Above: (L-R) Justice Kurian Joseph, Justice Jasti Chelameswar, Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice Madan B Lokur addressing a press conference in New Delhi/Photo: UNI

In a move that has shocked the nation, four senior judges of the apex court called a press meet to attack the chief justice and judicial procedures. By saying that democracy is in danger, they have exposed a rift in the Court which has alarming consequences

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

In a rebellion that has never been seen in the 70-year-old history of the Supreme Court, four of its senior-most judges came together on January 12 to launch a blistering attack against Chief Justice Dipak Misra. The scathing criticism by Justices J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph has opened a Pandora’s Box. Not only has their outburst severely undermined the hitherto untainted image of the highest court of the land but it has also provided fertile ground for an eager Executive to possibly interfere more aggressively in the functioning of the Supreme Court.

As is always the case with such an unprecedented move, the opinion on whether the “Rebellious Four” were right in voicing their grievances before a media that is notorious for exaggerating conflicts and letting their emotions get the better of their judgment, is sharply divided. Those in support of the four judges have justified their move by reiterating what Justices Chelameswar and Gogoi told the media—that they were paying a debt to protect the institution they serve. The naysayers have been quick to ask for their impeachment.

At least two facets of this rebellion are undeniable—the image of the highest judicial authority of the country has taken a severe beating and the integrity of a seemingly unimpeachable pillar of our democracy has been dented. What the four judges said about Chief Justice Misra can certainly not be dismissed lightly. Their allegations are damning and a signal of ominous times.

Addressing the media at his Tughlaq Lane residence in Delhi even as the chief justice was presiding over matters in the Supreme Court, Justice Chelameswar said that “it is with no pleasure that we’ve called this press conference”. He added: “The administration of the Supreme Court is not in order. Many things which are less than desirable have happened in the last few months.”

These opening remarks set the ball rolling for what quickly turned into a full frontal attack against the chief justice, stopping just short of calling for his impeachment, something the four judges said should be left for the nation to decide.

Justice Chelameswar made it clear that he and his three colleagues had decided to come before the media only after their collective effort to resolve issues with the chief justice—the latest having been made just hours before this interaction—had failed. “We tried to collectively persuade the chief justice that certain things are not in order and he should take remedial measures. Unfortunately, the measures failed… We were left with no choice except to communicate it to the nation that please take care of the institution… Unless the institution of Supreme Court is preserved, democracy won’t survive in this country,” he said.

It is well-known that tension had been simmering between Justice Chelameswar and Chief Justice Misra for a while now. Justice Chelameswar’s fellow “mutineers”, sources say, had also been peeved at being overlooked by the “master of the roster” (the chief justice) when assigning crucial cases to the benches. There were many flashpoints between them and the chief justice in recent months. Chief Justice Misra had famously overturned Justice Chelameswar’s order of constituting a five-judge bench in the “judges bribery case” and overlooked these senior judges in favour of junior ones in constituting the bench that will hear the crucial anti-Aadhaar linking petitions from January 17. He had also recalled an important order given by a two-judge bench on a petition challenging the delay in finalising the Memorandum of Procedure for appointment of judges in the higher judiciary (See Box on excerpts of the letter written by these four judges to the CJI).

Extracts from the four judges’ letter to Chief Justice Dipak Misra

- It is with great anguish and concern that we have thought it proper to address this letter to you so as to highlight certain judicial orders passed by this Court which has adversely affected the overall functioning of the justice delivery system and the independence of the High Courts besides impacting the administrative functioning of the Office of the Hon’ble Chief Justice of India.

- One of the well settled principles is that the Chief Justice is the master of the roster with a privilege to determine the roster, necessity in multi-numbered courts for an orderly transaction of business and appropriate arrangements with respect to matters with which member/bench of this Court (as the case may be) is required to deal with which case or class of cases is to be made. The convention of recognising the privilege of the Chief Justice to form the roster and assign cases to different numbers/benches of the Court is a convention devised for a disciplined and efficient transaction of business of the Court but not a recognition of any superior authority, legal or factual of the Chief Justice over his colleagues. It is too well settled in the jurisprudence of the country that the Chief Justice is only the first amongst the equals – nothing more or nothing less. In the matter of the determination of the roster there are well-settled and time honoured conventions guiding the Chief Justice, be it the conventions dealing with the strength of the bench which is required to deal with a particular case or the composition thereof.

