Above Illustration: Anthony Lawrence

As the NGT questions 10 states on improper appointment of chairpersons of State Pollution Control Boards, the centre seeks to weaken not just this tribunal but others as well

~By Venkatasubramanian

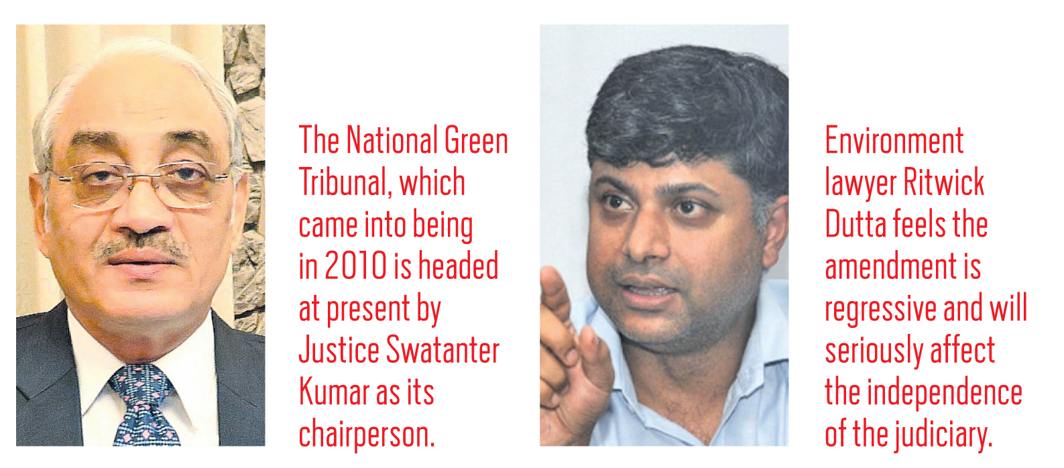

The National Green Tribunal, which came into being in 2010, has, according to litigants and lawyers appearing before it, emerged as the most effective environmental court in the world, capable of dealing with various challenges to the country’s environment. But it may not be in a position to keep that image any longer if the central government does not reverse an amendment it recently introduced through the Finance Act, 2017.

Section 182 of the Finance Act, inserted Section 10A of the NGT Act, 2010, enabling the Executive, rather than the parliament, to decide the qualification, appointment, terms of office, salaries and allowances, resignation and removal of its chairperson, judicial member and expert member. This is notwithstanding what other provisions of the NGT Act may say. Although it exempted the three members of the current NGT from this amendment, it made it clear that their successors would be governed by Section 184 of the Finance Act, 2017.

FINANCE ACT

Section 184, incidentally, applies to the chairperson and members of all tribunals, appellate tribunals and other authorities, not just the NGT. It enables the central government to make rules as mentioned above of the chairperson, vice-chairperson, chairman, vice-chairman, president, vice-president, presiding officer or member of the tribunal, appellate tribunal or, as the case may be, other authorities as specified.

Section 184 has three key provisos. The first says the appointees to the above posts shall hold office for such terms as specified by the central government, but not exceeding five years, and shall be eligible for reappointment. The second proviso imposed an age limit of 70 years for the chairperson or president, and in the case of others, 67 years. The third proviso protects their salary, allowances and other terms and conditions of service after appointment.

The Department of Revenue, Ministry of Finance, issued a notification on June 1, carrying the new rules to govern the tribunals, appellate tribunals, and other authorities.

CURBING NGT

While the notification affects the independence of all tribunals and quasi-judicial authorities, the specific amendment of the NGT Act has caused concern among environmental lawyers and activists. They have reposed great faith on it to protect India’s environment from the Executive, which may be amenable to extraneous influences from corporate bodies.

The NGT Act, 2010, mandates that the chairperson should be either a judge of the Supreme Court or has been one; is or has been a chief justice of a high court. The new rules, on the contrary, requires that the chairperson of NGT is or has been or is qualified to be a judge of the Supreme Court; is, or has been, a chief justice of a high court or has, for a period of not less than three years, held office as a judicial or expert member; or is a person of ability, integrity and standing and having special knowledge of and professional experience of not less than 25 years in law, including five years’ practical experience in the field of environment and forests.

Experts are concerned that this amendment will lead to NGT being headed by someone who has no legal background and training. If civil servants become chairpersons of NGT, they may not become impartial adjudicators because training and the ability to write reasoned judgments are key attributes of such objectivity.

WATERING DOWN

The new rules also dilute the qualifications of the judicial member of the NGT. To qualify as one, a person should be or has been judge of the Supreme Court or a judge of a high court or chief justice of a high court. The new rules provide that a judicial member is, or has been, or is qualified to be a judge of a high court; or has, for at least 10 years, held a judicial office in the territory of India.

