In a surprising U-turn, Modi government decides to hold talks with Pakistan on the Indus Water Commission

~By Seema Guha

In a break from its position since the Uri attack, not to talk to Pakistan till terror strikes were stopped, the Narendra Modi government has decided to attend a meeting of the Indus Water Commission in Lahore later this month. The dates are likely to be March 20 and 21. Foreign ministry officials will also attend the meeting. The move is welcome, considering it involves the sanctity of an international agreement which has so far been able to serve the interests of both countries.

The Indus Water Treaty is regarded as one of the most successful international agreements, which has stood the test of three wars, numerous terror strikes and the ups and downs of the volatile ties between the two South Asian neighbours.

BONE OF CONTENTION

The Treaty is under threat, with Pakistan accusing India of breaking the provisions of the Treaty by building the Kishanganga hydroelectric project in North Kashmir and the Ratle project in Jammu. New Delhi maintains that run-of-the river projects are allowed by international law. According to the Treaty, technical objections by either party are referred to neutral experts if the countries cannot resolve it bilaterally. Only disputes that require interpretation of the Treaty are handled by a Court of Arbitration.

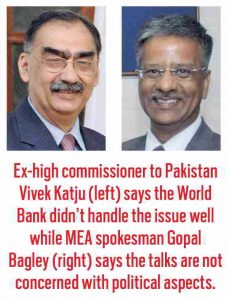

“The current problem regarding the Kishanganga and Ratle hydel projects has much to do with the World Bank’s mishandling of the issue,’’ former Indian high commissioner to Pakistan Vivek Katju told India Legal. “Neutrality cannot imply refusal to make a determination,’’ he added. Katju believes that the Indian request for a neutral expert to go into these differences is correct and the Pakistani demand for a Court of Arbitration not sustainable.

The World Bank maintains that “the two countries disagree over whether the technical design features of the two hydroelectric plants contravene the Treaty. The plants are on respectively a tributary each of the Jhelum and the Chenab rivers. The Treaty designates these two rivers as well as the Indus as the ‘western rivers’ to which Pakistan has unrestricted use. Among other uses, India is permitted to construct hydroelectric power facilities on these rivers subject to constraints specified in Annexures to the Treaty.’’

The World Bank maintains that “the two countries disagree over whether the technical design features of the two hydroelectric plants contravene the Treaty. The plants are on respectively a tributary each of the Jhelum and the Chenab rivers. The Treaty designates these two rivers as well as the Indus as the ‘western rivers’ to which Pakistan has unrestricted use. Among other uses, India is permitted to construct hydroelectric power facilities on these rivers subject to constraints specified in Annexures to the Treaty.’’

India wants a neutral observer to look into Pakistan’s complaints, while Pakistan wants to take up the matter for arbitration. Pakistan took up the case of the Kishanganga project for arbitration in 2010. The ruling was given in 2013. The project was allowed with certain modifications. India had to ensure that a minimum of nine cusecs of water is discharged into the river. Pakistan complained about the dam to be built for the Ratle project and is now fighting over both issues.

Islamabad accuses New Delhi of not fulfilling its Treaty obligations. A leading Pakistani English daily quoted a close aide of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif as saying: “Pakistan will not accept any modifications or changes to the provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty. Our position is based on the principles enshrined in the Treaty. And the Treaty must be honoured in letter and spirit.”

POLITICAL ROW

The deteriorating political ties between the two arch rivals have added to the problems. Ever since the Uri attack and the unrest in Kashmir (which Delhi believes is fuelled by Pakistan), sharing of the Indus waters has become a major issue. Prime Minister Modi had said that “blood and water cannot flow together’’. India was threatening to pull out of the Treaty and send Pakistan the message that unless terror was stopped, all cooperation, including water sharing, will stop. Prime Minister Modi, himself, sat through high-level meetings reviewing the Treaty and considering his options. Many hardliners in India believe that the Treaty should be abrogated. They blame India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru of having been over-generous and giving Pakistan more than its share of the Indus waters. For a while it seemed as if the government would actually pull out. But there has now been a rethink.

With the Partition of India, the waters of the five Punjab rivers had to be divided between the two countries. It was not an easy task negotiating the deal and took nine years to complete. It was brokered by the World Bank and the final agreement was signed in 1960 by then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and president Ayub Khan. The World Bank is also a signatory to the Treaty. At the time the deal was signed it was hailed by the international community as a major achievement. Former US President Dwight Eisenhower described it as “one bright spot … in a very depressing world picture that we see so often”.

The Indus Water Treaty gives India control over the three eastern rivers of the Indus basin— the Beas, the Ravi and the Sutlej—while Pakistan has the three western rivers— the Indus, the Chenab and the Jhelum

DETAILS OF THE TREATY

The Treaty gives India control over the three eastern rivers of the Indus basin— the Beas, the Ravi and the Sutlej—while Pakistan has the three western rivers— the Indus, the Chenab and the Jhelum. A mechanism was set up to oversee the working of the Treaty. This was the Permanent Indus Commission, which includes a commissioner from each country. The commissioners meet at least once a year in alternate capitals to smoothen out the workings of the Treaty. Since the signing of the Treaty, officials of India and Pakistan have met 112 times.

Having decided to punish Pakistan by boycotting last year’s SAARC summit in Islamabad and trying its best to diplomatically isolate that country, the about-turn on the Indus Treaty is surprising. The External Affairs Ministry is playing down the planned visit of officials to Lahore, saying a meeting had to be held between both sides once a year.

Perhaps with the UP elections out of the way, the government has decided to gradually re-engage with Pakistan. The MEA remains defensive and is taking care to point out that this meeting does not in any way suggest the resumption of bilateral dialogue.

“This does not amount to talks between the two governments. The talks are not concerned with political aspects but only with the technicalities of the commission,” Gopal Bagley, the new spokesman of the External Affairs Ministry says. Bagley was earlier the number two in the Indian High Commission in Islamabad. His last job was as Joint Secretary incharge of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran.

The India-Pakistan meeting in Lahore may help both sides review their respective positions. But the Indus Water Treaty is under dire threat as water is likely to be used as a diplomatic tool in future. Unlike other prime ministers, including the BJP’s Atal Behari Vajpayee, Narendra Modi will have no qualms about turning off Pakistan’s water supply, if necessary. Vajpayee was provoked during the Kargil war and after the parliament attack of 2001. With Modi this can be a legitimate weapon of retaliation.