In an attempt to tackle organised crime and gang wars, the state government has proposed a bill based on the draconian MCOCA, thereby creating a political storm

~By Vipin Pubby in Chandigarh

Various state governments have, from time to time, brought in or attempted to bring in draconian laws on the plea that organised crime cannot be dealt with ordinary laws. The latest to announce such an intention is the Congress government in Punjab, which is seeking special powers to contain increasing incidents of organised crime and gang wars.

The proposed legislation, which has created a political storm in the state, is to be based on the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA). The preamble to the MCOCA made its intentions clear: “The existing legal framework, ie the penal and procedural laws and the adjudicatory system, are found to be rather inadequate to curb or control the menace of organised crime. The government has, therefore, decided to enact a special law with stringent and deterrent provisions including in certain circumstances, power to intercept wire, electronic or oral communication to control the menace of organised crime.”

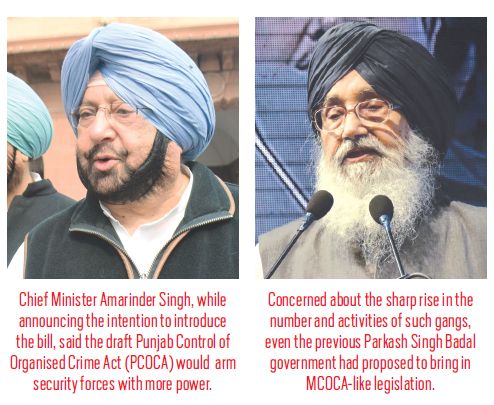

Chief Minister Amarinder Singh, while announcing his government’s intention to introduce the bill, said the draft Punjab Control of Organised Crime Act (PCOCA) would arm security forces with more power to tackle criminals, gangsters and radical forces.

The draft entails that “all confessions of criminals booked under the proposed Act can be made before the rank of superintendent of police and are admissible in a court of law. It also empowers a DIG-rank or above officer to invoke PCOCA with a note on why IPC is unable to handle the act of crime”.

The sweeping powers proposed to be given to the police have been prompted by a series of incidents involving organised crime and mushrooming of criminal gangs. Intelligence sources say there are 12 to 15 major criminal gangs, though the exact number of minor gangs affiliated to the major ones is not known. These gangs are involved in contract killings, blackmail, extortions and inter-gang rivalry.

Unlike the gangsters of UP, Bihar and other states, where unemployed or frustrated youth join such gangs, in Punjab it is to attain power and “show off”. Some of these gangsters belong to middle class families and include sons of police personnel and sportsmen.

The gangs began to flourish after the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD)-BJP government came to power in 2002. Certain gangs were also active in the state in the 1960s and ’70s, but little was heard about them during the nearly two-decade-long period of militancy.

It is believed that some of these gangsters had joined ranks with militants and took the cover of militancy to carry out nefarious activities. After the restoration of peace, these gangs again became active.

Significantly, many of these gang leaders made use of social media to prop themselves up. Posting pictures of well-armed gang leaders, at times uploaded by those in custody in jails, became a fad. Unlike the gangsters of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and other states, where unemployed or frustrated youth join such gangs, in Punjab it is to attain power and “show off”. Some of these gangsters belong to middle class families and include sons of police personnel and sportsmen.

Concerned about the sharp rise in the number and activities of such gangs, even the previous Parkash Singh Badal government had proposed to bring in MCOCA-like legislation to deal with this growing menace. State intelligence agencies at that time had estimated that there were 57 organised gangs, with some 400 members. The then deputy chief minister, Sukhbir Singh Badal, had proposed similar legislation but the state cabinet had not approved it after some of its members had expressed apprehensions over the political fallout of the move.

The cabinet note prepared for the purpose states that there are 57 active gangs in Punjab. It mentions that the conviction rate has been low for various reasons. Of the 115 cases filed against gangsters from 1996 till 2016, only 10 resulted in conviction because eyewitnesses in most cases turned hostile during trial, the note claims.

Although the Amarinder Singh government claimed that it had busted the gang that allegedly killed about half-a-dozen right-wing activists and leaders, including Brig Jagdish Gagneja, the proliferation of criminal gangs in the state is causing much concern.

The opposition SAD has so far not reacted to the proposal of the Amarinder Singh government but the Aam Aadmi Party has come out with a strong statement against it. The leader of the Opposition, Sukhpal Singh Khaira, in a statement warned the government not to enact the PCOCA, as “it is bound to be misused by the police and political hierarchy of the state to settle scores with their opponents”.

He said the proposed legislation would only “empower the police to intimidate people and indulge in corruption”, and added that his party would oppose tooth and nail any such “draconian law” in the Punjab Vidhan Sabha.

He said the proposed legislation would only “empower the police to intimidate people and indulge in corruption”, and added that his party would oppose tooth and nail any such “draconian law” in the Punjab Vidhan Sabha.

A similar piece of legislation, the Gujarat Control of Organised Crime Act (GUJCOCA), passed by the assembly in 2003, is still pending presidential assent. Some of its provisions are even more draconian than the Maharashtra Acts.

The Delhi government too extended MCOCA in January 2002 and has been making use of its provisions to nab gangsters.

Among other states, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have their own versions of MCOCA.

The Maharashtra Act is a precursor to the Prevention of Terrorism Activities (POTA) Act, 2002, passed by parliament with the objective of strengthening anti-terrorism powers in the wake of the attack on Parliament and other terrorist attacks during the tenure of the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government.

However, the Act was repealed two years later by the Manmohan Singh government in view of a large number of complaints against its abuse by law-enforcing authorities. About 4,000 people were detained during the two years that POTA was in force.

Prior to that, the infamous Terrorists and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) had come under heavy criticism due to misuse of its provisions. About 75,000 people were detained all over India under TADA. Almost 73,000 cases had to be subsequently withdrawn for lack of evidence.

TADA was enacted in 1985 by the then Congress government to deal with the Punjab militancy and other insurgency movements in the country.

It was amended in 1987 but again due to its massive abuse, was allowed to lapse in 1995.

Given the record of gross misuse of such Acts, the Punjab government may have to rethink its proposal or plug the loopholes to prevent the recurrence.