The CBI is gearing up to probe another past boss. A look into the maze within the labyrinth

~By Sujit Bhar

The case of former Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) director Amar Pratap Singh is a quizzical one. The agency has filed an FIR against its own director, a first, but questions arise as to the timing of the “sudden revival of interest” and as to who let the cat on the mouse, and why?

The CBI hasn’t just stumbled onto Singh’s case. By Singh’s own admission, his BBM messages “are mostly personal and innocuous in nature as between friends. Majority are after I retired from CBI in 2012 November,” he has been quoted as saying. The messages were available even on social media sites for a long time.

The allegations against Singh are serious. Initially it was a case of him securing illegal favours for businessmen in collusion with meat exporter and prominent hawala operator Moin Qureshi. By top-level corruption standards of India, this is chicken feed.

Now the CBI is looking into whether Singh’s actions were impacting the very functioning of the agency.

During his tenure, Singh’s agency was involved in investigating the huge Andhra Pradesh Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (APIIC)-Emaar township project scandal, in which BP Acharya (IAS), former Chairman and Managing Director of APIIC, allegedly entered into a conspiracy with officials of Emaar Group and some public servants to cheat APIIC and secure wrongful gains for Emaar.

Not only was APIIC’s equity in the project diluted, Emaar was allowed to bring in its group company Emaar MGF Land Ltd as co-developer for the 258-acre integrated township project (at Gachchibowli, a prime area of Hyderabad). Then, when plots were sold, they were heavily under-invoiced, resulting in huge gain for the developers and their agents and loss for the government. The CBI first arrested Acharya and later Koneru Prasad, one involved in the sales.

Now the CBI has filed an FIR against Singh on a complaint from the Enforcement Directorate, agency spokesperson RK Gaur has been reported as saying.

The allegation is that the agency had gone soft on the accused and Singh and Qureshi were involved in it. No figures on the money involved have been mentioned, but it is said to be astronomical.

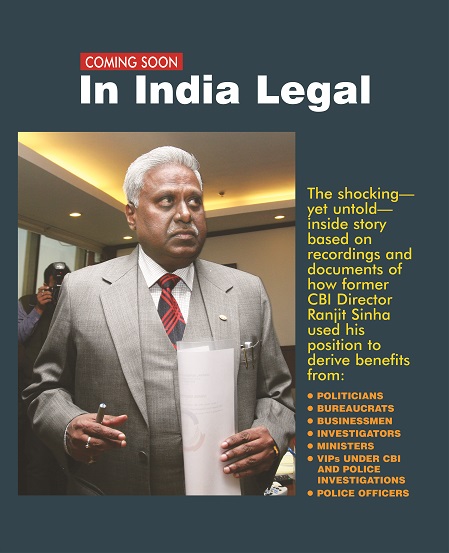

As it stands, two things come out. Firstly, how is it that the CBI has, again, been given the responsibility of investigating another of its own directors? Earlier Ranjit Sinha, former director, was put under the CBI scanner in the coal scam.

As a senior former Intelligence Branch (IB) official disclosed to this correspondent on the condition of anonymity: “I have no issues with any agency investigating a former employee/boss; unless any personal loyalty exists between the investigating officer and the accused, it will go as per norms. My contention is about the timing of the prod from ED. This has been in the air for a while and it was just a case of a former director getting favours done through government agencies with a hawala trader as a front. Now the scope has been widened.”

So what does the former IB official suspect? Which, is the second part. “I suspect this to be, firstly, a case of political bickering on the spoils of a scam. The spoils add up to hundreds of crores (it was estimated at Rs 136 crore, but other estimates point upwards), there has to be some sharing, without which the corrupt system is bound to hit back. Remember, the state of Telangana was carved out only in June 2014. Dig a little and you will come up with more political wheeler-dealers,” he said.

“Secondly, also, remember that 2G and coal allocation cases were registered during Singh’s tenure,” said the former official. The indication was clear. The other CBI director under investigation, Ranjit Sinha, Singh’s successor, was being probed for the 2G and coal scams.

Singh headed the agency between November 30, 2010 and November 30, 2012. Qureshi had become close to him through Singh’s wife, who was a friend of Qureshi’s wife. Singh (who was not yet the CBI chief) and Qureshi developed an extraordinary “working relationship”. When Singh became head of the agency, this relationship blossomed.

With his term coming to an end, Singh needed to protect his “investments”. Singh and Sinha were close and it was only natural that Singh recommend Sinha’s name to the ministry to be his successor. That was done and hence Sinha also benefited in getting to know Qureshi and according to the visitors’ diary (log) kept at the CBI director’s residence, Qureshi was a frequent visitor of Sinha.

The relationship between Sinha and Singh was always good, and if it did sour, it certainly sprung from an unspoken mandate of faith that was breached. This could lead from several internal as well as external factors.

The dependence of the agency (CBI) on its political bosses has always clouded its decision-making process. There is a possibility now that even internal equations maybe have been altered because of this. No clear internal system exists within the agency to separate internal lobbying from the operational side. This is what the senior ex-IB official was referring to.

Sandhi Mukherjee, a former senior IPS officer, who has campaigned for the true independence of investigative and law enforcement agencies, believes that the case of the Supreme Court directing an agency to investigate its own boss is technically a correct one, though it was not up to the Supreme Court to decide or know the internal politics and loyalties in the agency. “There is too much political interference. No agency would be in a position to deliver an impartial investigation. There has to be a different level of oversight. The public needs to be told that justice is available at all times.”

Mukherjee indicated that each boss of an agency creates his own team of loyalists, who remain loyal even after the boss has been removed. So was this the result of a clash of two sets of loyalists? Or was it a loss of faith between two headstrong leaders?

An interesting case just got even more interesting.