The traditional friendship between India and Russia has developed wrinkles, thanks to Moscow’s growing closeness to Pakistan and China

~By Seema Guha

As strategic dynamics in the world change, so is India’s traditional friendship with Russia, a country which has stood by it all through the Cold War years and up until recently. Russian President Vladimir Putin was singled out by the US and its allies as an enemy of the West ever since the annexation of Crimea in 2014. The continuing problems in Ukraine and Russia’s support for Bashar al-Assad of Syria have all added to the new Cold War between the US and Russia.

This could, of course, change when US president-elect Donald Trump takes over. But in recent years, President Putin has moved closer to China to counter both western sanctions and the need to create some strategic space following the expansion of NATO to Russia’s backyard.

This has had repercussions on India’s strategic ties with Russia, though both sides still maintain that they remain fast friends. India continues to buy defence equipment from Russia and during Putin’s visit in October, both countries signed fresh defence deals of around $5 billion.

Moscow had always stood by India during any dust-up with Pakistan. In fact, at one time, the Russians refused to sell defence equipment to Pakistan. During the Bangladesh Liberation war, Russia was the only major country that stood by India, with the Treaty of Friendship signed in 1971 before the Bangladesh war. When the US was sending its Seventh Fleet towards the Bay of Bengal to help Pakistan, Russia stood like a rock behind India.

INDIA’S DISAPPOINTMENT

But now this equation is changing. Some of the current coolness has to do with Russia’s changing priorities and its recent engagement with Pakistan. Last September, even as India was trying its utmost to isolate Pakistan following the Uri attack where 18 Indian soldiers were killed, Russia went ahead with its planned exercises with Pakistani troopers. It was the first-ever military exercise between the two countries.

New Delhi is naturally disappointed. The sore point was that it came at a time when India was working towards isolating Pakistan. That itself was a foolish notion considering that neither the US nor western democracies and certainly not China would agree to it.

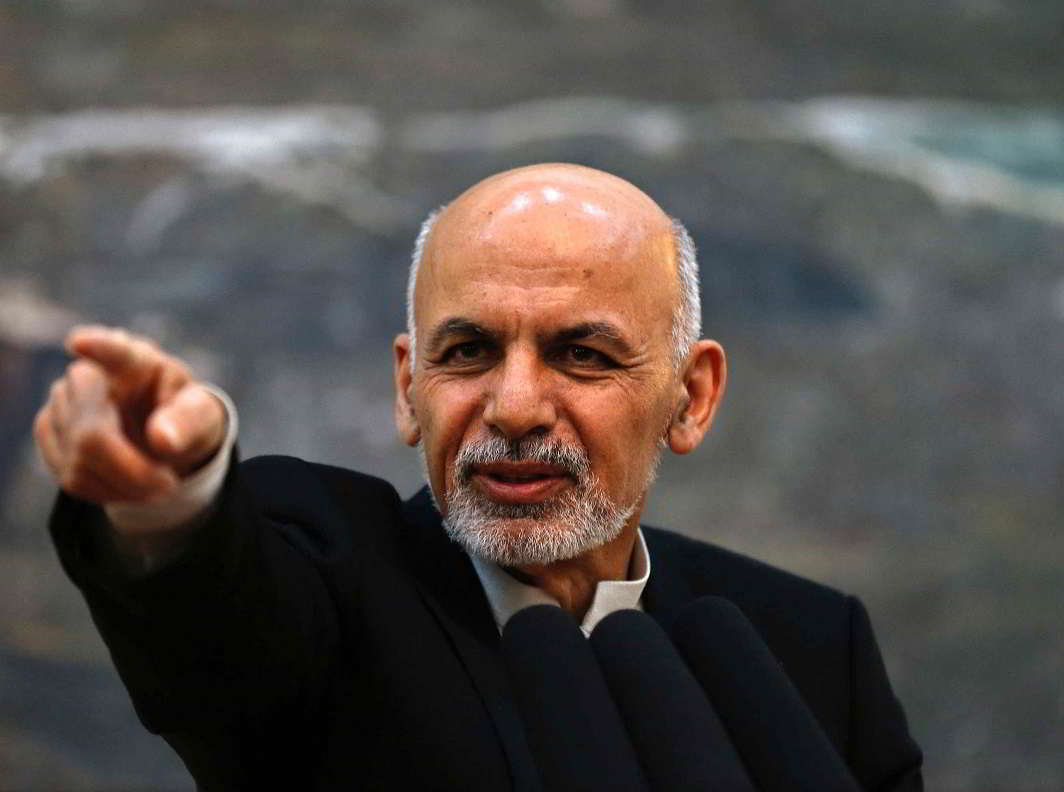

Added to this is Russia’s change of tact on Afghanistan. India, Russia and Iran had worked together to bolster the Northern Alliance against the Taliban when it was ruling Kabul. Delhi and Moscow had always agreed that there should not be any distinction between groups of terrorists. Terrorists were to be condemned, and there could never be a distinction between my terrorist and yours. While India is also of the view that the Taliban should be part of any future political settlement for lasting stability in Afghanistan, there is a red line. Those who want peace must adhere to Afghanistan’s constitution. That is also the view of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, as well as the former president, Hamid Karzai.

