In a landmark order, the top court has reviewed the internet shutdown in Kashmir and upheld the need to protect constitutional guarantees and civil liberties

By Srishti Ojha

“As emergency does not shield the actions of Government completely; disagreement does not justify destabilisation; the beacon of rule of law shines always.”

—Justice NV Ramana

On January 10, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court comprising Justices NV Ramana, R Subhash Reddy and BR Gavai gave its final judgment on the multiple writ petitions filed against the Kashmir lockdown and laid down certain directions regarding restrictions placed under Section 144 of the CrPC.

The order drew attention to the provisions of this Section. Multiple orders have been passed by the government on multiple occasions regarding this Section. On August 5, 2019, a constitutional order was issued by the president revoking the special status of J&K and applying all provisions of the Constitution of India to the state. Due to the circumstances, the district magistrate imposed restrictions on movement and public gatherings, apprehending breach of peace and tranquility. Similarly, in December, there were multiple protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act in various cities. The government passed orders to restrict the protesters from gathering against or in favour of the law passed by Parliament.

Section 144 is a legal provision that gives the government the power to issue orders for immediate remedy in cases of emergency and apprehended danger. However, the government has faced criticism for these restrictions. A district magistrate, sub-divisional magistrate or any other executive magistrate can issue such an order to an individual or the general public in a particular place to “abstain from a certain act” or “to take certain order with respect to certain property in his possession or under his management”. Therefore, under this Section, people can be restricted from moving, having public gatherings, using the internet, and so on.

A crucial part is that the order can be passed only “if such Magistrate considers that there is sufficient ground for proceeding under this section, and immediate prevention or speedy direction is required to prevent ‘danger to human life, health or safety’, ‘obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed’, and ‘disturbance of the public tranquility, or a riot”. The duration of these restrictions cannot be more than two months. In situations where the state government feels that the restrictions are still required, the order can be extended to six months. When such an order is passed, a notice needs to be served to those who are being restricted and an opportunity to be heard needs to be given to them. However, in cases of emergency when there is no time to serve such a notice, an order can be passed ex parte.

This order also mentions the subjects the Section is imposed on and everything that needs to be done in order to prevent damage to life, health, property, etc. For example, an order by the government in Kashmir last year stated that “there shall be no movement of public and all educational institutions shall also remain closed, all public movement has been curtailed and educational institutions will remain closed”.

However, on numerous occasions, there have been accusations that this provision has been used stealthily, treacherously and deceptively and for conferring unlimited powers on the authorities. But there are also those who say that in exceptional times, exceptional measures are required.

Even though the Section places a check on magistrates to ensure that their powers are not unbridled, it is still criticised for giving them too much power as the onus to prove that urgent action is needed rests completely on their opinion and conscience.

This Section has also been criticised for being violative of fundamental rights such as the right to freedom of speech and expression. Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution provides the freedom to express one’s views and opinions, and has also been called the “Ark of the Covenant of Democracy” by the Supreme Court. However, that right is not absolute and can be restricted in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order and decency or morality, under Article 19(2).

The Supreme Court has time and again decided cases involving the question of validity of orders under this Section. In Madhu Limaye vs Sub-Divisional Magistrate (1970), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Section 144 on the grounds that it constituted a reasonable restriction in the interest of public order. Chief Justice Mohammad Hidayatullah had stated that if applied properly, the Section is not unconstitutional and the possibility of it being abused is no ground for it to be struck down.

In the case of Babul Parate (1961), the Court had held that power under Section 144 could be exercised in cases of both the presence of danger as well as its apprehension. The magistrate should be satisfied that immediate prevention is necessary to counteract danger to public safety.

In the Ramlila Maidan case (2012), the Court had stated that power under Section 144 must be exercised in the interest of public order, for public safety and tranquility. The threat should not be a mere perception but a definite and substantiated one.

And on January 10, the Supreme Court, while deciding the petitions challenging the constitutionality of the Kashmir lockdown, curtailment of movement and all forms of civil liberties, gave its final order which could help in seeing Section 144 in a new light. Though the order mostly focused on the importance of the internet and validity of the lockdown, it was relevant for two reasons: Firstly, restrictions were imposed on the internet under Section 144 and secondly, the Court gave directions on how power under this Section would be executed from now on. As part of the three-judge bench, Justice Ramana stated that an important question of law that arose for the bench’s consideration was if the government could claim exemption from producing all the orders passed under Section 144, CrPC, and if imposition of the restrictions was valid. The directions given and the legal position stated in the order are as follows:

- Restrictions be based on the concept of proportionality: This concept has to be applied to an order passed under Section 144, CrPC, said the Court. The magistrate should balance the rights of citizens and the restrictions he is planning to impose and apply the least invasive measure.

- Publication of orders: All orders under Section 144 must be published and be open to being challenged before the Court. The state or competent authorities will be responsible for doing the same.

- Subject to judicial review: The orders will also be subject to judicial review. To enable judicial scrutiny, all important and material facts should be stated in the order.

- Order in cases of apprehension of danger: While an order can be passed in case of danger and apprehension, in the latter case the danger should be in nature of an “emergency” and the order should be for preventing obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed. Therefore, power under Section 144 is both remedial and preventive.

- No suppression of speech and expression of opinion: The right to speech and expression forms the basis of a democracy. Orders under Section 144 cannot be used to suppress legitimate expression of opinion or exercise of democratic rights.

In short, the apex court expects the government to emphasise proportionality and reasonableness. Removing the cloak of secrecy could help in reducing the number of arbitrary orders and shutdowns. This judgment can be seen as a call for further action and a ray of hope as the Court has attempted to protect civil liberties along with laying down guidelines for the future.

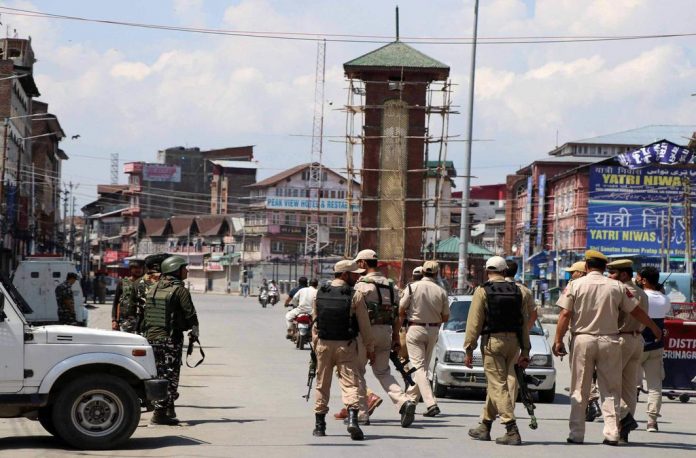

Lead pic: The SC noted the imposition of Section 144 in J&K and said the law needed to be justified/Photo: UNI