Above: Can the common man no longer expect a secure future?

The Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill 2017, cleared by the cabinet and before a parliamentary panel, will lead to a bail-in of unviable banks using depositors’ money. Will they be made to suffer in the name of national interest?

~By Ajith Pillai

After the shock and awe of demonetisation, the next word to be feared from the bulwark of the Union finance ministry is the relatively unheard of term—“bail-in”. This, its critics aver, is a provision that will shake the very foundation of public trust in the banking system. It is contained in proposed legislation, the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance (FRDI) Bill, 2017, which has been cleared by the cabinet and is currently before a parliamentary committee which will submit its report in the winter session of parliament.

So, what is a bail-in? In simple terms, it is a process by which a bank, rendered commercially unviable by mounting debts, squares its balance sheets by taking over a substantial chunk of its depositors’ money. Till now, we have heard of the government “bailing out” ailing banks. A “bail-in” is when depositors’ money is forcibly taken away from them by an act of law for the same purpose.

PANIC-STRICKEN

Section 52 of the proposed FRDI Bill incorporates the bail-in proviso and has set off panic among those who are aware of the larger implications of the new legislation. While a bank, riddled with mounting debts, can in future throw up its hands, those depositors who have reposed faith in it will have a lot to lose and pay for. The bill does not specify the quantum of depositors’ money that will be secure or safe when a bank runs into trouble but “it cannot exceed the insured amount”, which is currently fixed at Rs 1 lakh. So, for all the accounts and fixed deposits you hold in a bank or its branches, the combined total compensation entitlement will be a measly Rs 1 lakh.

Or, if the bank is kindly disposed towards its depositors, it can seize all their deposits—less Rs 1 lakh—and invest the money in bonds or other instruments without consent for a period of time at a nominal interest of five percent. But the bottom line is that depositors will have no access to their money beyond the insured amount of Rs 1 lakh.

Or, if the bank is kindly disposed towards its depositors, it can seize all their deposits—less Rs 1 lakh—and invest the money in bonds or other instruments without consent for a period of time at a nominal interest of five percent. But the bottom line is that depositors will have no access to their money beyond the insured amount of Rs 1 lakh.

Voices protesting the new law have been rather delayed given that the bill has been in the works since November 2014. But an online petition launched in the first week of December on Change.org by Mumbai-based Shilpa Shree had secured over one lakh signatures by December 12. It is primarily addressed to Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley and members of the parliamentary committee and implores the government not to use the money of “innocent depositors” to bail in mismanaged banks. Other voices have begun to surface on social media urging people to protest against the bill.

SMALL DEPOSITORS

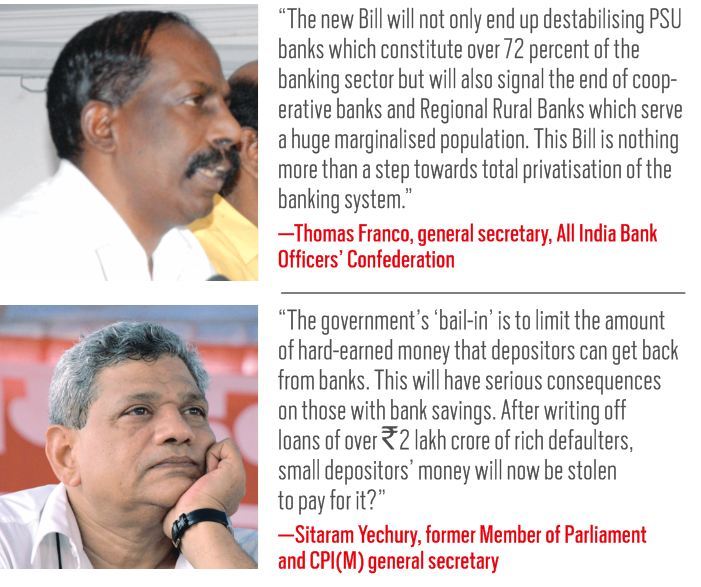

CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury has said that his party is opposed to the bill because small depositors will eventually be made to pay for the fault of banks. He said: “The government’s ‘bail-in’ is to limit the amount of hard-earned money that depositors can get back from banks. This will have serious consequences on those with bank savings. After writing off loans of over Rs 2 lakh crore of rich defaulters, small depositors’ money will now be stolen to pay for it?”