Russia has its own reasons to engage with Pakistan and the Taliban. Its worry about fleeing IS fighters making their way from Syria-Iraq to Afghanistan has forced it to regard the Taliban as the lesser evil.

But now suddenly, these distinctions are being blurred by Russia in its effort to reach out to the Taliban. Moscow is toeing Pakistan and China’s line on the Taliban and all three are working together to get the UNSC to remove sanctions against some individuals and entities once targeted by the global body. These include members of the Haqqani network, who work closely with the Taliban. The Haqqani group is virulently anti-India and is used by Pakistan’s spy agency, the ISI, to target Indian interests in Afghanistan. Delhi and Kabul blame the ISI and the Haqqani network for the suicide attack on the Indian embassy in 2008, where an Indian diplomat and a senior defence attaché were killed. In 2009, the Indian embassy was again targeted. New Delhi finds it hard to digest Moscow’s about-turn where it is batting for the Taliban which now includes the Haqqani clan and is trying to get the UN to lift restrictions on them.

But Russia has its own reasons to engage with Pakistan and the Taliban. Russia’s worry about fleeing IS fighters making their way from Syria-Iraq and Europe to Afghanistan has forced it to regard the Taliban as the lesser evil. According to some estimates, there are around 3,000 IS fighters in Afghanistan. As Ghani’s forces are losing more and more ground to the Taliban in Afghanistan, Moscow is opening a line to them. In this, Pakistan remains a useful conduit, having already helped China to engage with the Taliban.

Russia believes that the Taliban will be in a better position to fight the IS rather than the Afghan National Army. And like Pakistan and China, it believes that it is much better to have the Taliban in Afghanistan than the IS. Russia also fears that the IS will spread to its Muslim-dominated Chechen province and it wants to ensure that this population is not infiltrated. The Russians know the strength of IS fighters, having combated them in Syria.

DEFENCE MARKET

Russia is in talks for an agreement to sell SU-35 fighters to Pakistan. This would have been unthinkable in the past, but Russia is hoping to expand its defence production market, which is mainly dependent on India and China. Though the deal has not yet come through, it is likely to be sealed in a couple of months. Moscow had earlier turned down requests for arms from Pakistan, going with Delhi’s argument that these arms would end up being used against it. That argument possibly does not hold much value now.

There have also been reports in the Pakistan press about Moscow wanting to be part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). India is opposed to the CPEC mainly because some of the corridor passes through Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir which India claims as its territory. Though Russia and Pakistan have joint projects, including a gas pipeline one, so far the former has shown no inclination to join the $46-billion CPEC. But Russia is always in search of warm water ports, and if Pakistan offers either Gwadar or an alternative port for Russian vessels in future, one can expect Moscow to grab the opportunity.

Yet all is not lost. Co-operation in defence, space, hydrocarbons and nuclear energy remains on track. Indo-Russian ties have always been more at a government level than between individual companies. Despite much effort, co-operation in their private sectors has not looked up.

OVER-EMOTIONAL INDIANS

Nandan Unnikrishnan of Observer Research Foundation said: “There are wrinkles in the ties between the two traditional friends. These need to be smoothed out before they become insurmountable.’’ Indians, he explained, become over-emotional about Russia. Considering that Pakistan and China are regarded as India’s adversaries, Russia getting close to them is like a stab in the back for many Indians.

Delhi must also realize that Moscow possibly feels the same about India’s warming ties with the US—with military exercises, across-the-board co-operation and buying of defence equipment. Seen from Moscow’s prism, India is cosying up to the US in the same way.

Unnikrishnan said it was time for Indian policy makers to decide how to perceive the future. “If they believe in a bi-polar world where the US and China are the big players, it is but natural that Delhi will veer towards Washington. But if policy makers see a multi-polar world, Russia has to remain a friend. We need to have a clear approach.’’

He said that despite Russia no longer being a superpower, under Putin, it had shown that it was a major player. Whether it is Syria, Ukraine or the Middle East peace process, Moscow matters. “It is up to India now to decide on its world view and act accordingly,’’ Unnikrishnan said. If Russia is a declining power, so be it. There should be no heartburn. He said Delhi and Moscow should sit across the table and talk.

An emotional response from India is both foolish and unwarranted.

Lead picture: Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Vladimir Putin during the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, in June 2016. Photo: UNI