In tune with a Supreme Court judgment, the prosecution wing has been separated from the J&K Police and made an independent entity so that it can work objectively

By Pushp Saraf

In a major shake-up, the prosecution wing has been separated from the Jammu and Kashmir Police and made an independent entity by creating a J&K Prosecution Service. This has been done to achieve a “national norm” in conformity with the Criminal Procedure Code and recommendations of the Law Commission. Above all, it is in tune with the Supreme Court judgment of April 21, 1995 in the S.B. Shahane and Ors vs State Of Maharashtra And Anr case.

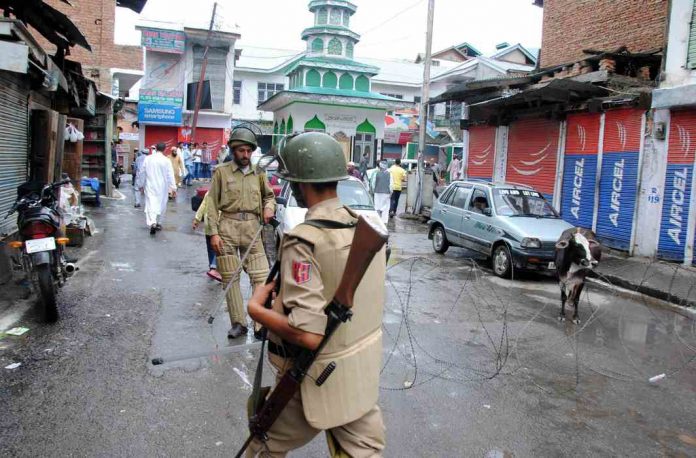

The move cuts into the size and influence of the most-talked-about force in recent years of militancy. It became unavoidable with J&K losing its special status guaranteed under Article 370. The Article had enabled it to maintain certain distinct features especially with respect to the functioning of the police. J&K has also been downgraded to a Union Territory (UT). Deprived of its status as a state, it no longer controls the police as the Union government has directly assumed responsibility for law and order.

The concepts motivating the separation of the prosecution arm are impartiality and objectivity. A report of the Law Commission explains: “Prosecutors have duties to the State, to the public, to the Court and to the accused and, therefore, they have to be fair and objective while discharging their duties.”

The report elaborates: “Public Prosecutor is defined in some countries as a public authority who, on behalf of society and in the public interest, ensures the application of the law where the breach of the law carries a criminal sanction and who takes into account both the rights of the individual and the necessary effectiveness of the criminal justice system.”

Public prosecutors should not worry about any pressure or influence being exerted on them. They are considered vulnerable if they are part of the police department as they may find it difficult to resist the temptation of justifying their own role as investigators to secure a higher conviction rate for the sake of promotions. The Union government, regardless of the party in power, has applied its mind to the issue from time to time.

In 2000, a committee headed by Justice VS Malimath had suggested the creation of a new post of director of prosecution in every state “to facilitate effective coordination between the investigating and prosecuting officers under the guidance of the Advocate General”. The Law Commission has been called upon to offer its advice more than once. Apart from its 14th report submitted in 1958, which is part of the apex court’s 1995 judgment, the Commission also discussed the matter in its 197th report (2006) for primarily ensuring that states followed the same pattern in selecting prosecutors.

In 2000, a committee headed by Justice VS Malimath had suggested the creation of a new post of director of prosecution in every state “to facilitate effective coordination between the investigating and prosecuting officers under the guidance of the Advocate General”. The Law Commission has been called upon to offer its advice more than once. Apart from its 14th report submitted in 1958, which is part of the apex court’s 1995 judgment, the Commission also discussed the matter in its 197th report (2006) for primarily ensuring that states followed the same pattern in selecting prosecutors.

Following the model elsewhere, J&K has set up a directorate of prosecution with an Inspector-General of Police, Syed Ahfadul Mujtaba, becoming its first director-general. Several other appointments have also been made. It is like old wine in a new bottle with many officers who were part of the police prosecution division being considered useful for the new organisation because of their “valuable” experience. Officers have been burdened with additional charges before one for each of 20 districts is found. Rules have yet to be framed. Syed Mujtaba had expressed hope in a newspaper interview: “The pendency, which is at over 99,000 cases for 2018 and close to that number for 2019 as well, should go down with the new wing coming into place.”