On his part, Jaitley has been at pains to allay the fears of depositors over the new bill. He has stated that the FRDI Bill is more “depositor friendly” than in other countries where the bail-in clause is currently operational. He has also been quoted as saying that the bill is likely to undergo changes. “The parliamentary committee can offer suggestions and thereafter it has to come back to the cabinet. The cabinet will put it in the public domain and ask for suggestions as well. So, I think a lot of corrections will take place,” he said. But this explanation has obviously not addressed public apprehensions adequately.

Not Homegrown

Was the FRDI Bill 2017 a brainchild of the government? Or was it inspired by a desi economist scrolling ancient Hindu texts for a solution to India’s ailing banking system? The controversial bill, it is reliably learnt, has nothing Indian about it.

In fact, it was kick-started in November 2014 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi attended the G-20 summit in Sydney. It was there that he committed India to implement a proposal drafted by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international body formed in 2009 after the global meltdown the previous year.

The FSB monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system. It had drafted a document—“The Key Attributes of Effective Resolution”—which it wanted other nations to adopt. It is this document that pushed for a system where sick banks are not bailed out by governments but “bailed in” by their depositors.

The FRDI Bill has the stamp of the FSB on it. A 10-member committee headed by Ajay Tyagi, additional secretary (investment), department of economic affairs, which drafted the bill, has acknowledged this in its introductory note. To quote: “The committee studied guidances issued by the Financial Stability Board and to the extent suitable, drafted the bill to be consistent with the key attributes given in those guidances.” The draft bill, according to sources in the finance ministry, is virtually borrowed from the FSB recommendations.

But critics of the bill point out that the FSB recommendations were drawn up by US experts with their own banking system in mind. A bank official said: “While in India, over 70 percent banks are government-owned, in the US they are all in the private sector. Moreover, American banks are run with maximising profits as their priority, while our banks also have a social responsibility to fulfil. Entirely different parameters and priorities are involved, so what suits them cannot suit us.”

According to him, sufficient homework was not done before drafting the bill. There was also the pressure from the FSB which was monitoring the progress of nations which had agreed to banking reforms during the G-20 Summit. It is perhaps to report progress that the draft bill was submitted to the government in September 2016 without consulting all the stakeholders, including bank unions and associations.

It now remains to be seen if the parliamentary committee studying the bill will recommend changes and whether these will be incorporated in the revised version of the proposed legislation.

A former finance ministry official told India Legal that such fears are not unwarranted: “Our trust in banks is based on the belief that whatever we deposit there is safe and can be withdrawn along with the accumulated interest. Generations of Indians have planned their lives based on the fiduciary trust we repose in our banks, particularly PSU banks. The fear is that with the passing of the bill confidence will be broken. Keeping money in a bank will come with a risk element which is a matter of concern in a country like India.”

He also feels that people have begun to take official assurances with a pinch of salt given the bad experience they have had with demonetisation and GST. “I have met people who are worried about the manner in which the bill will be implemented. They wonder if depositors will eventually be made to suffer in the name of national interest,” he said.

DEVELOPED WORLD PRACTICE

According to the government, the bill is very much in keeping with banking practice followed in the developed world post the 2008 global meltdown. According to it, taxpayers and the government must not be expected to absorb losses incurred by a bank through its financial failures. Shareholders and creditors must also bear the burden.

According to the government, the bill is in keeping with the practice followed in the developed world post the 2008 global meltdown. According to it, shareholders and creditors are expected to bear the burden of losses incurred by a bank.

