president to transfer High Court judges. The question is not the existence of power, but the frequent exercise of the power to transfer. Ending transfer of judges shall make High Courts once again judicially strong, more effective and independent.

Many aspects of justice delivery are necessarily very local. Each region has its own history, each has been through different stages of development, each has its own legislative track record and judicial precedents. Trial court records are in the local language. As regards areas which were part of the princely states, each followed its own path to accession to the Union of India. There was a provision for them to accede to the Indian Federation under the 1935 Act, but no princely state accepted this provision, fearing loss of autonomy.

Constitutionally, India is a Union of States but before the Union came into existence, each geographic area, province or princely state had its own system of administration of justice based on its own laws and customs. This was and should be the real essence of federalism.

Read Also: Kerala High Court extends stay on trial in Sessions court against Malayalam actor

There is a different way to look at transfers. Under the Constitution, each state has its own executive, legislature and judiciary. The governor, the chief minister and his council of ministers, the Speaker and the legislators, and the chief justice and his companion judges, all perform sovereign functions. No head of the state executive or legislature can be transferred. This must also be the rule for the state judiciary. In no other country are judges transferred from the court after appointment. One can never conceive of a judge from New York being sent to Texas or a judge from Scotland to Wales.

When a judge is transferred, the transferee court gets a lonely judge who is well into middle age and misses his family. It is difficult for him to look after aged parents or settle his children or arrange their marriages. The judge is forever planning visits home and unable to concentrate enough on court work.

Transfer of chief justices of High Courts away from their parent High Courts is based on the rule that a judge cannot be appointed chief justice of his parent High Court. This means that the court where he has spent his entire life, first at the Bar and then on the Bench, may not be the best court for him to head. He must be sent to a new court where he will be expected to pick up able, experienced, respectable advocate candidates for elevation to fill judicial vacancies. The urgency of quick judicial appointments is real; Indian High Courts require 404 more judges, as of October 2020, when only 675 judges are in position. For a new chief justice, unfamiliar with the local Bar, this can be a bit tricky. So often, the collegium’s view does not prevail and the list is returned. The collegium system requires the chief justice to have two senior judges with him in the collegium, who may or may not be co-operative. This leaves citizens at the mercy of a slow system, with mounting arrears. The transfer policy for chief justices and judges needs to be revisited.

Also Read: 15-yr-old dies in custody in Birbhum dist, Calcutta High Court asks for report

—The writer is former judge, Punjab & Haryana High Court, Chandigarh and former judge, United Nations Appeals Tribunal, New York