His appointment was announced on November 14. On December 9, the UT administration sanctioned 12 offices of deputy directors (prosecution) and through a separate order appointed seven police officers (DDPs) to look after 20 districts: Maroof Ahmed Manhas in Srinagar district with additional charge of Ganderbal and Bandipora; Riyaz Ahmed Darzi in charge of Anantnag, Kulgam and Shopian with additional charge of Budgam and Pulwama; Murtaza Nasir in Baramulla with additional charge of Kupwara; Parshotam Lal in Jammu with additional charge of Rajouri and Poonch; Pawan Kumar Khajoria in charge of Kathua and Samba; Mahesh Kumar in charge of Udhampur and Reasi; and Ravinder Kumar Rao in charge of Doda and Kishtwar with additional charge of Ramban.

Besides, Aejaz Ahmad Bhat was made Chief Prosecuting Officer (CPO) in the office of Director General of Prosecution, Mohammad Shafi, CPO in the Armed Police Headquarters, Ghulam Jeelani Dar, CPO, Anti Corruption Bureau and Ashish Rathore, who is awaiting orders of posting to continue as CPO, Sher-i-Kashmir Police Academy, Udhampur till Rajesh Gill takes over.

It has been a step-by-step approach. The State Administrative Council (SAC) headed by former Governor Satya Pal Malik had taken the decision to launch the prosecution service and the Directorate of Prosecution on October 22 in light of the J&K State Reorganisation Act passed by Parliament in August.

The SAC took the cue from the judgment of a division bench of the Supreme Court, consisting of Justice Kuldip Singh and Justice N Venkatachala, in the S.B. Shahane and Ors vs State Of Maharashtra And Anr case.

The judgment appears to have laid down a criterion for the entire country even while being specific to one state. It directed the “Maharashtra Government to constitute a separate cadre of Assistant Public Prosecutors either on district-wise basis or on state-wise basis by creating a separate Prosecution Department for them and making the head to be appointed for such Department directly responsible to the State Government for their discipline and the conduct of all prosecutions by them before the Magistrates’ courts and further free such Prosecutors fully from the administrative and disciplinary control of the Police Department or its officers, if they still continue to be under such control”.

Justice Singh and Justice Venkatachala have discussed at length the purpose of Sections 24 and 25 of the CrPC as well as Parliament’s objective in enacting them, apart from the recommendations in the 14th report of the Law Commission prepared by legal luminaries like MC Setalvad. They observed: “When all the sub-sections of Section 25 of the Code are seen as a whole, it becomes clear therefrom, that there is a statutory obligation imposed on the State or the Central Governments, as the case may be, to appoint one or more Assistant Public Prosecutors in every district for conducting the prosecutions in the Magistrates’ courts concerned, and of making such Assistant Public Prosecutors independent of the Police Department or its officers entrusted with the duty of investigations of cases on which prosecutions are to be launched in courts, but constituting a separate cadre of such Assistant Public Prosecutors and creating a separate Prosecution Department for them, its head made directly responsible to the Government for such department’s work. The independence of Assistant Public Prosecutors sought to be achieved under the Scheme of the provisions in Section 25 of the Code is also sought to be achieved in respect of Public Prosecutors, becomes obvious from the scheme of the provisions in Section 24 of the Code.”

These provisions, according to the apex court, were “undisputedly inserted by the Parliament in the Code because of the fault found by the Law Commission in the conduct of prosecutions in Magistrates’ courts of the country by Police Prosecutors and remedial suggestions made by it in its 14th Report”.

Discussing the role of public prosecutors, the 14th report of the Law Commission said: “It is obvious that by the very fact of their being members of the Police Force and the nature of the duties they have to discharge in bringing a case in court, it is not possible for them to exhibit that degree of detachment which is necessary in a prosecutor. It is to be remembered that a belief prevails amongst the Police Officers that their promotion in the Department depends upon the number of convictions they are able to obtain as prosecuting officers… supervision of the work of these prosecuting officers is thus exercised by the Department Officials.”

The report had suggested the following remedial measures: “As a first step towards improvement, the prosecuting agency should be completely separated from the Police Department. In every district a separate prosecution department may be constituted and placed in charge of an official who may be called a ‘Director of Pubic Prosecutions’. The entire prosecution machinery in the District should be under his control. In order to ensure that he is not regarded as a part of the Police Department he should be an independent official directly responsible to the State Government. The departments of the machinery of the Criminal Justice, namely, the Investigation Department and the prosecuting department should thus be completely separated from each other.”

The judges endorsed these corrective steps. J&K as a UT has fallen in line with the rest of the country. Said a police officer: “The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Let us wait and watch whether the conviction rate goes up from less than 40 percent at the moment.”