In a landmark judgment, the Delhi High Court has expanded the nature of fundamental rights by making the parents of a girl liable for violating her rights and has asked them to pay her compensation of Rs 3 lakh

~By Venkatasubramanian

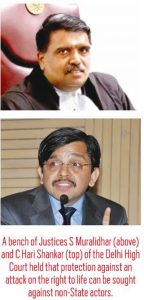

In April 18, a bench of Justices S Muralidhar and C Hari Shankar of the Delhi High Court, while deciding the case of Dr Sangamitra Acharya v State (NCT of Delhi) and Others, held that protection against an attack on the right to life, liberty, privacy and dignity can be sought not only against the State but against non-State actors.

“Article 21 places an obligation both on State and non-State actors not to deprive a person of life, liberty, privacy and dignity, except in accordance with the procedure established by law. In other words, Articles 15(2), 17, 19, 21 and 23 acknowledge the horizontal nature of those rights. They can be enforced against not just the State, but non-State actors as well,” the High Court held in its judgment.

The bench held that the Court should not hesitate to exercise its jurisdiction to grant relief if the plea in a habeas corpus petition is to protect a person against coercive retributive action of her parents for making personal life choices. In effect, the Court recognised that the threat to the right of choice of a person and thereby right to life, liberty, privacy and dignity can very well come from the person’s own parents, irrespective of the age and gender of such a person.

BIZARRE CASE

In the present case, a teacher of classical music and his wife sought a writ of habeas corpus, in light of the right to life, liberty, dignity, and in light of the right to privacy and autonomy of an adult female, aged 23 years, whom the Court referred to as “Z” in order to protect her privacy.

The girl was staying with the petitioners since she was 18 and forcibly taken away at the behest of her parents and brother with the help of the local police and an ambulance service. She was taken away to a privately-run mental hospital and kept there without her consent for two days.

The High Court concluded that the forcible taking away of Z from the residence of the petitioners and her consequent detention were illegal, unconstitutional and violative of her fundamental rights to life, liberty, dignity and privacy under Article 21 and Section 19 of the Mental Health Act, 1987 (MHA), which has now been replaced by the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. Section 19 of the 1987 Act, which was not yet repealed when this incident occurred, deals with admission of mentally ill persons under certain circumstances in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric nursing home.

Z had been learning Hindustani classical music from both the petitioners since she was 11 years old and was deeply interested in pursuing a career in classical music. As Z was unable to get along with her parents and her brother, she voluntarily moved in with the petitioners when she was 18. Her parents then alleged that their daughter had been enticed by the petitioners who had an undue influence on her from the time she was a minor.

They further alleged that their daughter suffered from a serious mental disorder which required medical care and treatment. They prayed that their daughter should remain under their care and control. Their complaint was dismissed by the Metropolitan Magistrate in 2015, after being satisfied that Z was not suffering from any mental illness and that she left the house of her parents after she became a major.

They further alleged that their daughter suffered from a serious mental disorder which required medical care and treatment. They prayed that their daughter should remain under their care and control. Their complaint was dismissed by the Metropolitan Magistrate in 2015, after being satisfied that Z was not suffering from any mental illness and that she left the house of her parents after she became a major.

In 2016, the parents again approached the High Court, asking that they should be appointed guardians of Z. During the pendency of this case, Z was examined by a panel of doctors at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, who also ruled out that she was suffering from any mental illness. Test findings indicated that the patient suffered from a great deal of stress as well as anxiety owing to the “family conflict she is having”. In the light of this report, the parents withdrew their writ petition in the High Court.

What happened in June 2017 was bizarre. With the help of the police and a private ambulance service, the petitioners’ home was ransacked and Z’s possessions and documents were forcibly taken by her parents and brother, who had concealed the facts of the earlier Court orders confirming that Z did not suffer from any mental illness. Z was forced onto a bed by two or three men (unidentified) and forcibly injected with a substance that caused her to faint, and later taken in an ambulance to a mental hospital. The music teacher, who was 69 years old, was beaten and bound.