Civil servants may not become impartial adjudicators because training and the ability to write reasoned judgments are key attributes of such objectivity.

Again, while the NGT Act required an expert member to be a doctorate with masters in science, the new rules require only a degree in science with five years experience in the field of environment. The NGT Act required expert members to be selected by a committee headed by a sitting judge of the Supreme Court to be appointed by the chief justice of India and comprising the chairperson of the NGT, in addition to experts in environment and forest policy.

The new rules have done away with the selection committee headed by a sitting judge of the Supreme Court. It will now be headed by a person to be nominated by the central government. The chairperson of the NGT is no longer the member of the selection committee and has been replaced by two secretaries of the government of India, which includes the secretary in the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF).

“In effect, there will be no judicial oversight in the selection of the expert members, as it exists at present. This whole amendment is regressive and seriously affects the independence of the judiciary,” said Ritwick Dutta, a well-known environment lawyer, in an article in Live Law, a legal news portal.

TERMS REDUCED

The reduction of the term of office of an NGT member from five to three years has also come under criticism as many qualified people will not consider joining the NGT because of the limited tenure. As it takes time to gain expertise on complex environmental issues, this will affect the quality of NGT’s decisions, it was stressed. Also if members complete their tenures before a case is disposed of, it would mean rehearing these cases afresh and lead to further delay. Short tenures would discourage talented, young, and otherwise eligible persons from joining the Tribunal, it was felt. A body which can attract only retired persons to join it is not likely to be a robust institution, with a pro-active interest in promoting environment, it was suggested.

In Union of India v R Gandhi, (2010) the Supreme Court inferred that the independence of the judiciary stood to suffer if the qualifications for appointment as members are diluted in haste. Increasing bureaucratic control over the selection of members of the Tribunal has ominous consequences, not only for the independent functioning of these bodies, but for the effective discharge of their duties as watchdogs.

As Dutta explains, NGT serves as the appellate body against decisions taken by secretaries of the government among others. It is very unlikely that the government will choose persons who are likely to overrule its decisions or take strict action with respect to the conduct of government officials, Dutta suggested. In R Gandhi, the Supreme Court indicted the practice of having secretaries of the government dominating selection committees of tribunals.

Worse, the NGT chairperson, who earlier had the status of a Supreme Court judge, will now be equated with that of the cabinet secretary if the new rule regarding his salary is implemented. It says that the chairperson shall be paid a salary of Rs 2,50,000 (fixed) and other allowances and benefits as are admissible to a central government officer holding posts carrying the same pay. The only officer who gets this salary under the central government is the cabinet secretary, Dutta pointed out. Judicial members of the NGT will also be equated with Group A civil servants of the central government in terms of their allowances, even though they perform judicial functions.

Other concerns too were expressed such as the enhanced control of the administrative ministry over the Tribunal in terms of the procedure for removal of the chairperson and other members and sanction of their leave applications.

STATE BOARDS

The central government’s attempt to tinker with the independence of tribunals comes in the wake of the NGT’s drive against incompetent persons holding the posts of chairpersons of State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs). On June 8, the NGT directed the chairpersons of 10 such boards to cease functioning, as their appointment did not comply with the Tribunal’s August 2016 judgment.

The states were Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Kerala, Rajasthan, Telengana, Haryana, Maharashtra, and Manipur. This was in pursuance of its earlier order in Rajendra Singh Bhandari v State of Uttarakhand and others, issued in August last year. The NGT laid down several guidelines in this case to ensure that the composition of SPCBs and the qualifications of persons appointed as chairpersons and member secretaries are in compliance with the letter and spirit of the law.

The provisions of the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1974 and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1981 require that the chairperson must have “special knowledge or practical experience in respect of matters relating to environmental protection”. The member secretaries are expected to possess qualification, knowledge and experience of scientific, engineering, or management aspects of pollution control, and must be engaged on a full-time basis.

In its August 2016 judgment, the NGT provided guidelines for how the terms “special knowledge” and “practical experience” in the context of the SPCB’s chairperson’s qualifications are to be understood, as they are not defined in the two laws. The NGT made it clear that any person with knowledge which is ordinary or casual in respect of environmental matters would not qualify or become eligible and only those with an academic qualification in the field of environmental protection from a recognised university would be eligible. Besides, the guidelines sought to ensure security of tenure of the members.

On July 10, the Supreme Court stayed further proceedings before the NGT in this case and decided to hear the appeals by states against the August 2016 judgment of the NGT within three weeks.

It is very likely that the Finance Act, 2017, which dilutes the independence of all tribunals, will be reviewed by the Supreme Court as it appears to be a knee-jerk reaction of the central government to NGT’s activist role in safeguarding the environment.