Above: A demonstration for women’s rights. Photo: Anil Shakya

Here’s a comparison between the views of male feminists and men’s right groups on the issue of marital rape

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

No means no, and a rape is a rape. These are the two mantras anti-rape campaigners swear by. Both also sum up the case against marital rape, variously known as spousal rape, currently being heard in the Delhi High Court.

Petitioners—NGO RIT Foundation, the All India Democratic Women’s Association and two individuals, Abdulla Khan and Khushboo Saifi—are seeking to abolish marital rape by appealing against Exception 2 of Section 375 of the IPC. The Exception states that “sexual intercourse by a man with his wife, the wife not being under 15 years of age, is not rape”. It is one of two exceptions listed in the rape law, the other being that a “medical procedure or intervention” will also not constitute the offence.

The centre has submitted that defining marital rape would destabilise the institution of marriage. Interestingly, the Forum to Engage Men (FEM), which works for women’s rights, has intervened on the side of the petitioners, while Men Welfare Trust (MWT), a men’s rights group, has sided with the government.

So are men’s rights and women’s rights in conflict with one another? Is equality of the sexes a zero-sum game? The two stakeholders have found themselves on opposite sides of the courtroom on this matter.

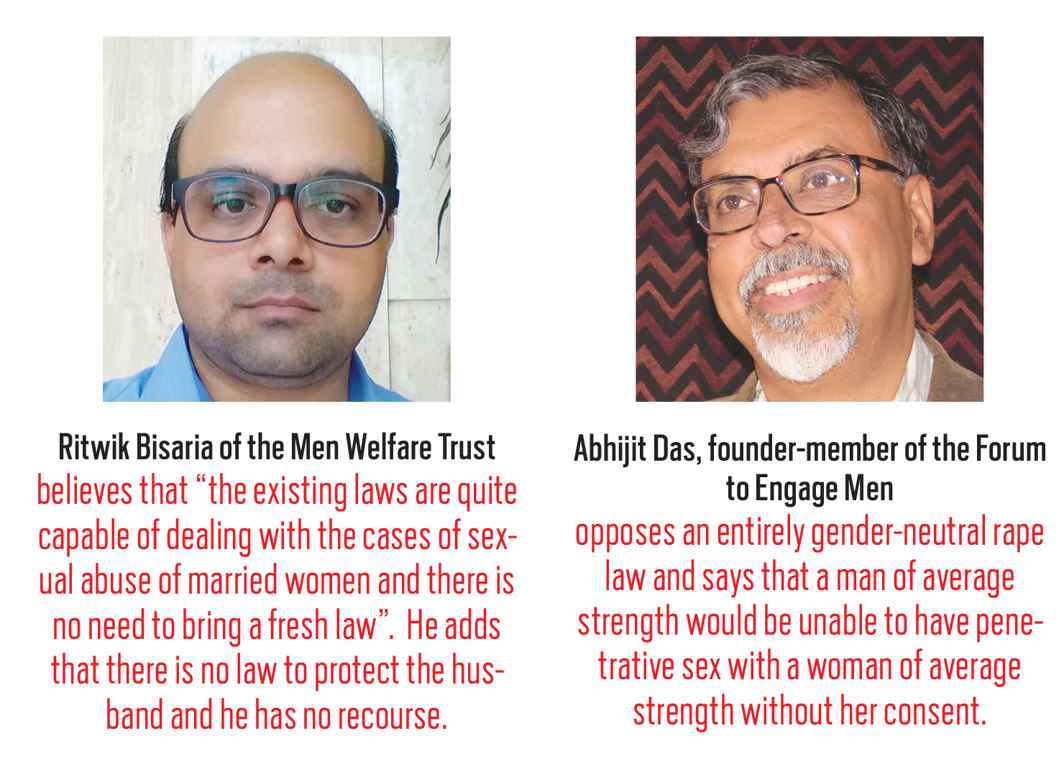

Abhijit Das, founder-member of the Forum to Engage Men (FEM) and an obstetrician-gynaecologist and rural health professional, like most doctors, has been among the traditional champions of women’s rights in India. Armed as he is with both scientific knowledge and a humanitarian outlook, he is uniquely positioned for this work. Launched in 2007, FEM is a loose network of several frontline feminist organisations—Ahsas Social Organisation, Durbar Mahila Samanvaya Samiti, Jagori, and Men Against Violence and Abuse… It educates boys and men about the women’s situation in India.

Das said that the exception they are seeking to strike down is contradictory to the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO) 2012. The IPC “excepts” rape of a wife above 15 years of age, but the POCSO Act criminalises sexual acts with “children” who constitute those below the age of 18. It is also anomalous with respect to the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act 2006 which holds a child marriage voidable, though only upon the filing of a petition for annulment in the court by the minor before he/she has completed two years of attaining majority. This is even as consensual sex with anyone below the age of 18 outside marriage is deemed statutory rape.