A necessary corollary to the above mentioned principle is the members of any multi-numbered judicial body, including this court, would not arrogate to themselves the authority to deal with and pronounce upon matters which ought to be heard by appropriate benches, both composition wise with due regard to the roster fixed.

- We are sorry to say that off late the twin rules mentioned above have not been strictly adhered to. There have been instances where case having far-reaching consequences for the Nation and the institution had been assigned by the Chief Justices of this court selectively to the benches “of their preference” without any rationale basis for such assignment. This must be guarded against at all costs.

- In the above context, we deem it pro-per to address you presently with regard to the order dated 27 October, 2017 in P Luthra vs Union of India to the effect that there should be no further delay in finalising the Memorandum of Procedure in the larger public interest. When the Memorandum of Procedure was the subject matter of a decision of Constitution Bench this Court in Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association and Anr. Vs. Union of India [(2016) 5 SCC 1] it is difficult to understand as to how any other Bench could have dealt with the matter.

The above part, subsequent to the decision of Constitution Bench, detailed discussions were held by the Collegium of five judges (including yourself) and the Memorandum of Procedure was finalised and sent by the then Hon’ble the Chief Justice of India to the Government of India in March 2017. The Government of India has not responded to the communication and in view of this silence, it must be taken that the Memorandum of Procedure as finalised by the Collegium has been accepted by the Government of India on the basis of the order of this Court in Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (Supra). There was, therefore, no occasion for the Bench to make any observation with regard to the finalisation of the Memorandum of Procedure or that that issue cannot linger on for an indefinite period.

- Any issue with regard to the Memorandum of Procedure should be discussed in the Chief Justices Conference and by the full court. Such a matter of grave importance if at all required to be taken on the judicial side should be dealt with by none other than a Constitution bench.

The above development must be viewed with serious concern. The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India is duty bound to rectify the situation and take appropriate remedial measures after a full discussion with the other members of the Collegium and at a later stage, if required, with other Hon’ble Judges of this court.

The tipping point, however, seems to have come on the morning of January 12 when a politically sensitive petition concerning the mysterious death of special CBI judge BH Loya was referred to a bench headed by Justice Arun Mishra. Justice Loya was then presiding over the trial in the controversial Sohrabuddin Sheikh encounter case in which BJP president Amit Shah was an accused. Justice Mishra is known for his proximity to the chief justice and ranks far be-low the four rebels in seniority. Inciden-tally, Justice Mishra’s bench has been assigned several crucial cases by the chief justice, overlooking other benches headed by more senior and experienced judges, leading to muted accusations of possible nepotism.

Justice Gogoi stands to lose the most by his outburst as he is next in line for elevation as chief justice. Justice Chelameswar is set to retire in June, while the other two rebel judges, though his junior, will also retire within this year. Justice Gogoi said unambiguously that assigning of the Judge Loya case acted as the proverbial last straw. Many have been stunned that the rebels included Justice Gogoi as this revolt could effectively nip his chances of becoming chief justice. This is not a risk that most judges of the Supreme Court would find worth taking.

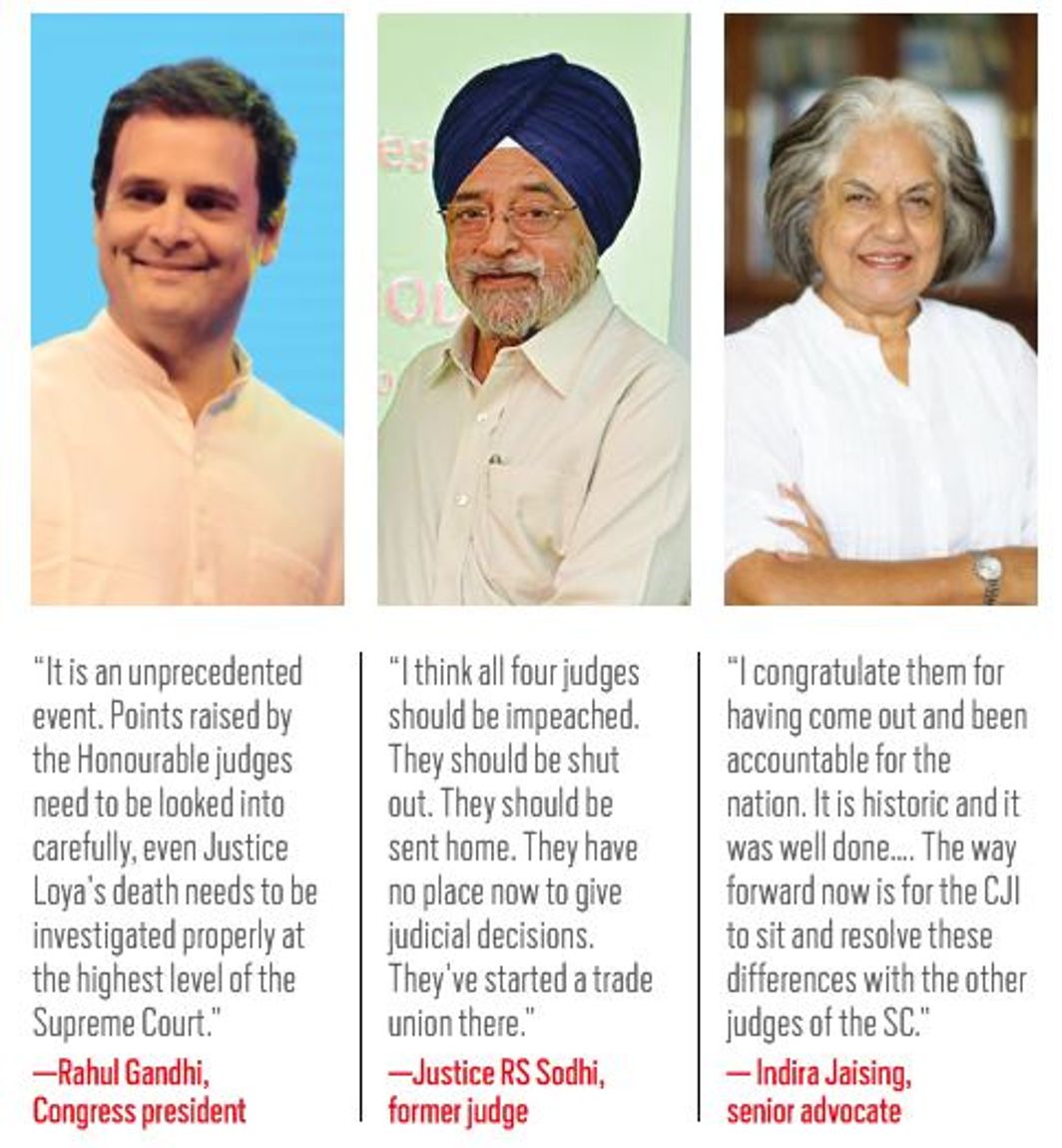

Reactions by the legal fraternity and the political brass to this tumultuous event have been varied. Sensing another opportunity to put Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government on the mat over the issue, the Congress was prompt to latch on to Justice Chelameswar’s criticism and assert that “democracy is in danger”. Congress president Rahul Gandhi told the media: “It is an unprecedented event. Points raised by the Honourable judges need to be looked into carefully, even Justice Loya’s death needs to be investigated properly at the highest level of the Supreme Court.” His party’s media cell chief Randeep Surjewala added: “The Congress Party is deeply perturbed by these developments… We earnestly appeal that the Full Court of the Supreme Court should take up the issues raised by the four Honourable judges and find solutions that are consistent with the traditions and conventions of the judiciary and that will preserve the independence of the judiciary.”

Justice Jasti Chelameswar

Date of appointment: October 10, 2011

Date of appointment: October 10, 2011

Date of retirement: June 22, 2018

Justice Jasti Chelameswar was born on June 23, 1953, in Krishna District of Andhra Pradesh. After completing his schooling from Hindu High School at Machilipatnam in Krishna District, he graduated from Loyola College in Chennai in physics. He graduated as a lawyer from Andhra University, Visakha-patnam, in 1976. Soon after being designated as a senior counsel, Justice Chelameswar was appointed as additional advocate general on October 13, 1995. Within a short span of two years, he was elevated as additional judge in the High Court of Andhra Pradesh. He was made chief justice of Gauhati High Court in 2007 and later transferred to Kerala High Court, where he became chief justice on March 17, 2010.

He has often been the main dissenting voice in the Supreme Court and was the main judge who criticised the Collegium system. In October 2016, he became the lone judge on the five-judge Constitution Bench led by Justice JS Khehar, which scrapped the National Judicial Appointments Commission law. He often chose to opt out of Collegium meetings. He was also a member of the three-judge bench which confirmed that the Aadhaar card is not compulsory. In 2014, he wrote a dissent note against holding open court hearings to review petitions of death row convicts. Along with Justice Rohinton F Nariman, he gave a landmark ruling on civil liberties and right to freedom of speech in the Shreya Singhal case.

Justice Ranjan Gogoi

Date of appointment: April 23, 2012

Date of appointment: April 23, 2012

Date of retirement: November 17, 2019

Justice Ranjan Gogoi was born on November 18, 1954, in Assam. He joined the Bar in 1978 and practised mainly in Gauhati High Court where he was appointed a judge in 2001. In 2010, he was transferred to Punjab and Haryana Court and made chief justice of the Court the next year. On April 23, 2012, he became a judge in the Supreme Court.

Justice Gogoi will be the senior-most judge when Chief Justice Misra retires and is most likely to succeed him later this year. If he does so, he will be the first CJI from the North-east.

One of his best known judgments was that a woman cannot be the karta of a joint family, but she can be its manager.

He was also part of the bench that restrained publishing of photographs of political leaders in government-funded advertisements and which set aside a notification to include Jats in the Other Backward Classes list. He also led the bench which heard the sworn statement of a former CBI officer in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case.

Justice Madan B Lokur

Date of appointment: June 4, 2012

Date of appointment: June 4, 2012

Date of retirement: December 30, 2018

Justice Madan B Lokur was born on December 31, 1953. He graduated in History (Hons) from St Stephen’s College, Delhi in 1974 and got his LLB degree from Faculty of Law, Delhi University, in 1977.

He became an advocate on July 28, 1977, and practised in the Supreme Court and Delhi High Court. He became an Advocate-on-Record in the Supreme Court in 1981 after passing the exam and was appointed additional solicitor general of India in 1999.

His area of experience is civil, criminal, constitutional, revenue and service laws. He was appointed the editor of Indian Law Reports (Delhi Series) in 1983. He was also a standing counsel of the government. In February 1997, he was designated as a senior advocate and elevated to the Supreme Court on July 4, 2012. He is also a member of the Mediation and Conciliation Project Committee of the Supreme Court since its inception in 2005, a judge in-charge of the e-committee of the apex court and was a one-man committee to suggest improvements in the working of homes and organization under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection and Children) Act, 2000 and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Rules, 2007. Justice Lokur along with Justice UU Lalit, used to head a social justice bench formed by the SC in 2014, Although it was later shelved, it heard cases like the rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits, exploitation of children in orphanages in Tamil Nadu and monitoring of the Nirbhaya fund.

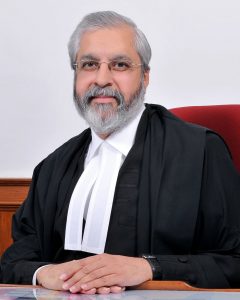

Justice Kurian Joseph

Date of appointment: March 8, 2013

Date of appointment: March 8, 2013

Date of retirement: November 29, 2018

Justice Kurian Joseph was born on November 30, 1953, and was educated in various schools and colleges in Kerala. He also studied in Kerala Law Academy Law College, Thiruvananthapuram and started his legal career in 1979 as part of the academic council of Kerala University. He served as a government pleader in 1987 and additional advocate general from 1994 to 1996. In 1996, he was designated a senior advocate. In 2000, he was elevated to Kerala High Court as a judge. From 2006-08, he served as president of the Kerala Judicial Academy. He twice served as acting chief justice of the Kerala High Court before being elevated as chief justice of the Himachal Pradesh High Court. On March 8, 2013, he became a judge in the Supreme Court. He believes that as people have high hopes from the judiciary, it must pro-actively participate in the delivery of justice.

