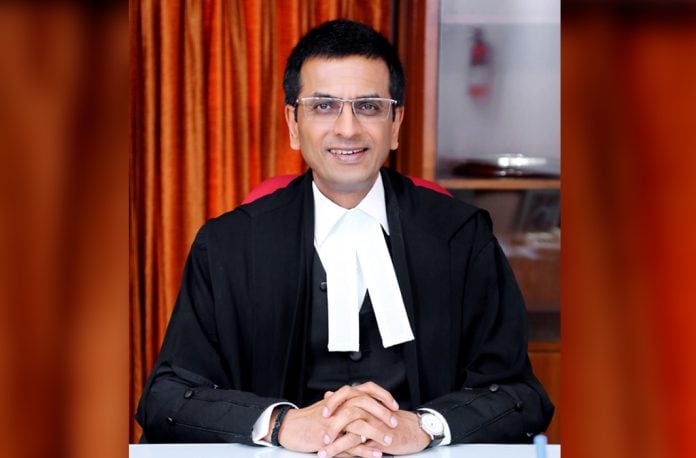

As the tenure of Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud comes to an end on November 10, the 50th CJI braces up to deliver some crucial verdicts in pressing issues such as the minority status of the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), validity of the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, and the wealth redistribution issue.

On February 1, after eight days of marathon arguments, a seven-judge Constitution Bench led by CJI Chandrachud had reserved its judgement on the minority status of AMU, which has been in the eye of the storm since 2006 when the Allahabad High Court struck down a 1981 amendment that declared it a minority institution.

In case the Apex Court declares AMU a minority institution, the SCs, STs and OBCs would not get reservation in admission. The verdict would set a judicial precedent for a similar legal battle over the status for the Jamia Millia Islamia University, which was declared a minority institution during the UPA government in 2011. The issue was referred to a seven-judge Constitution Bench on February 12, 2019.

On January 11, while noting that Article 30 of the Constitution was not intended to ‘ghettoise’ the minority, the Constitution Bench had pondered over whether the issue that AMU was a minority institution or not mattered, especially when it has continued to be an institute of national importance without the minority tag.

Another important issue that the CJI Chandrachud was expected to deliver before his retirement was the constitutional validity of the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004.

The Act regulated the functioning of madrasas in the state and aimed to ensure quality education. A three-judge Bench led by CJI Chandrachud had reserved its verdict on the issue on October 22.

On April 5, the Apex Court had stayed an order of the Allahabad High Court that declared the Act as unconstitutional on the grounds that the High Court’s views appeared to be prima facie incorrect.

On March 22, the High Court declared the Act as unconstitutional, saying that a secular State had no power to create a board for religious education or to establish a board for school education only for a particular religion and create separate education systems for separate religions.

It further said that the Act violated Articles 21 (right to life and liberty) and 21A (right to free and compulsory education for children between 6 and 14 years) of the Constitution.

The Uttar Pradesh government had said that it stood by its Act and that the Allahabad High Court was wrong in declaring the entire law unconstitutional.

The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), however, described Madrasas as an “unsuitable and unfit” place to receive ‘proper’ education. It submitted in the Supreme Court that Madrasas not being schools — as defined under the Right to Education Act, 2009 — have no right to compel children or their families to receive Madrasa education.

Another critical issue, which a nine-judge Bench led by CJI Chandrachud was likely to decide this week, was whether the Government could requisition private property and redistribute it for public good.

On May 1, the Bench reserved its verdict on whether private properties could be considered ‘material’ resources of the community within the meaning of Article 39(b) of the Constitution and consequently, taken over by the State to subserve the common good.

Article 39(b) in the Directive Principles of State Policy says the State shall, in particular, ‘direct’ its policy towards securing that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community were so distributed as best to subserve the common good.

The issue also involved interpretation of Article 39(c), which said the operation of the economic system did not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment.