Above: Lawyers and litigants discussing cases at a Gurgaon district court/Photo: Anil Shakya

In a move that could increase the number of judges in high courts and reduce pendency, the apex court has ruled that retired judicial officers can be appointed as judges in these courts

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

On February 23, a Supreme Court bench of Justices AK Sikri and Ashok Bhushan ruled that retired judicial officers can be appointed as judges of any high court under Article 217(2)(a) of the Constitution. The verdict also said that additional judges can be appointed to high courts provided their tenure is less than two years and the appointment is done in conformity with provisions laid down in Article 224 of the Constitution.

The verdict was delivered against a petition that challenged the appointment of two retired judicial officers—Virendra Kumar Mathur and Ram Chandra Singh Jhala—as additional judges of the Rajasthan High Court on May 12, 2017.

The verdict can be seen as a possible remedy for filling up vacancies of judges in various high courts, thereby expediting the tardy pace at which cases are disposed of by these courts.

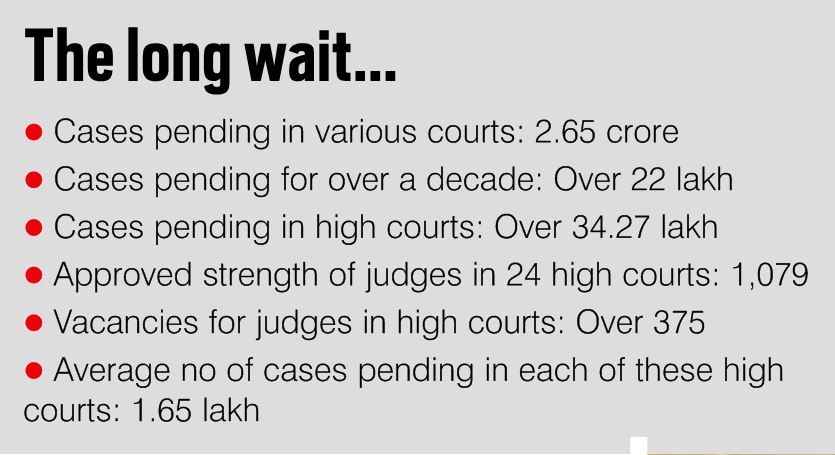

At a time when an average of 1.65 lakh cases are pending before 24 high courts, this verdict, which appears to be a definitive step towards reducing pendency, should have created a buzz.

So why did it not?

Justice AP Shah, former chief justice of the Delhi High Court, explained to India Legal: “Appointment of judicial officers as additional judges in high courts, particularly when the burden of pending cases increases, is nothing new. The Constitution, through Article 224, specifically provides for appointment of additional judges to tackle arrears in high courts. However, the apex court has now clarified that if due to bureaucratic delays, the appointment of a judicial officer as an additional judge is confirmed by the president after the said officer has retired but is still below 62 years of age, such an appointment will not be dismissed.”

The issue of bureaucratic delays holding up appointments of judges—permanent or additional—is, in fact, at the core of the Supreme Court verdict.

LONG DELAYED

Consider the facts of the petition that was filed before Justices Sikri and Bhushan. The recommendation to appoint Mathur and Jhala, then serving judicial officers, as additional judges of the Rajasthan High Court was made by the state’s acting chief justice on February 18, 2016. However, the long winding process that unfolds before a judge is actually appointed ensured that these two appointments were confirmed only on May 12, 2017—almost 15 months after they were recommended. The process includes endorsement of the recommended names by the chief minister, governor, the Supreme Court collegium, the ministry of law and justice and then, finally, the president.

By the time the appointments were confirmed, Mathur and Jhala had retired, a ground that led to the litigation as Article 224 provides for only serving judicial officers to be elevated as additional judges. Unfortunately, these delays also extend to filling vacancies for permanent judges.

The Supreme Court lamented this sorry state of affairs in its verdict, stating: “Enormous delay in appointment of Judges of the high courts not only frustrate the purpose and object for which Article 224 (1) was brought into the Constitution but belies the hope and trust of litigant…”

Recalling the top court’s earlier order in the Advocates-on-Record Association and Others v. Union of India case of 1993 with regard to filling vacancies for judges, the bench said: “The process of appointment must be initiated at least one month prior to the date of an anticipated vacancy to ensure that the post is filled up immediately… Unfortunately, it still remains a far cry.”

