While shifting the financial year cycle may require legislation for smooth transition, experts say the change shouldn’t be hasty and must not clash with the GST rollout

~By Ajith Pillai

Speaking at the NITI Aayog’s governing council meeting in Delhi on April 23, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made it abundantly clear that he favoured India shifting to a January to December fiscal year from the current April to March cycle which has been followed since 1867. The proposed change comes with some plusses and a few minuses, including the costs involved in shifting from one entrenched system to a new one.

Sources in the finance ministry told India Legal that an immediate change is unlikely since it would come as a “double disruption” to all concerned. Said an official: “At a time when the government, the tax authorities as well as the entire business community is gearing itself for the shock of the GST regime rollout, the change in the financial year (FY) will come as yet another major headache. The general consensus in the ministry is that the change in FY should happen but perhaps it may not be advisable to push things in a hurry when we have the GST rollout before us.”

Archit Gupta, CEO of ClearTax, a portal that advises business houses, said: “Any change in the financial year at this crucial time prior to the launch of GST may create additional challenges for businesses. A change could result in a transition period that may cause business disruption and slowing down. Until GST settles down, FY change should not be considered in the next two-three years.”

NO DEADLINE

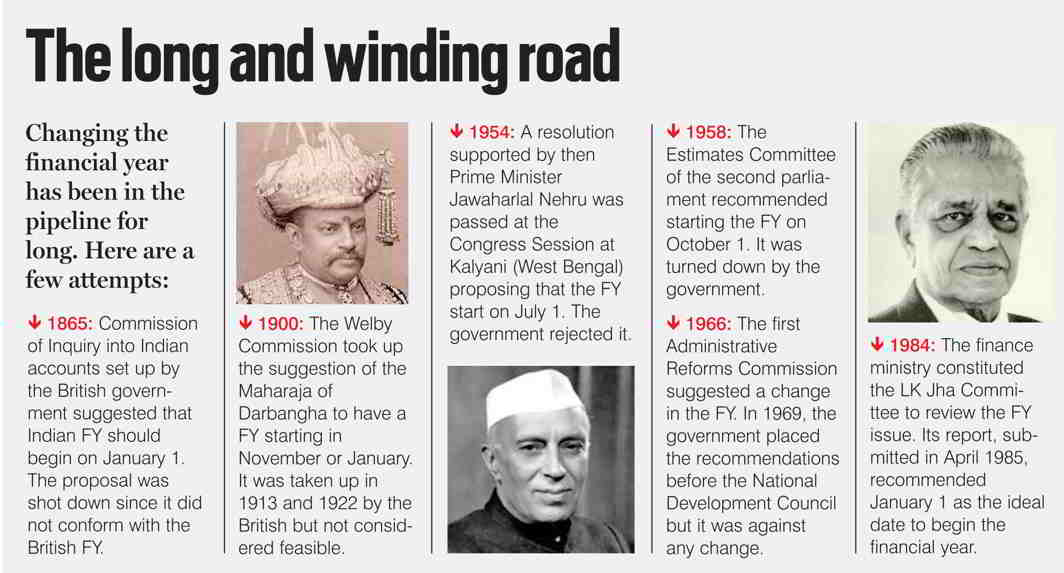

The Prime Minister did not set any deadline for implementing the new FY although one cannot predict if he will spring a surprise as he did with demonetisation. But as of April 23, he was merely echoing a suggestion that has been doing the rounds in the government for several decades (see box). More importantly, the need for a new financial year cycle has been on the agenda of the Modi government ever since the formation of the NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog on January 1, 2015, to replace the Planning Commission.

In fact, in July last year, the centre appointed a committee under Chief Economic Advisor, Shankar Acharya to examine the feasibility of changing the FY. Some states agreed, although Maharashtra objected. It felt that any change would be “needlessly disruptive to the state of Maharashtra at a time when fixing the economy and implementing GST and new financial norms should be the priority.”

A discussion note for NITI Aayog last year titled, “Need for Changing India’s Financial Year” by economists Bibek Debroy and Kishori Desai spells out in detail the need to shift from a budget system that was introduced seven years after the transfer of the Indian administration from the East India Company to the British Crown in 1860. “The present financial year in India (1st April to 31st March) was adopted by the Government of India in 1867 principally to align the Indian financial year with that of the British government,” says the note.

But the authors of the note also recognised that shifting to a new FY cannot happen overnight. They said a legislation may be required to bring about the change. They suggested introducing the New Indian Financial Year Act and getting it passed in parliament. The new legislation, they felt, should address the following:

- Define the new financial year and the “transitional financial year”

- Amend the definition of financial year in General Clauses Act 1896

- Detail appropriate changes to taxation and financial administration statutes and rules (including implications of recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission) for the “transitional financial year” and the procedures

- Detail changes in the statistical data collection and dissemination guidelines

- Facilitate similar changes to be adopted by state governments

REASONS FOR CHANGE

The key reasons cited for changing the FY were two. One, the January-December cycle will align with the common time-frame for budget years in most developed countries. This will be a clear positive as the Indian economy gets increasingly globalised. Also, ease of conducting business in India would significantly improve since MNCs will no longer have to deal with two financial years—one in their home country and the other in India. Said DK Joshi, chief economist at Crisil, a rating agency: “A change to the global practice is good. It will align our numbers with the rest of the world.”

Changing the FY will align with the time-frame for budget years in most developed countries and ease of conducting business would improve

At the domestic level, experts have long been recommending that a change in the FY is necessary to focus budgetary allocations in a country where agriculture plays a significant role in the economy. The South-West monsoon which sets in during May and retreats in July is the principal rainy season accounting for 75 percent of rainfall. It is followed in October-December by the South-East monsoon which covers coastal areas of Tamil Nadu. But both the kharif and rabi crops are impacted mainly by the South-West monsoon.

The timeline of the current budget is such that although finalisation of budgetary estimates happens in December-January, it is May by the time parliament and the president approve the Finance and Appropriation Bill.

As a result, when the new allocations finally reach the implementing agencies, it is May-end or June. That’s when the new South-West monsoon is about to kick in. So, the estimates and allocations arrived at with data from the previous year lose relevance.

As the NITI Aayog note points out: “From the perspective of monsoons, it essentially means that by the time Government authorizes fresh allocations, the impact of previous South-West monsoon is well over (more than 8 months over) and by the time fresh allocations reach implementing authorities (May/June)–the (new) South-West monsoon is just about to set in, thereby leaving no immediate space for course-corrections, if needed.”

UNDER-UTILISED FUNDS

It also points out that under the present system, much of the development and construction work for which monies is allotted in May/June is immediately halted because of the monsoon and is resumed in August/September. This means that implementation and utilisation of funds in the current FY cycle is limited and often under-utilised because the funds reach the implementing agencies when the monsoon is about to break.

The NITI Aayog paper acknowledges that the change would come with attendant teething troubles. To quote: “Any change in the financial year would cause in the short run considerable dislocation in the administrative and statistical fields of activity. But that consideration should not deter us from adopting a more rational, practical and convenient system, keeping in view the many advantages which will accrue therefrom…. Past experience in such matters shows that the process of adaptation to new systems superseding age-old practices will not be unduly protracted or painful.”

So, a change in the old colonial practice can be expected although it may not happen as soon as some would expect. Unless, of course the prime minister vigorously pushes for it. The UPA had also mooted changing the FY. But it could not pull it off before its second term in office concluded.