Above: Most legal journalists would be jobless if observations made by judges during court proceedings are not to be reported. Photo: Anil Shakya

The decision of the Delhi High Court to frame rules for journalists reporting court proceedings is welcome and could help improve the profession

~By Venkatasubramanian

Journalists don’t like to be told how to report by non-journalists. But in the absence of self-regulation within the media, the decision of the Delhi High Court to frame guidelines on how to report court proceedings should help evolve better standards in this profession.

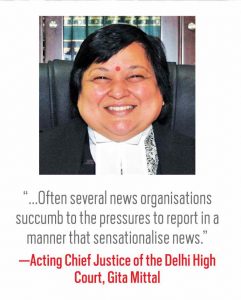

Acting Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, Gita Mittal, according to reports, has set up a committee of experts including judges, lawyers and a legal academic. The panel, to be chaired by former Supreme Court judge, Justice Ruma Pal, has a mandate to “recommend guidelines for media personnel and organisations to follow while reporting court cases and proceedings”. The committee has also been asked to come up with training modules for court reporters.

Justice Gita Mittal put the issue succinctly: “The current state of news reporting in India is such that often several news organisations succumb to the pressures to report in a manner that sensationalise news. There is a growing tendency to selectively report isolated court observations without reference to context.”

She added, “Even slightly erroneous reporting can seriously affect the fairness of court proceedings and the lives of those involved, disproportionately influencing the opinion of the public.”

SC DIFFERS

Hopefully, the committee set up for the purpose, would examine whether its terms of reference would be inconsistent with the decision of the Supreme Court’s constitution bench in the Sahara India Real Estate Corporation v Securities and Exchange Board of India, delivered on September 11, 2012. The Supreme Court, in this case, refrained from laying down guidelines for media in reporting criminal trials and sub-judice matters to ensure that there is balance between the right to freedom of expression of the media and the right to fair trial.

Hopefully, the committee set up for the purpose, would examine whether its terms of reference would be inconsistent with the decision of the Supreme Court’s constitution bench in the Sahara India Real Estate Corporation v Securities and Exchange Board of India, delivered on September 11, 2012. The Supreme Court, in this case, refrained from laying down guidelines for media in reporting criminal trials and sub-judice matters to ensure that there is balance between the right to freedom of expression of the media and the right to fair trial.

The Supreme Court, however, had laid down that aggrieved parties in a case could seek postponement of publication of reports on court hearings if it was felt that the reports could cause prejudice to the outcome of the case. The Court held that what constitutes an offending publication would depend on the decision of the court on a case-to-case basis. Framing across the board guidelines, it was felt, would be counter-productive.

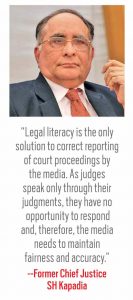

Former Chief Justice SH Kapadia, who headed the constitution bench in the Sahara case, had once stated that legal literacy is the only solution to correct reporting of court proceedings by the media. As judges speak only through their judgments, they have no opportunity to respond and, therefore, the media needs to maintain fairness and accuracy, he had said.

JUDGES DISSATISFIED

Judges have often expressed dissatisfaction with the media reporting utterances or observations which they make during court proceedings, even if they are newsworthy. According to some of them, such observations don’t reveal anything, not the least their intentions in making such remarks.

Judges make observations, it is pointed out, just to provoke the counsel and elicit their views. Therefore, attributing such tentative views to the judges or to the courts to which they belong to may not be entirely accurate, it is pointed out.

Journalists, however, may ask that if they are not to report observations, why should they sit through the hearing of important cases. If court reporting is just culling out the operative parts of judgments and summing up the arguments of respective parties as carried in their written submissions, most legal journalists would lose their jobs as the same can be done without visiting the court.

Journalists, however, may ask that if they are not to report observations, why should they sit through the hearing of important cases. If court reporting is just culling out the operative parts of judgments and summing up the arguments of respective parties as carried in their written submissions, most legal journalists would lose their jobs as the same can be done without visiting the court.

Reporting off-the-cuff remarks by judges and giving them sensational headlines may not be the correct way of reporting the proceedings, but is there an alternative? If the media could not ignore, at least it should understand and let the readers appreciate the context in which such observations are made.

There are judges who are articulate and offer a tentative view during the proceedings, rather than remain silent. While this gives an idea of what they may write in their judgments, attributing such views to the judges during the proceedings could make their judgment-writing a challenge, as they can’t change their views after the hearing is concluded. Otherwise, readers are likely to discover an inconsistency between their views during and after the hearing.

INFORMED DISCOURSE

Of the nine judges of the Supreme Court’s constitution bench who heard the right to privacy case recently, only three or four were very vocal, and could be seen making observations and interrupting the counsel who was making submissions, in order to clear their doubts. Obviously, these judges could not be said to have spoken on behalf of the remaining judges on the bench, who were more or less silent. But the observations of the judges and the replies of the counsel during the hearing are important to identify and debate the issues and controversies to ensure that there is an informed discourse in the media on the subject.

The sub-judice rule, therefore, cannot be stretched to mean a ban on all sort of public discourse on a pending case. The rule is based on the assumption that judges are likely to be unconsciously influenced by reading views in newspapers on cases which are pending before them. But then, judges may also benefit from reading such views so that they may include facets of the debate while writing the judgments.

In the debate on the right to privacy case, views were freely expressed both within and outside the court. Surely, the judges hearing the case may choose to ignore the views expressed in the media and confine themselves strictly to the proceedings to ensure objectivity. But if they allow themselves to be unconsciously influenced by the media views, this need not be deprecated. After all, judges are a part of society and their judgments may reflect the diversity of views articulated or missed by the counsel during the hearings.

One hopes that the proposed guidelines help the media to adopt better standards of court reporting without compromising the freedom of expression and professional objectives which they are expected to uphold.