BLATANT VIOLATION

Section 19(1) of the MHA, 1987, requires an application be made by a relative or friend for the admission of a mentally ill person in a mental hospital. Under Section 19(2), the application has to be accompanied by medical certificates from two medical practitioners, one of whom has to be a medical practitioner in government service. The certificate should be to the effect that the condition of a mentally ill person is such that he or she should be kept under observation and treatment as an in-patient in a psychiatric hospital. The High Court found that the procedure under Section 19 was clearly not followed.

The Court noted that a patient cannot be admitted merely for observation under Section 19(2) of the MHA. A patient has to be admitted for both observation and treatment, it held. Taking serious note of the incident which occurred on June 11, 2017, the Court had, on June 13, 2017, directed that Z be allowed to go back to the home of the petitioners, without any hindrance from any quarter. She was also afforded police protection. The parents gave an undertaking that they would not harass Z hereafter.

The Court also ordered that an exhaustive inquiry be conducted under the direct supervision of the Commissioner of Police. In its judgment, the High Court emphasised that Z was an adult, entitled to make her own life choices. She could decide whom she wanted to live with and where; her parents could not dictate to her where, with whom and how she should live, it held.

Relying on the recent Supreme Court’s nine-judge bench judgment on the right to privacy, the High Court held that Article 21 places an obligation, both on State and non-State actors, not to deprive a person of life, liberty, privacy and dignity except in accordance with the procedure established by law. In other words, Articles 15(2), 17, 19, 21 and 23 acknowledge the horizontal nature of those fundamental rights, which means that they can be enforced against not just the State, but non-State actors as well. The horizontal dimension of these rights enables an aggrieved person to invoke constitutional remedies to seek the protection and enforcement of such rights against invasion by a non-State actor.

The Court noted that increasingly, in the habeas corpus jurisdiction, it is approached by a large number of individuals and married couples praying for protection against invasion of their rights to life and liberty and choice by close relatives and other non-State actors.

Relying on the Supreme Court’s recent judgments in the Hadiya and passive euthanasia cases as well, the Delhi High Court noted that trouble started for Z when she began to exercise her personal choice as regards her career and consequently, her place of residence. Z’s parents, the Court said, are under a mistaken assumption that “in case of a daughter, she remains dependent on her parents till she gets married, irrespective of the fact that whether she has attained majority or not”.

The High Court emphasised that having attained the age of majority, Z can exercise her free will.

VIOLATING RIGHTS

The High Court, therefore, found that Z’s parents had violated her fundamental rights to life, liberty, privacy and dignity in collusion with the police, the ambulance service and abetted by the mental hospital. It held that a professional psychiatrist requires personal interaction with a person before making a diagnosis of her mental condition. Taking serious note of the doctors determining her mental state by merely discussing the symptoms over the telephone, the Court directed formulation of a code of ethics by the Medical Council of India in this regard.

The High Court also expressed concern that the ambulance staff who forcibly removed Z did not satisfy themselves that she was suffering from mental illness. They acted on the basis of a three-year-old certificate to determine that she was incapable of taking her own decisions. It asked whether the ambulance was registered as per the guidelines, which require a medical control physician to give an undertaking that he shall be responsible for maintaining the quality of the service provided in the ambulance.

The Court said the ambulance staff grossly neglected the duty of care owed to Z. They proceeded to abet her abduction and administered drugs to her by injection in the absence of any medical records and on the mere say of Z’s family. This is a fit case for revocation of the registration of the ambulance company, the High Court held.

It also found the head constable, who was a witness to Z’s abduction, guilty of dereliction of duty in protecting the life and liberty of a citizen. The Court wondered why no disciplinary action was taken against him. The bench also sought a probe against the sub-inspector, whether he was acting in a bona fide manner, for the delay in the registration of an FIR on the complaint of the petitioners.

The Court directed payment of compensation of Rs 3 lakh by the mental hospital, Rs 1 lakh by the ambulance company and Rs 3 lakh by Z’s parents to her.

Hopefully, the payment of compensation will act as a warning to those similarly violating fundamental rights.