By Abhinav Mehrotra

Hate speeches have seen an exponential rise in recent times. While the issue has been dealt with in the past through case laws and various provisions under the Indian Penal Code, 1860, and Article 19 (2) of the Constitution, there is a need for a more direct declaration. There have been reasonable restrictions under the purview of these laws such as “incitement to an offence”, “defamation” or “security of the state”, but obviously much more needs to be done.

This sentiment assumes significance in the light of recent controversial religious events held in Delhi and Haridwar where speakers allegedly made hate speeches and called for violence against Muslims and Christians and waging a war scarier than the 1857 revolt. Similarly, the imprisonment of the developers of apps like Bulli Bai and Sulli Deals that created profiles of Muslim women and described them as “deals of the day” have highlighted the venom again the Muslim community.

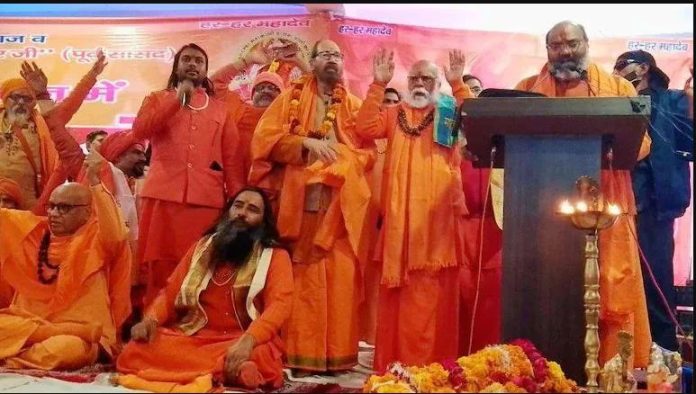

The dangerous effects of the hate speeches at the Dharma Sansad or religious assembly in Uttarakhand led to a petition being filed in the Supreme Court by a former judge of Patna High Court, Justice Anjana Prakash, and journalist Qurban Ali. Notices were sent out to the state government, central government and Delhi Police.

The petition said that between December 17 and 19 at two separate events in Delhi held by the Hindu Yuva Vahini and in Haridwar by religious leader Yati Narsinghanand, open calls were given for the genocide of Muslims and use of weapons against them. To make matters worse, they were seen in a video laughing with a police officer, who they said will be “on our side”.

Another shocking incident was the development of apps which used photos of Muslim women and putting them up for “auction”. This led to a huge furore and nearly 4,500 people signing an open letter to Chief Justice of India NV Ramana, asking him to register a suo motu petition on the targeting of Muslim women through apps like “Sulli Deals” and “Bulli Bai”.

The letter reads: “While the very action of downloading and posting pictures and private details of Muslim women, in both instances, was not only non-consensual and in violation of the right to privacy, it was clearly meant to degrade, dehumanize, vilify and demean Muslim women. ‘Auctioning’ women in this manner is a depraved attempt to commodify them and strip them of any personhood or dignity. This is a blatant violation of the very fundamental right to live with dignity and the right to bodily autonomy protected under Article 21 of our Constitution.”

It stressed that the “public auction of Muslim women is an extreme form of vilification of Muslims reducing them to non-citizens and sub-humans. This only points to the utter moral bankruptcy in our society where communal elements openly target, bully and perpetuate sexual violence against women with alarming impunity. Read along with the public calls for genocide on the streets of Delhi earlier last year, and at the Dharam Sansad in Haridwar more recently, it is evident that instances such as these are carefully strategized hate crimes pushing our country into a dark abyss to which there can be no turning a blind eye to anymore”.

In this context, it is important to understand why India as a country, known for its secularist values, is now facing these attacks on its constitutional principles and what are the social and legal implications of such incidents.

The right to free speech and expression is a constitutional right under Article 19(1)(a) and is necessary to ensure free exchange of ideas in the absence of government regulation, specifically when it comes to diverse opinions and dissent. While an individual has the right to participate in democratic decisions that affect him, the line drawn through reasonable restrictions needs to be respected to maintain the security and integrity of those sections of people that are numerically lower in number.