He decided notable cases such as coal allocation, death penalty for Afzal Guru and triple talaq. In 2014, he told a 92-year-old litigant in an open courtroom: “Judges do not depend on their Chief Justice of India for courage to serve without ‘fear or favour’, they derive it from the Constitution of India.”

The centre has chosen to stay silent on the controversy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi reportedly discussed it with Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, following which government sources said that the Executive wants the issue to be treated as an “internal matter of the judiciary”. The centre’s highest law officer, Attorney General KK Venugopal, while admitting that the press interaction by the judges “could have been avoided”, also underscored: “You can take it from me that the whole of the differences will be settled in the next few days. You wait till day after tomorrow (Sunday).” He added: “The judges will now have to act in statesmanship and ensure that the divisiveness is wholly neutralised and total harmony and mutual understanding will prevail in future (sic).”

It was on May 7, 1997, that the Supreme Court in its Full Court adopted a Charter called the “Restatement of Values of Judicial Life” to serve as a guide for judges. The resolution expressly forbids members of the judiciary from entering into a public debate “on political matters or on matters that are pending or are likely to arise for judicial determination” and against giving interviews to the media.

While many legal and political luminaries who have criticised the four judges for their outburst claim that violating the “Restatement Resolution” and dragging the CJI into an ugly public de-bate are grounds for contempt charges being slapped against them, others like BJP veteran Yashwant Sinha said: “When national interest is at stake, the ordinary rules of business do not apply.” Indeed, Justice Chelameswar himself told the media: “We don’t want wise men saying 20 years from now that Justices Chelameswar, Gogoi, Lokur and Joseph sold their souls and didn’t do the right thing by our Constitution.”

While many legal and political luminaries who have criticised the four judges for their outburst claim that violating the “Restatement Resolution” and dragging the CJI into an ugly public de-bate are grounds for contempt charges being slapped against them, others like BJP veteran Yashwant Sinha said: “When national interest is at stake, the ordinary rules of business do not apply.” Indeed, Justice Chelameswar himself told the media: “We don’t want wise men saying 20 years from now that Justices Chelameswar, Gogoi, Lokur and Joseph sold their souls and didn’t do the right thing by our Constitution.”

The rebellion has sharply divided the legal fraternity. Retired Justice RS Sodhi was most unsparing in his criticism of the four rebels. “I think all four judges should be impeached. They should be shut out. They should be sent home. They have no place now to give judicial decisions. They’ve started a trade union there. There are four judges against the chief justice while 20 others serving in the Supreme Court are not. Is this a majority?” he asked.

However, senior advocate Indira Jaising welcomed the move by the rebels, stating: “I congratulate them for having come out and been accountable for the nation. It is historic and it was well done. The manner in which the four judges spoke was beautiful and as Justices Chelameswar and Gogoi pointed out—they did this not out of protest but because they have a debt to pay to the institution and the nation. The way forward now is for the chief justice to sit and resolve these differences with the other judges of the Supreme Court. However, I also wish to ask, why is there a divide?… Is there interference by the Executive (in the Court’s functioning)?”

The chief justice has so far refrained from commenting on this fiasco.

Former Acting Chief Justice of the Gauhati High Court K Sreedhar Rao, however, believes that the chief justice should not speak publicly on the controversy. “If the four judges have compromised the integrity of the Supreme Court by airing their grievances in public, it does not mean that the chief justice should do the same. He must discuss the matter internally and find a solution to this mess as him going to the press will only escalate matters and add to the noise,” he said.

It is still too early to guess how exactly this acrimony in the Supreme Court will end but what is certain is that a precedent has been set. However, the judiciary will best avoid a repeat of it if it wishes to retain the faith that the common man has in this pillar of democracy.