Das’ stance is rooted in social reality. He said: “Our opponents, including some men’s rights groups, feel that outlawing marital rape will lead to wives going to the police station at the drop of a hat. In Indian society, a wife bringing about such a complaint against her husband indicates that she is desperate. In the rare case her grievance happens to be frivolous, it means she wants the relationship to end. In such an eventuality, why should the husband want to hold on to it? I wonder what kind of a relationship that is.”

GENDER-NEUTRAL LAWS

Asked about rarer instances when the husband is a minor, but the wife is not, as seen in the recently-pulled TV show, Pehredaar Piya Ki, he said that these cases too would fall under the POCSO Act. And this is the reason why Das opposes an entirely gender-neutral rape law. He concedes that a man of average strength would be unable to have penetrative sex with a woman of average strength without her consent unless some external force or coercion is present, such as fear, a weapon or a third party.

But he points out that marital rapes are still fairly common in India as statistics say that 10 percent of Indian women have suffered sexual violence. Further, women are usually under immense pressure from the family and society to endure it for the sake of appearances, peace, security and children’s well-being. He pragmatically says that “at this stage, equity is more important than equality” and as long as women continue to be at a significant disadvantage as a group, additional protections need to be there for their empowerment and equality. He insists, though, that outlawing marital rape of women should logically make the law more equal, than less, for the sexes.

The MWT plea states that “the concept of marital rape cannot apply in the Indian context” wherein marriage is treated as a sacrament rather than a contract.

“Equality without substantive equity is not possible. In an unequal situation, you must act as the enabler for those being subordinated. That is equity. Today, privileges are with men and women need to be empowered; so we have to push the establishment to move in that direction,” Das said.

EXISTING LAWS

Meanwhile, there is the Men Welfare Trust (MWT) which was registered this year by Amit Lakhani and Ritwik Bisaria. They believe that “the existing laws are quite capable of dealing with the cases of sexual abuse of married women and there is no need to bring a fresh law”.

These laws are the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, which covers sexual violence, the dowry law or Section 498 of the Indian Penal Code which protects wives against cruelty, Section 377 which gives them protection against unnatural sex and Section 376B which sets out a two- to seven-year jail sentence for a man raping his wife, either separated from him by a legal decree or otherwise living separately from him.

Bisaria goes on to highlight how there is no law to protect the husband and in case of violence at home, he has no recourse. He also makes a convincing argument regarding male rape, saying it is a reality unrecognised in India and it covers all forms of sex forced on men, of which anal rape is one category. He sp-eaks of a well-reported case in 2014 in Delhi wherein three women tried to force themselves on an auto-rickshaw driver who jumped from the balcony in order to get away from them, fracturing both his legs.

“We have 49 laws today that are based on gender,” Bisaria said, making a case for a gender-neutral rape law. He puts forward a 2007 study on child sexual abuse by the women and child department that shows 53 percent of the victims were boys. Asked why he is against the striking down of Exception 2, he said he is opposed to forced sex, but “the moment the term rape comes into marriage, it undermines it and leads to a lot of unnecessary complications”.

Exception 2 of Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code states that “sexual intercourse by a man with his wife, the wife not being under 15 years of age, is not rape”.

He fears that should such a change come about, the chances of its misuse would be so high that “innocent husbands would be left with no remedy and would be subjected to cruelty on the part of wives”. His attitude sadly betrays a lack of trust in the opposite sex. The MWT plea also states that “the concept of marital rape cannot apply in the Indian context” wherein marriage is treated as a sacrament rather than a contract. Is this a rather romantic notion or driven by cultural precepts and patriarchy?

Asked about the feminist movement, which has contributed much to the cause of social justice, Bisaria said: “Any movement that seeks to replace one inequality with another is a wrong movement.” His answer clearly shows he favours status quo on the issue.

CHILD MARITAL RAPE

Interestingly, what Bisaria, and his predecessor Supreme Court advocate Ram Prakash Chugh, have done has actually helped the women’s cause. They have raised some questions which haven’t been asked or addressed by the feminist movement. Chugh told India Legal that while he supports the outlawing of child marital rape, “the exception should be present but adolescents should be protected. In case of adults, things are different, as they can handle themselves”. He seems to believe in the self-sufficiency and independence of women.

He, however, scoffs at the “no means no” argument, saying that no sometimes means yes, as it forms part of common courting behaviour. Chugh has brought to focus a social reality that women need to factor in when defending themselves against rape.

Bisaria also mentions the element of unwanted seduction in some cases of male rape, which also applies to women victims. Women rape victims usually resist the notion of having been seduced by the rapist as it invites stigma.

These are different kinds of rape and need to be considered in discussions of this crime.