So, there is a need to specifically understand what constitutes hate speech and hate crimes and what could be expected going forward in terms of the safeguarding of rights of groups and individuals who have been targets of such hideous campaigns.

In simple terms, hate speech is based on historical stereotypes or symbolism targeting minority communities based on characteristics of caste, religion, gender, etc. In a similar vein, from a sociological perspective, hate crimes can be understood as targeting victims based on their membership of a social group based on race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, class, ethnicity, nationality, age, sex or gender identity.

Further, a UNESCO report published in 2015 defined it as speech at “the intersection of multiple tensions and as the expression of conflicts between different groups within and across societies”. Similarly, the TK Viswanathan Committee that also investigated the issue defined it as “hate speech must be viewed through the lens of the right to equality and relates to speech not merely offensive or hurtful to specific individuals, but also inciting discrimination or violence on the basis of inclusion of individuals within certain groups”.

Coming to the legal side on these issues, the Indian Penal Code, 1860 under Sections 153A, 153B, 295A, 298, 505(1) and 505(2) aims to curb hate speech based on religion, ethnicity, culture or race. Under these sections, any form of speech that “promotes disharmony, enmity, hatred or ill-will” or “offends” or “insults” is liable to be punished. Even under the 267th Report of the Law Commission of India, it is based on similar criteria, i.e. an incitement to hatred primarily against a group of persons defined in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religious belief through any word written or spoken, signs, visible representations within the hearing or sight of a person with the intention to cause fear or alarm, or incitement to violence.

There are a plethora of cases that have dealt with these issues by the Supreme Court. To illustrate, in State of Karnataka vs Praveen Bhai Thogadia, the Supreme Court emphasised the need to sustain communal harmony to ensure the welfare of the people, whereas in the case of Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan, it underlined the impact hate speech can have on the targeted groups’ ability to respond and how it can be a stimulus for further attacks.

From a comparative aspect, in countries like the US and the UK where a “clear and present danger” with imminent and direct cause must be established, Indian law provides a wider ambit. For example, in the US, free speech is “protected as an absolute and fundamental right under the Fifth Amendment”. This protection extends to an expression like that of “xenophobia, racism and religious discrimination” until and unless it furthers “direct violence against an individual and/or a group”.

In contrast, European nations place more emphasis on “civility and respect” such as in Germany’s Basic Law of 1949 which says that “protection against insult” is a right and is also guaranteed in its First Article.

Coming to India, the core of the issue is that nationalism is now being built by arousing religious sentiments and instigating animosity against followers of other beliefs. Historically, the idea of nationalism was centred around the Independence movement where it was used as an ideology to unite against the foreign occupation. But at present, it is affecting the safety of our own citizens.

What needs to be understood is that it is from the formative stages in life of a child that the attributes of respecting the dignity of all communities must be incorporated through the educational system. Though present to some extent in our course curriculum, it is not in a comprehensive and detailed manner.

History talks about national unity for which leaders fought and struggled. However, there were also elements of alien enemies, beginning with Muslim rulers which unconsciously led to the belief that there has always been a Hindu nation constantly fighting against certain evil powers.

In this regard, inspiration must be drawn from the statement of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel before the Constituent Assembly on May 25, 1949. As he was presenting the report of the Advisory Committee on Minorities, he said: “If they really have come honestly to the conclusion that in the changed conditions of this country, it is in the interest of all to lay down real and genuine foundations of a secular state, then nothing is better for the minorities than to trust the good sense and sense of fairness of the majority, and to place confidence in them. So also it is for us who happen to be in a majority to think about what the minorities feel…But in the long run, it would be in the interest of all to forget that there is anything like majority or minority in this country and that in India there is only one community.”

—The writer is a Lecturer at OP Jindal Global University and holds an LL.M in International Human Rights Law from the University of Leeds