EXECUTIVE ROLE

The bench also noted the problems that such delays cause in dispensation of justice and fulfilling the primary objective of Article 224—clearing pendency. “Names are not forwarded by the High Court in time… even much after the vacancy has occurred. Once the names are forwarded, they remain pending at the Executive level for unduly long time, before they are sent to the Collegium of the Supreme Court… Even after the clearance of the names by the Collegiums, these remain pending at the level of the Executive. In the case of judicial officers of subordinate judiciary… this process of consuming so much time adversely affects their tenure,” Justices Sikri and Bhushan said in their verdict.

However, despite underlining the hurdles of red tapism in appointment of judges, the apex court resisted passing suo motu directives for addressing this malaise.

“It is a matter of common knowledge that most of the judicial officers get a chance for elevation when only few years’ service is left. When unduly long time is taken, even this lesser tenure gets further reduced… It is unjust that the fate of such persons remains in limbo for indefinite periods…

“It is in the interest of all stakeholders, including the judiciary, that definite timelines are drawn for each stage of the process, so that process of appointment is accomplished within a time bound manner. We need not say more,” the Court said.

NO TIME-FRAME

Legal experts—former judges and senior advocates—claim that the apex court could have gone a little further in its verdict. A former judge said on condition of anonymity: “Instead of limiting their judgment to just the case at hand, they could have possibly set a time-frame for clearing appointments of judges… this would have qualified their observations on the tardy appointment process and served the purpose of ensuring that high courts function as per the full capacity of their sanctioned strength of judges.”

With a staggering 2.65 crore cases pending in various courts, more than 22 lakh for a period of over a decade, according to the National Judicial Data Grid, delays in dispensing justice have been a challenge. And the situation has not improved despite successive chief justices, prime ministers and law ministers repeatedly vowing to correct the system. Statistics from the National Judicial Data Grid and law departments of various state governments show that high courts alone account for over 34.27 lakh pending cases.

It is, therefore, pertinent to ask whether the appointment of additional judges who have a tenure of less than two years is an effective mechanism to tackle pendency.

Justice Shah, also a former Law Commission chief, said: “I have always felt that the appointment of additional judges—especially those who have retired as judicial officers—makes little contribution in expediting disposal of cases. The only purpose that such appointments would serve is to give the chief justices of high courts the power to oblige certain individuals. It’s better to bring in younger judges who can serve longer and sensitise them to pendency.”

He added: “The problem with appointing retired judicial officers as judges is that the process is neither transparent nor does it ensure that on appointment, the individual will be able to dispose cases fast. What if laggard officers are promoted… There have been additional judges who have served for merely three to four months. When you have lakhs of cases pending in high courts, what major difference can an additional judge make in such a short span of time?”

VEXED PROBLEM

Former Chief Justice of India, Justice TS Thakur, who had been famously moved to tears at a public function in the presence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi while talking about the huge backlog of cases in various courts, welcomed the verdict. He told India Legal: “The issue of reducing pendency is a vexed one and one of the main tools of addressing it is by appointment of more judges, additional, ad hoc or permanent. When I was the chief justice, I had discussed the issue with chief ministers and chief justices of all states. We had decided that besides additional judges, we will also appoint retired judges who were over 62 years but were still sharp in their judicial acumen as ad hoc judges so that the judicature could benefit from their expertise. Unfortunately, the problem is that even if the judiciary expedites the process of appointing judges, the government sits on these files. It is the Executive that has to be more sensitive.”

Asked whether the Supreme Court should have set a time-frame for clearing names recommended for judgeship, Justice Thakur said: “The issue of a time-frame has already been dealt with in the Memorandum of Procedure (MoP). The government has unfortunately been sitting on the revised MoP for months. As long as the Executive doesn’t cooperate with the judiciary in reducing vacancies, cases will keep piling up and you will see more protests by lawyers and litigants like the recent ones in Calcutta and Karnataka High Courts.”

A majority of high courts is currently working with less than two-thirds their approved strength of judges. With over 375 vacancies for judges against the approved strength of 1,079 across the country’s 24 high courts, there is clearly an urgent need for the Executive to respond to the Supreme Court on the vexed issues related to MoP.

The Supreme Court has spoken. It is now for the Executive to do its part. In the absence of a firm resolve to reduce pendency, litigants will only get disenchanted with the judicatures, if they already aren’t.