This sounds reasonable and justified. But then, you have to also weigh in the following factors—quite unknown to people unfamiliar with banking operations: (a) as an account holder you are by definition a creditor, (b) monies deposited are like unsecured loans given by you to the bank, (c) the bank offers no security for your deposits, and (d) under the proposed regime you, along with shareholders, may have to forsake a part of your money should the bank fail.

Currently, it is the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation, under the Reserve Bank of India that insures depositors to a personal maximum of Rs 1 lakh. However, sources in the finance ministry reveal that this amount might be upgraded as and when the bill is tweaked. But would that be enough to inspire confidence among depositors? Or will bank deposits metamorphose from a safe investment to a risk-prone one?

Over the years, faith in banks and the Life Insurance Corporation of India was built on trust and confidence rather than on any explicit guarantee of safety. This was primarily because it was the RBI, and hence by extension, the government, which looked after the interests of depositors. But that will change as and when the bill is passed by parliament. The central bank’s role would then be limited to fixing interest rates, ensuring availability of currency and implementing the broader monetary policy. The key function of debt restructuring and dealing with sick banks and insurance companies will be the mandate of the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Corporation (FRDIC) which will be set up under the new legislation.

The proposed Corporation is one that will exercise its powers to order a bail-in as and when it deems fit. It can also recommend liquidation, merger or takeover of a financial institution if it finds it is financially unstable. Bank unions are opposed to the bill and the setting up of the FRDIC as they allege the latter will have sweeping powers and can be dictated to by the government.

FRDIC BOARD

As per the bill, the board of the FRDIC may have representation from the RBI, Securities and Exchange Board of India, the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India, and the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority. But six of the 11 members will be nominated by the government, giving it control over the Corporation and the crucial decision-making process.

The United Forum of Bank Unions has already written to Jaitley demanding that the FRDI Bill be withdrawn. “The objective of this bill is obviously to heavily empower the new authority [FRDIC] with sweeping powers to dismantle and erase public sector financial institutions like banks and insurance companies and hence, it is apparently draconian. We demand the withdrawal of this bill,” said its representation.

Thomas Franco, general secretary of the All India Bank Officers’ Confederation, raised another concern. He told India Legal: “The new bill will not only end up destabilising PSU banks which constitute over 72 percent of the banking sector but will also signal the end of cooperative banks and Regional Rural Banks (RRBs) which serve a huge marginalised population. I see this bill as nothing more than a step towards total privatisation of the banking system. You have one authority, the FRDIC, to declare a bank as being sick. Then the same authority will have the powers to take over the sick bank and hand it over to another entity which will most likely be in the private sector. This may not happen immediately, but it is bound to happen.”

According to him and others, the FRDI Bill seems to be a move by the government to undo bank nationalisation that was introduced in 1969. That is when the government of the day took over banks and decided that public sector banks and financial institutions should also serve the marginalised and weaker sections and not merely run for profit.

BANK NPAS

Today, the once healthy banking sector is crippled with mounting debts and non-performing assets (NPAs). But who is responsible for this? According to the RBI’s latest Financial Stability Report, 88.4 percent of NPAs are due to large borrowers with exposure of Rs 5 crore or more. Also, 25 percent of these NPAs is the creation of 12 large borrowers and banks who liberally lent to them without due diligence. But should depositors be punished for the sins committed by others? “We are heading towards an unfortunate situation where the poor depositor has to bail out the big defaulters. This is most unfair,” said Franco.

The prognosis does not look encouraging for India which is a savings-based economy. In the absence of any reliable social security net, interest earned from bank deposits is what a vast section of people have so far relied on to tide over a rainy day or during their retirement. Where do they now invest their hard-earned money? All options, including mutual funds and playing the stock market, come with hidden risks.

By all indications, should the bill be passed, the days of putting your feet up and earning an assured income from your bank deposits will be over.