Last November, the prime minister shocked and surprised the nation with his note ban announcement. A year down the line, what is the verdict?

~By MG Devasahayam

Demonetisation is not the end but the beginning of a “long, deep and constant” battle against black money and corruption and will benefit the poor and the common man. This is what Prime Minister Narendra Modi told his parliamentary party colleagues in November 2016. The loyalists hailed it and passed a resolution endorsing his “great crusade!”

In one fell swoop 86.4 percent of the cash in circulation was declared invalid, thereby destabilising the economy with citizens running around like “headless chicken”, crowding before banks and begging for their own money. This raised several legal issues and the matter went to the Supreme Court. Nine critical questions were framed to be considered by a constitution bench in January 2017. Even as the public went through immense suffering and humiliation, these questions remained unanswered and the “demonisation of cash” became a fait accompli!

All that the exercise called demonetisation has done is to put a reasonably healthy and functioning economy through forcible dialysis taking out 86 percent of its blood and running it through “Digital India” machines.

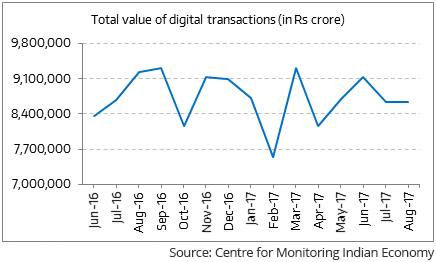

The moot question is if the objectives of demonetisation as given in the notification and declared by the PM have been achieved. As far as extinguishing fake currency and terror funding, clearly it was mere rhetoric. Both continue to flourish. On the elimination of unaccounted for wealth or black money, it turns out that more than 99 percent of invalidated currency came back into the banking system. Another objective was to aggressively promote “Digital India”. The central government, all departments, the RBI, NITI Aayog and commercial banks all pushed for “cashless business”. The PMO even decided to link all savings bank accounts with customers’ Aadhaar numbers to enable digital transactions. This was done in defiance of Supreme Court orders, to facilitate 30 crore people who do not own a phone, to join the digital economy and make online payments. Initially, players in the digital ecosystem, smart card manufacturers, payment gateway providers, electronic wallet companies, e-commerce platforms and telcos gained. But now, with cash transactions virtually returning to pre-monetisation days (see graph), this also does not sustain.

Nine Note Ban Questions SC will consider in January

The Supreme Court has referred the cases challenging the note ban to a constitution bench, while refusing to grant interim relief in the matter. It also framed nine questions for consideration by the bench in January.

- Does Reserve Bank of India (RBI) have the power to issue the November 8 notification to scrap Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes?

- Does demonetisation violate a citizen’s right to property under the constitution?

- Does demonetisation violate a citizen’s fundamental right to equality?

- Does capping withdrawal limit have a basis in law?

- Is the demonetisation scheme procedural and, otherwise, arbitrary?

- Is RBI’s power to scrap notes an excessive delegation of power by parliament?

- What is the scope of judicial review in fiscal and monetary policy?

- Can a political party file a writ petition in the Supreme Court against a government policy?

- Is the decision barring district cooperative banks from handling scrapped currency notes discriminatory?

Every time the RBI issues a currency note, it adds a liability to its balance sheet. By refusing to honour these notes as legal tender, the RBI extinguished its liability towards persons holding them, in effect enriching itself at the cost of its owner.

In the garb of “demonetisation”, the central government coerced the RBI to renege from its “promise to pay the bearer the sum of 1,000 and 500 rupees”. This violated Article 300A (right to property) and Articles 14, 19, 20 and 21 (fundamental rights) contained in the Constitution. This is also serious breach of trust. Every time the RBI issues a currency note, it adds a liability to its balance sheet. By refusing to honour these notes as legal tender, RBI extinguished its liability towards persons holding them, in effect enriching itself at the cost of its owner. This is expropriation, not demonetisation.

What is equally evident is that demonetisation has had a negative impact on the wages of the poorer segment of the population; badly undermining incomes of the farmer and informal sector entrepreneurs and imposing a burden of loss of purchasing power. This counters the PM’s claim of “benefiting the poor and the common man”. A UN report released in April 2017 says, “In terms of inequality India is only second to Russia where (in India) richest one percent own 53 percent of the country’s wealth.” Credit Suisse Group AG says that the percentage of country’s wealth held by the top one percent is around 58 percent. Job growth of just around one percent is dismal and underemployment is a staggering 35 percent of the over-15 years labour force. What is worse, over 30 percent micro and small businesses perished; leading to massive unemployment with the volatility rate rising sharply from 8.8 percent (pre-demonetisation) to 23.5 percent post-demonetisation.

What is equally evident is that demonetisation has had a negative impact on the wages of the poorer segment of the population; badly undermining incomes of the farmer and informal sector entrepreneurs and imposing a burden of loss of purchasing power. This counters the PM’s claim of “benefiting the poor and the common man”. A UN report released in April 2017 says, “In terms of inequality India is only second to Russia where (in India) richest one percent own 53 percent of the country’s wealth.” Credit Suisse Group AG says that the percentage of country’s wealth held by the top one percent is around 58 percent. Job growth of just around one percent is dismal and underemployment is a staggering 35 percent of the over-15 years labour force. What is worse, over 30 percent micro and small businesses perished; leading to massive unemployment with the volatility rate rising sharply from 8.8 percent (pre-demonetisation) to 23.5 percent post-demonetisation.

It is evident that none of the objectives of “demonetisation” has been met and the battle against black money and corruption has had little effect. All that this exercise has done is to put a reasonably healthy and functioning economy through forcible dialysis, taking out 86 percent of its blood and running it through “Digital India” machines.

—The writer is a former Army and IAS officer